Death: A Life (3 page)

As well as being veterans of the same campaign, these guardians of mine had a tremendous respect for Father. It was a respect that I could never entirely understand.

“Your father was the brightest and best of us all,” I remember Sargatanas, the brigadier general of Hell, recounting. “He was forever putting down the angel Gabriel. Oh that Gabriel, no one liked him. Always a little too keen, if you know what I mean. Anyway, your father was the one who thought we should try to instigate an Angelic Workers Republic and replace God with a Central Seraphic Council composed of an amoral proletariat and auxiliary cherub brigade. Ah, such foresight! We owe him everything.”

“But you’ve all been damned for eternity in the fiery pits,” I couldn’t help but say.

“Very true, young Death, very true,” croaked Sargatanas. “But, as your father says, ‘Better to rule in Hell than to serve in Heaven.’”

“But surely you don’t like eternal damnation?”

“Why of course I do, my boy!” he replied, sucking in his chest. “There’s nothing finer than awakening to the dreadful din of hissing, followed by a dip in a pool of burning magma and a good exfoliation in the scalding steam vents, before lying down beneath the fiery sky content in the knowledge that you’re subject of the eternal ire of the All-Powerful.”

“But didn’t you have feathery wings in Heaven,” I protested, “not these horrid scaly ones? Wasn’t that better?”

“Feathers!” spluttered Sargatanas. “Feathers are for the birds, my boy. Flaking, peeling, scale-ridden wings, now that’s what real beings wear. I’ll tell you a secret,” he said, and drew me closer. “The eternal pain at having known Paradise and lost it is priceless. I wouldn’t swap it for anything.”

“Really?” I said. “You really wouldn’t want to be back in Heaven?”

“Never. Not without my pool of burning magma.”

“But if you wanted pools of burning magma in Heaven, couldn’t you get them?” I asked.

“Oh no,” said Sargatanas, rubbing his chins. “Well, maybe. But not like the magma down here.”

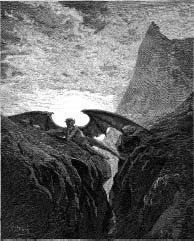

I had always been a bit confused about the devils. They were always crying out in pain and anguish, yet when you tried to console them they always said they wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. I remember Sargatanas taking me to the highest tower in the Palace, as the gorgons and hydras screeched below. He proudly swept a claw over the hellish landscape, which was, as usual, completely obscured by a thick, choking fog. “To think,” he said, “without your father we wouldn’t have all this.”

The Palace of Pandemonium: “Disorder! Disorder!”

Being Satan’s child did have its perks. I could torment any of the Dukes of Hell without so much as a smack. They would just waggle their talons at me as I clawed their faces and look at one another and say, “Just like his father.” I remember one day Beelzebub, whom I liked very much for the swarm of flies that perpetually surrounded him, took me to one side and said that great things were expected of me. At the time I hadn’t a clue what he meant.

As I said, I wasn’t an easy child. I tortured my poor mother. Literally. With fire and hot irons, every night. And in Hell it was always night. But what did I know? I was young, dumb, and full of the emptiness of the void. Looking back on it all, I realize that the person I really blamed was Father. All the time I was drilling into Mother’s skull I was wondering what had happened to him. Where was he? Why didn’t he write?

When I wasn’t beating Mother, or setting her aflame, or stretching her out on a rack, or running her through with spikes, or throwing her onto sharp rocks, or hammering her head flat, I helped her guard the Gates of Hell. Mother insisted on keeping the gates sparklingly clean. This was harder than you might imagine since they were entirely constructed of splintered bone and cartilage. I never got along with the gates. The doorknob screamed at me whenever I touched it, and the hinges were always making unsavory remarks about my skin. Mother never told me why she had decided to start guarding them. “I just did,” she’d say, as her long forked tongue licked the gates free of soot, sending the keyhole into moaning ecstasies.

I remember watching her at work and marveling at her certainty. She was so thorough and absorbed in what she was doing. I suppose everyone finds their true calling in the end, but at the time I didn’t know what I was meant to be accomplishing. On some days I’d pretend I was a demon. I had made myself a pair of horns and a tail out of the horns and tail of a smaller, weaker fiend, but the real demons would see through my disguise and tease me, saying that I was a good-for-everything, always-do-well. Other times I’d pretend I was the embodiment of some moral transgression, like Rape or Murder, but deep down I knew I wasn’t, and Mother would tell me to stop being silly and to pass the duster.

Infernal devils being what they are, there was an unending line of imps and demons trying to sneak through the gates. But Mother was impervious to both threats and flattery. I remember when Buriel, one of the many Princes of Hell, said he needed to pop out for a minute as he’d forgotten his keys somewhere in the void. Mother ate him. Or when that charming roué, Asmodeus, put a long tentacle across her shoulder and tried to woo her with his piscine charms. Mother ate him too.

Asmodeus: Devil of Many Parts, Few of Them Matching.

Yes, we heard the whole gamut of excuses: how they had fallen by mistake, or taken the wrong turn and ended up in Hell by accident. In the case of the strangely delicate devil known as Reginald, I was almost inclined to believe him.

Reginald always wore a tunic that shone brilliantly despite the soot and dirt that clung to it. His face carried a permanent look of consternation. Every day he would appear at the gates and repeat his story—it never varied. He had arrived at the Battle of Heaven late, he explained, and had rushed headlong to fight on the side of good when a strap on his sandal had come loose and he had tripped and fallen headlong into Hell. He even had his damaged sandal to prove it. He thus insisted that he was not a fallen angel, but rather an angel who had fallen. It was an interesting semantic distinction.

“I assure you, madam,” I remember him saying to Mother, “I am telling the truth.” This always caused the surrounding devils, who always turned out in great numbers whenever Reginald tried to argue his way out, to burst into fits of laughter.

“But no one tells the truth in Hell, Reginald,” said Mother, who I think was secretly quite fond of Reginald.

“But I’m not a devil!” said Reginald, his voice rising in pitch. “Look at my wings.” Reginald’s wings, although in need of a good comb, seemed distinctly more feathery than the usual scaly fare.

“Ah, Reginald,” said my mother, “but no one in Hell looks like they should. We are all dissemblers here.”

“Oh, but this is ridiculous!” said Reginald. “Look, I’ve got a halo! I’m a bloody angel!” It was true that hovering over his head was a ring of effervescent light, albeit one that had seen better days and now spun atop Reginald’s head on a slightly rakish orbit.

“Reginald, Reginald, Reginald,” said my mother, her eyes gleaming, “are you saying the Creator made a mistake?”

“Well…I…”

“Are you saying the Lord God Almighty, in all His infinite wisdom, somehow made a blunder?”

“Well, I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a mistake…” spluttered Reginald.

“What kind of an angel, Reginald,” said Mother, gleefully sensing the endgame approaching, “would doubt the infallibility of the Creator? Surely that’s the kind of thing that could land a person in Hell, isn’t it, Reginald?”

“But…but…,” said Reginald.

“Nice try, Reggie dear,” said my mother soothingly, putting an arm across Reginald’s slumping shoulders, “but not today. Why don’t you come back tomorrow and we can talk this over again.”

Arguments with Reginald always seemed to end this way, and to the jeers of the onlooking devils, he would trudge back to his gleaming cave, scrape off the obscene graffiti that had invariably appeared during his brief absence, and pluck sadly at a rather battered and out-of-tune harp. I often visited Reginald there and talked to him about Heaven. Unlike all the other devils he really seemed to want to return.

“I tell you, Master Death, I would do anything to get back,” said Reginald. “Anything good that is, of course. Of late I’ve been tempted to try and steal your mother’s keys. A little voice in my head is always telling me that only then would I be able to go back to Heaven.”

“That would be Uncle Puruel,” I explained. “He’s very small but quite persuasive.” I heard Puruel shout a high-pitched greeting to me from out of Reginald’s ear.

I felt a strange affinity for Reginald, because I too didn’t quite fit in. Neither demon nor god, my self-esteem was shot. I just wanted to belong, to be approved of. But while the other devils were always plotting or torturing or cackling, I preferred doing nothing. Nothing at all. I would sit far away from the burning flames, in the Bottomless Pit, or the Endless Abyss, or the Black Gulf, and there I would feel settled and comfortable. As the Darkness rushed around me I didn’t talk, or breathe, or think. I just reveled in the eternal blackness and in the deep silence that persists forever. The older I grew—the closer I came to being a fully grown-up unchanging perpetual—the more I liked feeling the edge of Creation just slipping by.

I remember it had been a quiet day at the Gates of Hell. Reginald had come and gone, a note stuck to his back reading

TORTURE ME,

when suddenly an overwhelming aura of evil swept toward us. There was the flap of mighty wings, the succubae vanished, and Father appeared in front of us. He was wearing fleur-de-lis velvet slippers the size of aircraft carriers, an immense dark purple dressing gown with three interlinked sixes embroidered tastefully on the chest, and a vast black towel hung over his shoulders. He had just come back from bathing in a volcano.

“Hello, Sin,” he said to Mother, a smile lingering at his mouth.

In Hell, Silence Is Leaden.

“Hello, husband. I mean, Father. I mean…” Mother giggled. She was always thrown into a blushing confusion by Father’s presence.

“Just call me Satan, darling,” he said, casually looking around him.

“But it sounds so awkward,” said Mother, girlish now, smiling coquettishly and twirling her snakes around a finger.

“Would you mind letting me out for a moment,” said Father, raking a long talon across Mother’s cheek and motioning toward the gates.

“Well…I…,” said Mother, torn between sexual attraction, filial respect, and duty.