Death of a Duchess

Chapter One: ‘So the dog barked, after all’

Chapter Two: ‘They’re not her hands’

Chapter Three: ‘Whose Colours?’

Chapter Four: Dark as the grave

Chapter Five: ‘It was missing’

Chapter Six: ‘

Did

I kill the Duchess?’

Chapter Seven: ‘My mistress wishes to sell this ring’

Chapter Eight: ‘She owed me...’

Chapter Nine: ‘I release you of your task’

Chapter Ten: ‘The omens are excellent’

Chapter Eleven: ‘Call me madam’

Chapter Twelve: No time to waste

Chapter Thirteen: ‘Cousin Caterina’

Chapter Fourteen: ‘You’ve lost your hair!’

Chapter Fifteen: ‘Like grasping a cloud’

Chapter Sixteen: ‘What kind of money?’

Chapter Seventeen: ‘A friend to true love’

Chapter Eighteen: ‘Escape, would you?’

Chapter Nineteen: ‘You want my father to commit treason?’

Chapter Twenty: ‘There is her murderer!’

Chapter Twenty-One: ‘My son, what have you done?’

Chapter Twenty-Two: After the Devil, the Dead Man

Chapter Twenty-Three: ‘No one is what they seem’

Chapter Twenty-Four: The promise of Venus

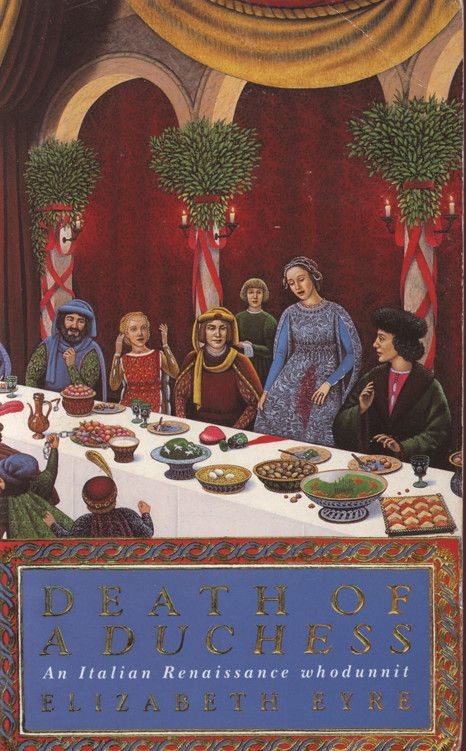

When a deadly feud between two wealthy families threatens the life and rule of the Duke of Rocca, he decrees a marriage between them. But this is a Romeo who despises his Juliet, a Juliet who runs away from her Romeo.

The girl is kidnapped — or has she run away? — and the Duke employs one Sigismondo, the man from nowhere, quiet, enigmatic and observant, to find her. Sigismondo sees a number of things that don’t add up: a dead dog, a servant lying in the fire, but finds little enlightenment. He is present at the fatal banquet which ends in fireworks and the murder of the Duchess of Rocca in circumstances which point to the son of the feuding family.

Whilst the boy awaits the scaffold, Sigismondo sets out to unravel the mystery, foil a conspiracy — and reveal the murderer lurking behind a courtly mask...

DEATH OF A DUCHESS is set in the danger of a time which feeds on poison, the days of the Medici and the Borgias, but spiced with humour as Sigismondo, a man as good with his brains as he is with an axe, stalks through, followed by the shrewd half-wit, Benno, and his little one-eared dog.

‘So the dog barked, after all’

‘From this very bed she was snatched!’

The Lord Jacopo di Torre’s long sleeve followed his dramatic gesture and swept a scent bottle from the bedside chest. The Duke’s emissary, with an agility unexpected in one of his strong build, caught it, and stood turning it as if to admire the carved onyx and gold. Jacopo waited for a comment about the bed, whose sheets had been wrenched back, pillows tossed abroad, with every sign of a violent struggle. There could be no doubt that he was right. This had been the very bed.

‘You heard nothing?’ asked the deep foreign voice.

Jacopo’s hands, waiting for the next gesture, balled themselves and struck at his forehead. ‘Nothing. Dear Mother of God, I sleep like the dead!’

The emissary’s dark eyes genially surveyed the door full of servants who gaped and manoeuvred for a better view. ‘And no one else heard anything?’

Heads were shaken. An elderly woman in an extinguishing head kerchief kept up a low wail amid her linen. Jacopo glanced at her with irritation. ‘Even my sister slept. No one heard anything. In this whole household, every living soul slept!’

Not one of the servants seemed ready to oppose this. To sleep soundly at a legitimate hour was, after all, the mark not of laziness but of exhaustion brought on by virtuous toil.

The emissary replaced the scent bottle, pushed askew with a finger the other objects on the chest — a pair of silver tweezers, an ivory comb, a Book of Hours in a red velvet cover, a carved ivory mirror with a bronze nymph for handle — and picked up the silver posset cup, removed the lid, and sniffed at it. The servants followed every action with the acute interest they would have given to a mime.

‘You think she was drugged?’ Jacopo pounced on the idea. ‘Was that why we did not hear her?’ He seemed relieved that his daughter had not suffered the frustration of crying out unheard. ‘Ah. No. No one in this household...’ Indignant agreement from the servants drowned out what promised to be an inconclusive remark in any case. A drug must be introduced by some hostile hand.

The heavy shoulders shrugged, and the emissary indicated, with a movement more economical than Jacopo’s, the bed. A drugged girl might scarcely be capable of putting up such a fight. Brocade bed-curtains, of green and gold, sagged at the far side, ripped from the half tester.

‘The dogs slept too?’

Some agitation started among the servants, faces turned in question. ‘In the yard... other side of the house... her little dog—’

The emissary caught the words. ‘Her little dog?’

‘My daughter’s dog.’ Jacopo gazed about, as though it should have the manners to come out and apologise. ‘It must have run away. Terrified.’

‘Too terrified to bark.’ The emissary nodded as if it were axiomatic that a wise dog would stifle noise for fear of harm. He asked no further about yard dogs that might be expected to sense an intruder where the righteously slumbering household had not. ‘How did they get in?’

Jacopo chivvied him to the window, with darting motions of the hands that failed actually to touch the fine black leather of the man’s jerkin. The emissary duly examined the forced shutters, and stepped out onto the small loggia. He had a habit, which Jacopo found as irritating as his sister’s wailing, of humming deep in his chest when he was shown anything. It was not a tune, but a sound like a satisfied bee. It conveyed the disturbing impression that all he saw was what he expected to see. He leant over the stone balustrade and, narrowing his eyes, surveyed the ground below. Jacopo snapped, ‘The roof. They came over the

roof

.’

At his leisure, the large man reversed, sat on the balustrade and, with a hand round the Ionic pillar, leant out to look along the roof, at the ridged tiles and the houseleeks.

‘It is possible, just possible, to leap onto our roof from the next house. It is the only way they could have come. My walls are high, the gates to the courtyard are of course barred at night.’

‘But they did not leave this way, carrying the girl.’

Certainly the roof did not look negotiable for anyone laden with a struggling girl, and even less so would be the leap to the neighbouring tiles.

‘Of course not. Of course not. They left by a side door that gives on the street. A servant found it unbarred this morning.’

‘Who found it?’

A man thrust forward, apple-red with importance and, taking permission from a wave of his master’s hand, spoke, while the others nodded in confirmation of a tale no longer fresh to them.

‘It being my duty to fetch wood to the kitchens from the yard store of a morning, and going along past this door I saw the bar was down, which it never is, us not using that door, and then I saw...’ he paused, clearly expecting to be asked what it was he saw. As the emissary watched him in silence, he hurried on with his drama. ‘I saw — this!’

He produced what had been crumpled between his hands, a piece of torn cloth, yellow and red. Jacopo snatched it from him and held it out, quivering, to the emissary, close enough for him to sniff it had he so required.

‘You see! You see?’

The emissary would have had some difficulty not seeing the cloth thrust at his face, but he did not stir.

‘You see? I told the Duke I had proof. It is the noble, the esteemed Lord Ugo Bandini who has abducted my daughter! These are his colours!’

The emissary took the piece of cloth and pulled it about, inspecting it idly. He hummed.

‘Where was this found?’

‘Caught on a nail, sir, just by the door.’

‘The villain must be brought to justice!’ Jacopo twitched the cloth from the emissary’s fingers. His indignation had a respectful echo, a groundswell of agreement from the servants. The stranger’s eyes lifted to examine them again.

‘Is your daughter, only, missing?’

That

only

made Jacopo draw himself up. ‘Her maid, it is true, is also gone. She slept here, of course. A Circassian slave.’ The straw mattress against the wall was indicated by a slight movement of the hand. ‘They must have taken her for fear she would discover their appearance to us.’

‘She made no noise either.’

Jacopo’s eyes stared from widened circles of white. ‘Gagged! They were both, then, gagged! Snatched from their beds, carried off from under my roof. Who but Ugo Bandini would treat the Duke’s command with such contumely? He has done this to prevent my daughter’s marriage to his wretched son. I freely own—’ he flung out his arms, as one revealing even his faults — ‘that I want the marriage no more than he does, but I am obedient to the Duke. The Duke must force Ugo Bandini to confess the crime. Who but he would perpetrate such a deed?’

‘Bandits, for a ransom?’

‘

Bandits!

’ Jacopo’s voice cracked; then he seemed to consider this idea for the first time and not to like it. The servants whispered, arguing, while the aunt renewed her moans and the emissary waited, head on one side.

‘You think it unlikely, my lord. Yet it is said that you are the richest man in the city. Except for the Lord Ugo.’

At the aspersion, Jacopo broke out once more, brandishing the coloured cloth. ‘Bandits?

He

is the bandit. This is my proof! My motherless daughter is in his hands. Let him look to her safety! The Duke must order that she be restored!’

‘Excuse me, my lord.’ The emissary extended a hand, brown and powerful, took the piece of red and yellow cloth and stowed it in the bosom of his jerkin. ‘As you say, it is a witness. And now,’ he bowed, ‘may I see the door which was found open?’

He saw it, after scrutinising the wall to the side of the stairs on the way down (a fresco obliterated by the grease of years of passage) and the nail which had held the cloth. He saw even the street outside the door, a side lane, narrow and dark, with no inhabitant but an old man walking away with fragile slowness in the rutted mud, and a cur tormenting his heels. The emissary was minutely interested in a pile of horse dung near the door, and by the information, delivered with emphasis and repetition and by several voices, that the nightsoil of the household was conveyed away every week on this very day to the master’s farm in the country, and by a dungcart left in this very lane the night before to be collected this very morning. Farm men brought the clean cart, hitched the horse to the full one, and took it away. The clean cart, the emissary was informed, that would prove the truth of what they told him, stood m the kitchen yard just round the corner. It had been dragged in there the moment the house was awake, as the master liked, they added, discovering Jacopo’s presence among them and bobbing their heads zealously.

Jacopo, seeing that the Duke’s emissary was not content with observing horse dung in the lane but was now strolling up the lane towards the corner, the street, and the yard gates, parted the servants after the manner of Moses with the Red Sea and bustled into the lane, grabbing up his velvet skirts and giving the dung all the room it needed.

‘You think they went this way?’

‘All possibilities are to be examined, my lord. The Duke was insistent.’

Jacopo’s mouth, opened perhaps for a protest, snapped shut. He adapted his step to the emissary’s. A cat, eating something fascinating in the dust, lifted its head, sped across the lane and vanished into a dark doorway whence came a sound of clattering pots and yawning.

Round the corner they found the tall gates of the kitchen courtyard open to the street beneath the brick arch of the wall, and a trio of burly men delivering jars of oil from a handcart. A smallish, vacant-looking man, not in livery but comprehensively clad in grime, stood watching, cradling and fondling a little woolly white dog in his arms. Jacopo speeded up and approached this man with pointing finger.

‘Where did you get him? Where?’

The man looked up in innocent surprise, his mouth falling open with the ease of long practice. There was straw and dust in his black beard.

‘It’s m’lady’s dog. Biondello.’

‘I know what it is. Where did you

find

it?’

The emissary, now at Jacopo’s side, extended a finger to scratch the top of the dog’s head, and withdrew it, nodding as though someone had made a useful statement.

‘Where did you find him?’ Jacopo spoke as one would address a large crowd in, say, an arena, and everyone except the small man and the emissary jumped. The small man did not jump because he was being shaken by Jacopo.

‘Foot of the wail, out there.’ He nodded at the street. He showed no resentment at the shaking and perhaps was grateful for the stimulus. Jacopo was the one now stunned and speechless.