Death of an Empire (31 page)

Read Death of an Empire Online

Authors: M. K. Hume

Thanking the gods that they had arrived in late spring and not during the virulence of the summer months, Myrddion mounted his new horse, a showy grey gelding that seemed weak in the hocks, and sought out Cleoxenes, who was preparing to depart in company with his bodyguard.

‘I’d like to thank you, my lord Cleoxenes, for all your efforts on my behalf. I’ve nothing to give you of any value, but if a Christian is not offended by the prayers of a pagan, I will beg the Mother to keep you safe until you reach the sanctuary of your home.’

For all his urbanity, Cleoxenes was embarrassed by the gesture of friendship. But he accepted Myrddion’s compliments in the spirit in which they were offered and promised to seek the healer out in Rome before he left to join his new master in Constantinople. Then the envoy fished a cloth-wrapped package out of his saddlebag.

‘This gift is for you, healer. I saw your eyes light up when I first mentioned Homer’s Odyssey. Unwrap it. Yes – it’s yours, and

without any qualification. Enjoy the writings of the master, although Homer reads a little better in the original Greek.’

Myrddion gazed down at the scroll cylinder in his hands. The extensive carving on the container indicated its worth and a quick glance at the Latin script showed it to be a beautiful example of the scribe’s art.

‘I read Greek, my lord,’ Myrddion answered automatically, and because his eyes were riveted on the scroll in his hands he missed Cleoxenes’s dumbfounded stare at his admission. ‘This gift is far too valuable. You have been my friend and my mentor, and those gifts are so great that I will never be able to return them. But this . . .? The Odyssey? I cannot accept such largesse from you.’

‘Oh, for the sake of all the saints, Myrddion! Just say a simple, polite thank you, and I shall have been repaid many times over. No! I won’t listen to another word.’

Then Cleoxenes dug his heels into the flanks of his horse and the beast leapt sideways in a nervous prance.

Once the envoy had ridden away, accompanied by his brawny guard, Myrddion felt a profound sense of loss. Cleoxenes had smoothed Myrddion’s path in a hundred different ways, but his careless friendship too had been much cherished, for never before had Myrddion had a true companion of his own class. It was not that Myrddion cared about birth, but that Cleoxenes had filled a void in the young man’s mind, and they had shared the easy camaraderie of intelligent, educated and curious men.

Noble forums, huge marble baths, a circus that made Myrddion’s head spin in its complexity and the multi-storeyed buildings of the subura were evidence of a culture so superior to anything the healer had known that he felt a pang to see derelict buildings falling into ruins. The city was angry with gangs of hollow-eyed, half-starved unemployed who frequented the wine shops and roved the streets in search of vulnerable prey. Fear of the swords

and daggers carried by Cadoc and Finn was all that protected the healers from robbery, murder and rape.

‘Ostia is a cesspit that is still beautiful on the surface, but rotten at the core,’ Myrddion told his apprentices. ‘I long for clean air and the green of the countryside. Let’s blow the foul stench of this place out of our lungs.’

And so Ostia began to recede into the distance.

Although the afternoon was advanced, the small party shunned the nearer inns, preferring to push forward along the well-constructed road until the city was only a memory. As darkness fell, and the buildings of Ostia started to thin out into isolated pockets that were linked by plots of rubbish or desultory, half-hearted agriculture, Myrddion breathed freely at last. He discovered that he preferred the blood-soaked battlefield to this world that seemed to be rotting from gangrene of the spirit, even as it lived.

‘If Ostia is a corpse not yet buried, what then will we find in Rome? What can I learn in an Empire that is falling to pieces as I watch?’

Cadoc turned his head in the darkness, and Myrddion realised he had voiced his despair. Wisely, both Cadoc and Finn maintained their silence.

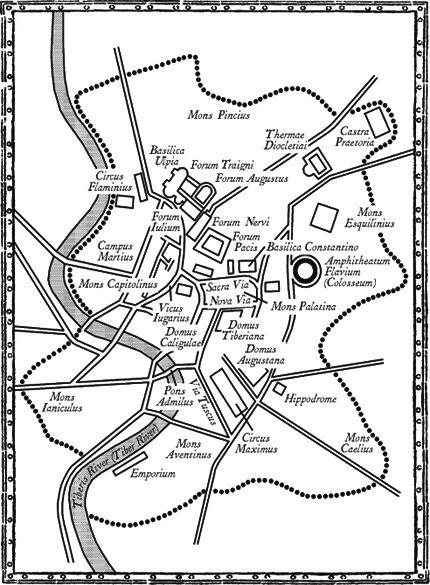

MYRDDION’S CHART OF ROME AND ITS ENVIRONS

THE CITY AND THE SUBURA

The healers spent the night sheltering in a stand of olive trees. Myrddion scented danger on the night wind, as pungent as corpse smoke and as sour as bad wine. Out of patience with his instincts, he told himself that months of travel had left him jumpy and filled with the anxiety that men feel when they venture into strange places. Dawn found the companions awake and the air was ripe with reheated fish stew, the sharp scent of crushed olive leaves and a cinnamon sweetness that Myrddion didn’t recognise. Even at this early time of day, the air had a stultifying heaviness, as if fine dust hung constantly in a hot haze.

Daylight revealed bare, exposed countryside that seemed too spent to bear life. Even the old olive trees seemed tired and malnourished. An early gust of wind blew little dust devils into being in a field of dispirited green shoots that were struggling to survive.

‘What’s wrong with this land?’ Myrddion asked Finn, whose family had been farmers for generations. The Celt went down on his haunches and took a handful of pale soil in his fist. He squeezed it, but the earth refused to knit and began to sift through his fingers like sand.

‘It’s played out, master. All the goodness in it has been sucked

away over years and years of constant cultivation. The soil must be replenished if it is to bear. Every few years, my father would grow a crop simply to plough it back into the ground to provide nourishment for our fields. Then he would permit the earth to rest for a season. If a farmer becomes too greedy, or too needy, he will kill the soil by making it bear beyond its strength.’

Myrddion sighed. ‘Veterans from the Roman legions have been given small plots of land all over Italia for hundreds of years as a reward for their service to the Empire. It’s sad to see this once-fertile land destroyed by ignorance. Men trained for fighting usually know nothing of farming.’

‘Aye, master. It’s little wonder that Rome now depends on grain from its Empire – what’s left of it.’

‘It’s time for us to leave, Finn. At speed! We still have some rations remaining that will be valuable, if the quality of this crop is anything to judge by. Rome is close, so we shall soon see what the Empire has become.’

In the tiring journey that followed, though he marvelled at the imaginative engineering that created the roads, complete with channels to drain water away from the surface, Myrddion also saw how damaged the landscape had become. While olive trees still survived on the slopes of the low hills, deep ravines of erosion scoured the flatlands and exposed the sour subsoil. Goats devoured any tender shoots that managed to burst through the weary soil, and their hooves trampled the dry ground into dust for the wind to blow away.

Any farmers whom the healers met on the journey were tired, bowed at the shoulders and defeated by years of struggle. One by one, the smaller farms had been devoured by affluent landholders, so that the original owners toiled for coppers in order to enrich absentee noblemen. Resentment shone out of the eyes of the peasantry, as their landlords demanded more and more income

from depleted land they never saw. The hands that had once carried swords for the honour and glory of Rome clenched and unclenched in anger at the sight of the healers, for although the travellers were ragged they rode horses, and were therefore wealthy. No one sought treatment. No one spoke.

For the first time since they had left the Catalaunian Plain, the small party was forced to guard the horses and their wagons as they slept that night by the side of the road. The men rested in shifts so that the campsite could be protected in the event of an attack, and were fearful of lighting a fire lest they be discovered by footpads. Myrddion now understood why Cleoxenes travelled to Rome with well-armed bodyguards.

‘Italia is far more dangerous than Cymru, and the population is hostile and angry,’ he told Finn on the last morning of their journey, although his companion was obviously aware of their peril. Myrddion had been struggling to understand the bitterness in the farmers’ eyes as they travelled through this dangerous, depleted land. ‘The countryside seethes with resentment, and we can only hope that Rome must be better than this.’

Late on the second day they reached the outskirts of Rome itself, and made camp so they could enter the city during the relative safety of daylight.

That night, the stars were harder to find in the dark night sky. The city generated its own light through cooking fires, oil lamps beyond counting and flares lit in the streets to guide the throngs that prowled the thoroughfares throughout the night hours. For as far as the companions’ eyes could see, little flares of light outlined unshuttered windows or revealed half-seen shadows of walls, columns and what appeared to be multi-storeyed buildings.

Sound carried to them on the night wind, too, as if the city was growling deep in its throat. Myrddion knew the ugly hum was composed of hundreds of thousands of voices, crying, groaning,

talking, lovemaking or dying, as well as the barking of dogs, the noise of cattle being prepared for the slaughter yards and the cries of exotic animals in the pens below the arenas.

After an hour of listening to the heartbeat of the great city Myrddion fell asleep, to dream of dead earth that offered up the bones of countless victims who had been sacrificed in the name of Rome for over a thousand years. In his dream, the bones poisoned whatever they touched, until the river itself became an acidic wasteland of bloated corpses. Skulls smiled at him with shattered teeth and lifted bony fingers that begged for healing.

When the night horrors finally released him, Myrddion awoke with the taste of ashes in his mouth and salty tears on his lips.

In the early morning light, Rome was stranger and more exotic than Myrddion could ever have imagined. For much of the previous day, the Roman road had hugged the Tiber, with all its attendant smells, and now the healers approached the city from the south with mingled feelings of excitement and trepidation.

The going was slow, for the road was crowded with vehicles of every kind, farmers afoot carrying baskets of goods for the markets, horsemen and peasants riding on spavined donkeys. Myrddion’s wagons could only crawl along as the loud, discordant throng shouted, cursed and forced their way into the city.

Ahead of them, the travellers could see a small cavalcade approaching. A noble personage reclining in a huge, gilded divan, complete with gauzy curtains for privacy, was borne on the shoulders of eight coal-black Nubian slaves. Guards accompanied the little procession, and Myrddion judged by their fine clothing and luxurious accoutrements that the traveller was a person of considerable prestige. The Celts had never seen such opulence and stood gape-mouthed at the ostentatious display until one of the guards slashed at the lead horse of their first wagon and ordered them out of the way in curt, crude Latin. As the Nubians trotted

past carrying their heavy load with scarcely any sign of sweat or effort, the companions were struck anew by the lack of common courtesy and the automatic assumption of preference shown by such men as the one who lounged within the drawn curtains.

‘No wonder the farmers are angry, if great wealth is thrust under their noses by the aristocracy for whom they labour so hard for so little profit,’ Myrddion murmured, affronted despite his acceptance that the healers had no status in this city.

‘I, for one, would like to tip that bag of wind onto the roadway on his fat arse,’ Cadoc replied with unusual venom. The warrior rarely became upset at the foibles of the aristocracy, but in this instance he was thoroughly disgusted by the indifference displayed by master and slaves alike to the needs of anyone but themselves.

‘How can you tell that he, she or it has a fat arse? The traveller is completely invisible in case the peasantry might contaminate him by looking at him. But I know how you feel, my friend. Such arrogance! Lady Flavia is a rank amateur in matters of pretension.’

What this trivial incident confirmed for Myrddion was the great gulf that existed between the rich and the poor. The Celts, the Saxons, the Franks and even the Hungvari had their wealthy citizens who arrogantly flaunted their status over the peasantry, but within those lands the farmers and the poor had some recourse to justice through their lords. In Rome, the poor had nothing, while the nobles owned everything, even the souls of their slaves. Above all, rich or poor, to be Roman was everything. As outlanders and non-Romans, the healers were less than nothing.

The visitor’s first impression of the city was its sheer size, a vastness that battered the healers’ concepts of the needs of such a huge populace. Rome was huge, enclosing and covering the seven hills of universal fame, shining in the noonday light with marble of every colour and size. The Circus Maximus was large enough to

contain a chariot racecourse and more. The Palatine rose above it, brilliant with the Hippodrome, the Domus Augustana, the smaller Domus Tiberiana and the infamous Domus Caligulae. Temples glittered with forecourts of shimmering white marble columns, while palaces and mansions raised their careless, ordered heads towards a brazen sky.