Death: A Life (14 page)

“Grievous the Shouts of the Many Men Killed, / by the Snapping Beak of the Beast Duck-Billed.”—Ovid

Attacks on giraffes, whom the Heroes thought were half-leopard and half-camel, and on leopards, which were said to be half-panther and half-lion, soon followed. When it was whispered that many of the Heroes themselves were demigods, the Age of Heroes ended in a wave of bloody internal purges.

I could hardly claim to be upset by the unceasing slaughter. The Darkness happily accepted all regardless of race, creed, or plausibility, but the new gods were forever interfering in my business, and that I could not abide. At the Battle of Troy the gods were diving in and out of the action like lifeguards at a whirlpool, saving each of their favorite warriors and whisking them to safety. The goddess Athena was always interrupting me, claiming that this soldier or that soldier was her personal favorite and could I make an exception and not send him into the Darkness. The

Book of Endings

swiftly became filled with strikethroughs and erasures.

I didn’t like this. Each morning I would carefully mark out the soon-to-be-dead by region and then work out how long each area would take me. The meddling of the gods threw my calculations off completely. By now I considered myself something of a perfectionist. I reckoned that if a job had to be done, it was better that it be done quickly, and efficiently, than in a haphazard manner. Neither was I biased in my work. Be you prince or pauper, porpoise or penguin, I treated everyone much the same. I saw no difference between the brief lives of worms, or the long spans of turtles, the death of babies and the dying of nonagenarians. But now, on the battlefields of the Mediterranean, I could tell that those who weren’t the gods’ favorites were starting to get suspicious of my impartiality. After all, the buck stopped with me.

“Where’s Achilles?” a dead soul would say.

“Standing over there,” I’d say.

“Are you sure he didn’t die?”

“Quite sure.”

“But he was in the same chariot as me, you know?”

“Yes.”

“And the chariot did go over the edge of a cliff.”

“Yes.”

“Then how did he survive?” he’d ask, pointing to the mangled wreckage of the chariot and his own dismembered body.

“Luck?” I’d venture, and the eyes of the dead soul would narrow suspiciously as the Darkness consumed him.

Furthermore, the gods were always competing with one another. They would often wait for me next to the souls of dead warriors whom they had drowned in a storm or had stabbed in battle and insist that they be given the credit for the kill.

“Mark it down for me, Death,” I recall Aphrodite telling me as I hurried through a village decimated by an earthquake. “That’ll show that tart Hera. What’s the score at present?”

“Well, ma’am,” I said, for I always thought it wise to stay on the good side of any divine presence, “that places you at eighty-four thousand and ninety-six.”

“And Hera?”

“Still ahead of you, ma’am. One hundred and sixty-four thousand.”

“Damn. Any big disasters planned for the future?”

I dipped into the

Book.

“Well, there is a volcanic eruption at Vesuvius scheduled for next month.”

“How many?”

“Over two thousand.”

“Any chance I can help out? You know, divinely freeze them to the spot, or turn them all into statues or something?”

“Why would you do that?”

“For failing to sacrifice to me?”

“Have they forgotten to sacrifice to you?” I asked.

“Oh no. No, not at all. They’re very good with their sacrifices at Pompeii. Always on time, always very plump cattle.”

“So why do you want to help kill them?”

“Two thousand could really put me back in the game, Death. Don’t you understand?”

That’s the problem of having a pantheon of all-powerful beings; everyone wants to show that they’re more all-powerful than the other.

“I think the lava and fumes will do just fine, thanks,” I said.

“How about if my wrath just causes the volcano to erupt?”

“I’m afraid you used your wrath last week on that landslide in Thebes.”

“Oh, but that wasn’t really my wrath, more my irritation. And, besides, it only killed twenty or thirty.”

“Twenty or thirty members of the Theban royal family, who were, you may recall, beloved of Poseidon.”

“Oh yes. He’ll be sinking my ships again, I’m sure. Still, is there no way I can be worked into the Vesuvius eruption?”

When a goddess bats her eyelashes at you, it is an unsettling experience. I buried my head in the

Book.

“Well, I suppose I could write off a few as having suffered just vengeance after having cursed your name, but I must inform you that the majority of the deaths are already allocated to Apollo.”

“What!” squawked Aphrodite. “How so?”

“Well, some of their young defaced his temple the other day. They said they didn’t believe in him.”

“Good for them!” said Aphrodite. “Sometimes I don’t believe him either.”

“In him,” I corrected. “They said they didn’t believe

in

him.”

“Oh,” said Aphrodite. “Well, okay then.”

Not believing in a god was a very serious affair, especially with faith now being spread so thinly across the massive pantheon. Without faith in their existence, gods slowly shrank and disappeared.

The same was true for God Himself, but He had circumvented this problem by inhabiting everything in Creation. If you believed in the rock in front of you, a percentage of that belief went to God. This usually ranged from 15 percent to 50 percent depending on the size of the object, with the rest of the belief going toward substantiating the object’s own existence. (Even this fail-safe plan had its problems. When the eighteenth-century philosopher Bishop Berkeley suggested that there were no “real” objects at all but only ideas, faith in the world of the senses wavered. The very God Berkeley had devoted his life to serving almost winked out of existence as people stopped believing in trees, rocks, and the rest of Creation. Fortunately for God, Berkeley’s theorem was refuted in 1753 when an idea fell on his head.)

Bishop Berkeley: Destroyer of Gods, Wearer of Hats.

To make matters worse, the number of gods was growing at an unbelievable rate. We all knew why this was. Olympus, where the new pantheon had their headquarters, had come to be known as “Mount” Olympus, so regularly was it shaken with the thunderous passions of the deities. The countryside surrounding it had become a quagmire of heavenly fluids, and vast, dirty underwear could be seen snagged in trees across half the earth. It was only the sudden onset of an ice age that prevented the entire planet from having to be dry-cleaned.

Heart of Darkness

I

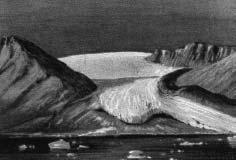

was fond

of glaciers, slow but amiable giants that bulldozed all the monocular and snake-haired skulls of the Age of Myth beneath them. I used to like watching them as they flowed into the sea to calve, the infant icebergs squealing and squawking with delight as they drifted away from the shore, while the mother glaciers broke out in bergschrunds and shed meltwater from every moulin in their fringe.

Ice, Ice Babies.

After the initial attack of hypothermia, the ensuing bouts of deadly frostbite, and the subsequent starvation of millions of people, my workload slackened. Humankind was forced to regress and regroup, and I was intrigued to watch the adaptations and innovations this new situation prompted. In my opinion, the most notable advance that the Ice Age fostered came with the rise of the Evil Villain.

Famous nowadays for tying damsels to train tracks, Evil Villains were not always so prevalent, or ingenious. Indeed, up until the Ice Age the early practitioners of Evil Villainy had been hampered in their calling by a lack of fast-moving locomotive devices with which to crush their victims in a suitably spectacular and horrifying manner. The rise of the glaciers, however, offered Evil Villains a temporary solution. Captive damsels were tied tightly to the snow line, and inch by inch, the giant tongues of ice slowly ran them over. Admittedly there were teething problems. The devilish process usually took from six months to two years, depending on the weather and the width of the damsel, and the Evil Villain was forced to keep his victim fed, watered, and warm throughout, if the full, shocking nature of his plan were to succeed. Many Evil Villains suffered hernias from having to sustain their diabolical cackling for months on end, and the lengthy intervening period between capture and slaughter meant rescues and escapes were common. I was assured, however, by the handful of people who were killed in such a manner that their ends had been “somewhat dastardly.”

Trains: Represented a Significant Technological Advance over Glaciers.

As all things must, even the glaciers had to die. I remember watching them retreating back to the poles, shrinking under the sun’s gaze, until in a lonely cwm, corrie, or cirque, they exhaled their final icy breaths and thawed into puddles, whereupon I popped out their dripping souls and sent them on their way. The earth returned to a more temperate clime, Evil Villains set to work creating the internal combustion engine, and the Age of Civilization finally began.