Dear Daughter (8 page)

Authors: Elizabeth Little

(But I made a few flashcards and wrote a short paper on nineteenth-century settlement patterns just in case you’re not.)

Then I was released, and all my ifs turned to whens. I sent Noah running around California putting together my new identity and ordering my new wardrobe, and while he was otherwise occupied, I planned my trip to Ardelle, mapping my route and booking a room at the only local inn that had a website. Here I caught a break: When I called to make my reservation, I spoke to the inn’s sweetly enthusiastic proprietress, a woman named Cora Kanty.

“You can’t come then!” she said when I asked about availability.

For a moment, I was nonplussed—

Other people wanted to visit this place?

—but I recovered quickly. “In that case, is there another hotel you can recommend?”

“Oh, no, that’s not what I meant! It’s just that if you can wait until November, you can join us for Gold Rush Days, our yearly festival! It’s great fun, especially if you’re a history buff like me.”

I thought through the possibilities. A festival would provide the perfect cover. There would be crowds to hide in, events to attend. If there was anyone named Tessa in Ardelle, I’d be sure to run into her. All I needed was a good reason to be nosy—which was where Rebecca Parker came in.

“November it is, then,” I said. “Because as it turns out, I’m absolutely

fascinated

by history.”

• • •

By the time Kayla’s shitty truck and I got to Ardelle, the sun was setting, and my immediate impression on arrival was that things would probably look a lot better once it was pitch dark.

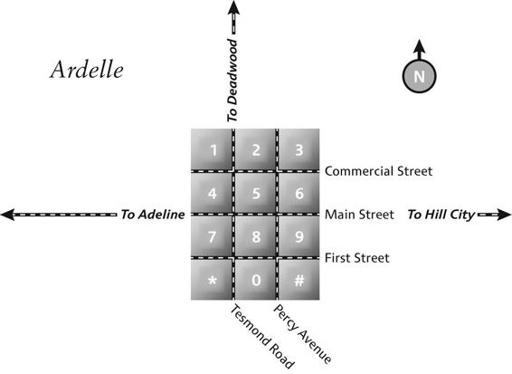

I hadn’t been able to find very much information about Ardelle, so I didn’t quite know what to expect. I knew the town was classified as a “census-designated place,” as kindly a euphemism as I can imagine for “one-horse Podunk shit hole.” I also knew its per capita income ($35,835), racial breakdown (White, 98.6 percent, American Indian and Alaska Native, 1.4 percent), median age (47.2), and primary industries (logging, mining, tourism). Even so, I had never imagined I’d find nothing more than a few dozen buildings hashed into twelve blocks by a grid of five streets.

I found it helpful to think of the town’s layout in terms of the buttons on a telephone, like so:

(For gas, press 6.)

(For groceries, press 2.)

(For city hall, press 5.)

(To speak to an operator—well, sorry, you’re shit out of luck, because anyone with that kind of vaguely marketable skill probably left town long ago.)

Most of the businesses I passed as I rattled down Main Street were already closed for the day—if, indeed, they had ever bothered to open at all. I parked the truck in the darkest corner of a lot off Percy, just past the inn. I checked my reflection in the rearview mirror. My eyes were wide and red-rimmed: I wasn’t used to wearing contacts, or that’s what I told myself.

I stepped out of the truck, walked to the street corner, and turned in a slow circle. According to my map, the town was built into a couloir—the eastern approach to the pass to Adeline, I guessed—with Main Street running the length of its nadir and transitioning from state highway to county road. If I squinted, I could see where Main Street then narrowed into a single lane of jagged asphalt and disappeared abruptly into the trees. The gully was sufficiently flat-bottomed to seat the town comfortably, but the mountain slopes rose so precipitously on three sides that it was impossible not to imagine the forest was about to fold in on you.

Just one house was set high in the hills. A Romanesque revival. Pretty. Incongruous.

When I looked down Main Street, I could see a dry cleaner, a hardware store, and a pool hall. Across the street was a single-screen movie theater playing a superhero movie even I knew had been released the previous spring. A few teenagers were milling about in front, disconsolately. I walked down to the inn, a dusky blue Queen Anne with a shingled roof and a wide front porch. Next to it was a church, a hulking and charmless pile of red brick that blocked out what was left of the sun, shadowing the inn in its own little wedge of premature twilight.

A gust of wind blew through the pass and slammed into me. My hand automatically came up to keep my hair out of my eyes, but my hair had been sweat-dried solid. An unexpected benefit of a stressful day.

I shivered. I’m no stranger to cold weather, of course, but things were different here. No sable muffs. No châteaux. No après-ski.

No mother.

I pulled my bulky blue jacket closed and tightened my gray fleece scarf. It smelled of plastic bag.

Something was wilting in the vicinity of my chest. I mean, seriously?

This

place? What connection could my mother possibly have to a town like this? She was as fastidious with her surroundings as she was with her attire, because she knew that even a D-flawless diamond looks like crap in a 10K setting. She had even considered

Beverly Hills

to be beneath her.

I turned and headed toward the inn. One thing made sense, at least: If my mother had known someone who lived here, no way would she have ever admitted it.

Ardelle, for those who haven’t had the pleasure of making its acquaintance, is nestled deep in the Black Hills, thirty or so miles from Mt. Rushmore, on the eastern slopes of Odakota Mountain. As we Ardellians know, our stunningly beautiful hometown was once little more than a gristly clutch of prospectors, founded in 1885 by J. Tesmond Percy’s Mining and Manufacturing Company and named, along with nearby sister-city Adeline, for Percy’s twin daughters. The population swelled in 1888 after Percy’s claim yielded three veins of gold, and by the 1890s Ardelle was a respectably sized town, with one church and three bars.

When the gold in Ardelle began to run low, the town sent a contingent west to the by-then-abandoned camp in Adeline to see if anything might be salvaged. Much to their surprise, a rich lode was found soon after! When the prospectors relocated, the shopkeepers went with them, and soon Ardelle became a town in name only.

Of course, the gold eventually ran out in Adeline, too.

But the rhythm of life in Adeline and Ardelle was set, as both towns were blessed with silver, tungsten, zinc, and tin. Over the next twenty years the local population moved from one side of the mountain to the other, depending on where the most lucrative mines of the moment were. These relocations happened so often that some families even built identical houses in each town to make things easier! Eventually, however, Ardelle’s comparative accessibility drew more and more of the local population, and today there are no full-time residents of Adeline. Even so, no one in Ardelle would call it abandoned. Adeline, they say, is simply waiting to be reborn.

—Cora Kanty,

Ardelle Women’s Historical Society

Newsletter

, vol. 1, iss. 1, January 10, 2011

CHAPTER EIGHT

When I stepped into the Prospect Inn I nearly tripped on my tongue. Now here was a room my mother would have approved of: It was neat, elegant, and dripping with money.

I wiped my shoes on the doormat before crossing what appeared to be the kind of antique Turkish rug that absolutely cannot stand up to foot traffic, which meant that it had been replaced no more than six months prior. To my left was the salon—well, you might call it the sitting room, but in my opinion any room that contains a recamier can only be called a salon—and to my right was the reception area. There, at a Hepplewhite desk, sat a slender girl with a paperback book, one delicate white hand floating over the corner of a page with the preternatural calm born of the knowledge that the world spun for her alone. She wasn’t waiting to turn the page. She was waiting with supreme confidence for the page to come to her.

I used to know what that felt like.

When she looked up, her hair caught the light of the lamp behind her, and I was momentarily incapacitated by the alteration it effected. Her strawberry-blond hair turned incandescent—like Greek fire, I thought. I scratched at the back of my own scalp, hoping it might urge the poetry out of my head. It isn’t easy to recalibrate after ten years of ugliness.

“Hello,” she was saying, “how can I help you?” Even her words were a power play, so painstakingly soft that I had to lean in to hear her. I was just like the page of her book: bending to her will.

I tamped down my first, second, and third through eighth responses, reminding myself that Rebecca Parker had probably never uttered a mean-spirited word in her whole boring life. “I have a reservation?” I said instead. “Last name Parker?”

She opened up a card file and picked through it. “You’re a day early.”

“I just couldn’t wait, I suppose.”

“Really.” She tilted her head to the side and then back, as if deciding how best to frame a photo. “You know, we have a girl in town who’s just magic with hair. I’m sure she could fit you in while you’re here.”

“That’s so sweet of you to offer,” I said, because it would’ve been a damn shame to come all that way only to get thrown in jail for strangling a bratty kid. And if I was going to get thrown in jail, it was going to be for a damn good reason.

“Well, that’s why I’m here. I’m Rue—I’ll be making sure you have everything you need while you’re with us.”

In that case, could you tell me if you happen to know someone named Tessa? Or you could just tell me if you happen to know if I’m a murderer—either way!

I shuffled to the side and made a show of scanning the room while I gathered my thoughts. To my left was a table laid with yellow cakes and a silver tea set. To my right was an oil painting that looked an awful lot like a Manet. In front of me was Rue’s book.

Her eyes were still trained on me.

Time to act normal.

“What are you reading?” I asked.

She lifted her eyebrows—which were golden and winged and looked like they’d never needed to be plucked in her life, damn her—but she answered me anyway. “

Jane Eyre

.”

“One of my favorites,” I lied.

She smiled. “Of course it is.”

I forced my hands to relax, when all I wanted to do was grab her by the neck and pitch her to the ground. You have to cut girls like Rue off at the knees if you don’t want them to eat your face off. I know that better than anyone.

• • •

The night my mother was killed, I went to a party at this girl Ainsley Butler’s house.

Ainsley’s parents were out of town that week—Cabo, probably; like their daughter, they had no imagination—and she’d promised an “epic” throw-down, which I’d decided to go to even though the only things that are consistently epic are bores, failures, and poems, insofar as those are separate entities. Later people would say I was there for the alibi. But honestly I just couldn’t bear the thought of another night at a club filled with actors and models and boys who weren’t embarrassed to be DJs.

Ainsley came from oil money—but not, like, Rockefeller oil. Upstart oil. Likes Louis Vuitton oil. Loves Showing Off oil. And so when Princess Ainsley decided she wanted to be the next Tori Spelling, her daddy up and moved the whole family into a faux Tudor monstrosity in Bel-Air. The desperate throngs of teenagers there that night, hurtling drunkenly against each other in the hope of stumbling into what would best-case scenario be a thoroughly mediocre orgasm, were a perfect complement to the décor.

When I arrived I crept around the edges of the party as inconspicuously as possible until I found my way to a room that might have been called a study had anyone in that house been capable of complex thought. In the back corner, beneath a reproduction Holbein, was what I was looking for: the sideboard. I poured myself a generous serving of something expensive and smooth and was nearly halfway through when I heard a snuffling behind me.

I turned to find a huddle of girls in front of the room’s staggeringly large sofa. They were young—twelve or thirteen—and tiny, hardly formed, that awkward stage between eft and newt. Soon enough they’d start buying big breasts and bigger bags of coke, and before long they wouldn’t dream of sitting in a circle unless it involved some kind of a jerk, but that night they were still little girls, and for a fleeting moment I wanted to gather them up in a bear hug and spirit them away someplace simple and straightforward, like—I don’t know, Glendale or Encino.

A chubby redhead mustered up her courage and stood. “Hi, Jane,” she said. She had the willfully cheerful voice of a preschool teacher. Her skirt wasn’t quite long enough to hide her dimpled knees.

I climbed onto a massively proportioned chair and pulled a pack of cigarettes out of my purse. As the girls awaited my response, they crowded together, expectantly, baby penguins angling for regurgitated fish.

“Mind if I smoke?” I asked, not that I cared. Back then I didn’t ask questions; I collected data.

They shook their heads emphatically. The redhead half raised her hand, requesting permission—actually requesting permission—to speak.