Dean and Me: A Love Story (24 page)

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

There was one important thing, Michael DeBakey told me: Coke and Percodan, he explained, were the same to me as coffee and cigarettes were to many smokers—inextricably bound, one triggering the need for the other. I must never let Coca-Cola pass my lips again. My dentist was delighted.

The following year, I was able to go back to moviemaking for the first time in almost a decade. The picture was called

Hardly Working

. We shot it in Florida, and the whole experience was a very mixed bag. I directed, cowrote, and starred, and I have to admit that the awful strain of the past ten years showed in every part of my work. The movie didn’t really hang together, and not so surprisingly, I looked terrible in it.

Still,

Hardly Working

had some good moments onscreen and off. When the film was released in Europe, it turned out that audiences had missed me: They bought $25 million worth of tickets. And once we were finally able to get a distributor in the States (it wasn’t easy, because of how long it had been since my last picture), the critics, who had a field day putting the movie down, were amazed to see it sell.

But the best thing that came out of

Hardly Working

was a little scene I did with a fresh-faced young dancer from North Carolina named Sandra Pitnick, nicknamed SanDee, or Sam. Out of that scene came a friendship, from that friendship came a relationship, and from that relationship came a new life. After Patti and I made the agonizing decision to bring our long and difficult marriage to an end, Sam and I became husband and wife in February 1983.

It was just a couple of weeks later that Sam and I went out to dinner in Beverly Hills with my manager Joey Stabile and his wife Claudia, who ran my office. The restaurant was La Famiglia, on Rodeo a couple of blocks north of Wilshire. We’d picked it out because we all felt like some Italian food. Who knew that it was Dean’s favorite restaurant?

I spotted him the moment we’d been seated: He was alone in a red-leather booth by the front door. After a moment, I caught his eye and waved. He waved back. I got up and walked over to his table.

My first reaction as I approached was a double take at how much Dean had aged. I know I was no Prince Charming, but my partner had always looked so magnificently handsome and youthful. He was about to turn sixty-six. There are young sixty-sixes and old sixty-sixes, and Dean was definitely the latter. Whether it was the effects of the sun for all those years, or the accumulated sadnesses of his life, or just the genetic luck of the draw, I don’t know. But it saddened me deeply.

“You workin’?” I said, putting on a brave smile.

He laughed at that, and it made him look younger. “You wanna have a drink?” he asked.

“No, I don’t drink,” I told him. “I used to work with a guy that drank all the time and breathed on me—I’ve had all the booze I can take for one lifetime.”

He laughed again. It was all very playful. But at the same time, I felt that I was imposing on him. With age, his reserve had grown. (Mack Gray, the one man who was at all close to Dean in later years, had died in 1981.) Dean could have had almost anybody in the world in that booth with him—a gorgeous girl, Frank, anyone—but he truly wanted to be alone. I touched his arm, gave him a wink, and went back to my table.

Ten minutes later, a waiter brought over a champagne bucket, covered with a cloth napkin. “Compliments of Mr. Martin,” the waiter said.

I finally went to hell.

I removed the napkin and saw six bottles of Diet Coke sitting on ice.

I laughed out loud, not just at the joke—it was classic Dean!—but with a kind of relief. He hadn’t closed me out. I patted Sam on the hand. “Come on,” I told her. “I want you to meet him.”

She hesitated. Sam is deeply sympathetic to others’ feelings, and that’s just one of the reasons I’m so nuts about her. She didn’t want to impose—on Dean’s privacy, on my relationship with him.

But I felt strongly about this. “Come,” I said. “This is important to me.”

We walked over to his table. Just for a second, I went into the Idiot voice: “Thank you for the lovely champagne.”

He laughed, and I had my opening. “Paul, I want you to meet my wife, Sam.”

He looked up at her with a grin. “I always knew you’d marry a guy.”

We all laughed. We stood there chatting for a couple of minutes, and it was nice, but once more I picked up on his wish to be by himself. We went back to our table.

I couldn’t take my eyes off Dean after that. Staring across the restaurant, trying to get my mind around how much he had changed. A million images of the old days, when we were both kids, flashed through my brain.... Christ! Don’t get old, I thought.

What’s the alternative?

As we ate, I watched him eat. It’s a very strange thing to watch someone you know well eating alone. I tried my hardest not to be sad, but the feelings washed over me. One thing I did notice: Dean had an Old-Fashioned glass in front of him, and it sat there, full, for his whole meal. He never touched it.

Then, one day not long after that, I found—it both surprised me and didn’t surprise me at all—that I missed him. So I called him up. As simple as that.

“Hey, Paul—how ya doin’?” I said, bright and chipper.

“Hey, pally. How are you?”

“What, you forgot my fuckin’ name already?”

We had a few laughs, chatted for a few minutes. Nothing important—it was more about the music than the words. It was easy, and lovely, and it didn’t last one second more than it had to.

So every couple of weeks afterward, I called him again. It went on that way for four years.

Dean had seven children, and he loved them all dearly, but Dean Paul Martin Jr., his second son and his first child with Jeannie, was the apple of his eye. Dino, as they called him, truly was a golden boy. Blond like his mother, and sharing both his parents’ good looks, he was a talented musician (like my son Gary, he’d had a successful rock recording career in the mid-sixties) and a brilliant athlete—for a time he played tennis on the professional circuit. He also did some acting in the movies and on television; still, it wasn’t any picnic trying to succeed in that profession as Dean Martin’s son. In his mid-thirties, Dino was working hard to make his own way in the world.

And Dean admired the hell out of that. He could tolerate very few people, and he admired almost nobody, but God, he looked up to that boy. To top it off, Dino was a captain in the Air National Guard: He flew jet fighters every weekend. To Dean, who wasn’t crazy about air travel, that seemed amazingly brave.

On March 20, 1987, Dean Jr. was on maneuvers over the San Bernardino Mountains when his F4-C Phantom went off the radar screen. The wreckage of the plane was found five days later. Dino and his weapons officer had been flying into a blizzard in white-out conditions. When they lost radio contact with air-traffic control, they crashed into Mount Gorgonio.

I was playing at the Bally with Sammy when I heard about Dino’s death. I immediately flew to L.A. for the funeral. I walked into the back of the church at the beginning of the service, and I stayed there. Dean didn’t know I was present, and I didn’t want him to.

Afterward, I said to Sam, “Honey, it’s just a matter of time. Dean’s gone. That boy was the most important thing he had in his life.”

Early that evening, Greg Garrison, Dean’s television producer and a friend of both of ours, phoned to say that he’d seen me at the funeral and told Dean. Greg said that Dean was so touched that I’d been there. What he didn’t say, but what I understood, was how moved Dean had been that I’d come and gone in anonymity. Going unnoticed has never been my strong suit. But I felt it was a gesture I owed to both my partner and Dino.

Late that night, after my second show at Bally’s—it was about three A.M.—the phone in my dressing room rang. The voice on the line was instantly recognizable.

“Hey, Jer.”

In our phone relationship of the last few years, I’d always been the one to place the call. That was just the way it went with Dean, and I never minded, but this night was very different.

We talked for an hour. He cried, I cried. I said, “Life’s too short, my friend. This is one of those things that God hands us, and we have to somehow go on with our lives. That’s what Dino would have wanted.” I was trying to get him to see that he had to find a way to go forward. But all he kept saying was, “Jer, I can’t tell you.”

I wanted to get together with him, but I sensed Dean preferred talking on the phone, so I respected that. I called him whenever I could, as often as I could without feeling I was intruding. The conversations always began the same way.

“Hey, Paul, how you doin’?”

“How you doin’, pally?”

“You

still

don’t remember my fucking name?”

Now and then, he even laughed.

In the spring of 1989, I saw an announcement that Dean was going to play Bally’s in Vegas. I was impressed:

He’s found a way to go on

, I thought.

I stayed away, though, not even sneaking in to see him perform. I wanted him to have his own space.

Then one day I looked at my calendar and saw that it was June 6. The next day, unbelievably enough, would be my partner’s seventy-second birthday.

I phoned Claudia Stabile and told her to buy the biggest and best cake she could possibly find, have it delivered to Bally’s, and get somebody to guard it until I got there. We planned the whole thing with military precision. I found out what time Dean went on stage and arrived at the club a few minutes later. The management knew me well, of course; everyone was in on the plan, including Dean’s conductor and pianist, Ken Lane.

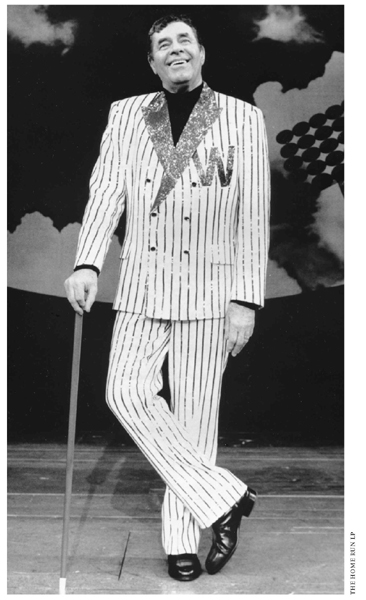

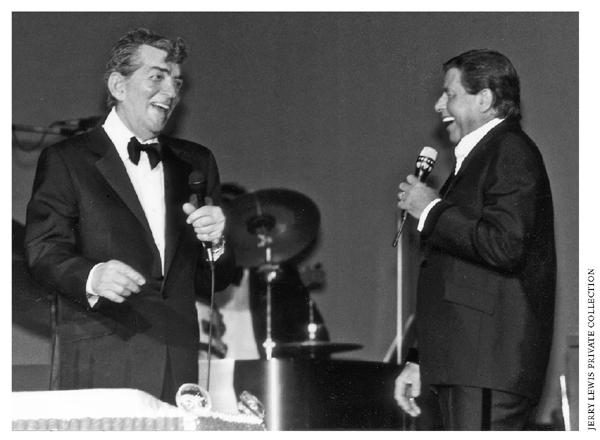

Birthday cake at Bally, 1989.

I went backstage while Dean was on and watched him from the wings for around twenty minutes. He was wonderful. Ken had told me there was a certain point in the show when Dean bowed off and exited— stage right, as always. After that, Ken would play the introduction to the next number and Dean would come back out. This all went exactly as planned, except when Dean returned to the stage, Ken stopped the music and I yelled from the wings, “How the hell long are you gonna stay on?”

Dean looked startled, turning toward the familiar voice, Ken cued the band into “Happy Birthday,” and I wheeled that giant cake out onto the stage. The place went apeshit.

“You surprised me,” Dean said. He held his arms out. His eyes were full of tears. I blinked hard, not wanting to start bawling in front of 1,500 people.

As we hugged, he said, loud enough for the audience to hear, “I love you and I mean it.”

And this is what I said, also loud enough for everyone to hear: “Here’s to seventy-two years of joy you’ve given the world. Why we broke up, I’ll never know.”

’Nuff said.

AFTERWORD: GOOD-BYE, HELLO

I HEARD THE NEWS FLASH WHILE I WAS IN DENVER, ON TOUR with Damn Yankees. The devastating bulletin came at 8:30 in the morning on Christmas Day. I was stunned, terrified, not believing any of it, and still knowing it was real. It had happened. I had lost my partner.

When I finally pulled myself together, I hired a private jet to fly to Los Angeles as soon as possible, to be with his family—and with

him

.

My four-year-old miracle daughter came home from school around 3:30—and when I saw her face, the pain of the reality of that day shook me again. I hugged my Princess ... thinking of the life we’d lost, but holding on to this new life. Danielle helped me pull it all together.

Sam and Dani went with me to the airport. I didn’t want them to have to go to a funeral. In fact, if it hadn’t been Dean’s, I wouldn’t have gone at all. I believe funerals are fundamentally uncivilized. If you have something good to say about a person, for Christ’s sake, say it to their face while they’re still alive. It doesn’t mean squat to them after they’re gone!

I arrived in Los Angeles in time for the memorial service—thank God, I missed the burial itself. I was asked to speak, and I prayed I would have the strength to say what I had to say without breaking down: I knew Dean would have called me a wuss if I had.

I told the people, “You are so lucky that you knew my partner and my friend. I will not fall into that drone of pain about death, but I will ask you all to just yell ‘Yeah!’ that he lived... that he was with us for all that time. ‘Yeah!’ ‘Yeah!’ And that, my friends, is my celebration of his life. Long may he drink!”

I stepped down from the podium and walked to my seat. I stopped along the way to kiss Jeanne.... He loved her so much. I sat down next to Lew and Edie Wasserman. The names who were there would have made the

Hollywood Reporter

envious.

Outside, I met Frank. He grabbed my hand and said, “Well, we lost the big gun, my friend!”

I said, “We didn’t lose him, God just placed him elsewhere.”

Frank said, “Yeah, I know. How you holding up, Jew?” That’s all Frank ever called me, for fifty-one years, and I loved it. We held hands like two kids, not knowing what to say next. Thank God, I had to get back to the plane. I boarded the jet—and the tears came.

I lost my partner and my best friend. The man who made me the man I am today. I think of him with undying respect. I miss him every day I’m still here. I’ve considered the idea of our getting together again someday, but I believe when we die we are just put away and life goes on. My prayer to be with him again isn’t realistic, but I’ll live the rest of my life with the memory of a great and wonderful man, my partner, Dean Martin... G.R.H.S.

So many memories flash and flicker around my brain—and the strangest ones come up at the strangest times. Why am I thinking, now, about those first crazy shows we did, way back before we were even a team, at the Havana-Madrid in the spring of ’46?

I’ve told you already about all the insane things I did to get Dean’s attention while he was performing, just to try and make him laugh. And how scared I was, at first, that he wouldn’t like what I did—and then, when I came out of the kitchen with that goddamn hunk of raw meat on a fork, he smiled, and it was like the sun coming out on the rest of my life.

Something else just popped into my mind.

The third or fourth night into my relentless menu of stunts, I realized that no matter what I did, short of lighting a stick of dynamite on stage, Dean would do takes, throw lines, and just go right on singing. (Most songs run two and a half to three minutes; with my help, his could run eleven or twelve.) That was the wonder of it all, the fun and joy of it all—but being nineteen years old, I couldn’t help but want to try to top myself. Then I had an inspiration.

As I said before, the staff at the Havana-Madrid was even more enthusiastic about our go-for-broke craziness than the few patrons who were still around in those early-morning hours. And so when I approached the guy who ran the lighting board with my idea, I knew right away that I had a willing accomplice.

Dean had gotten a little ways into “Pennies from Heaven”—up to the line that goes, “Save them for a package of sunshine and flowers”— when I hit the main switch and the whole place went black.

The musicians fumbled along for a moment, then stopped dead.

And Dean—of course!—never hesitated for a second. You think he had any doubts about what had just occurred, and who was behind it? No, going on with his number (even a capella) was a matter of pride for him at that point—and in one of those lightninglike inspirations I would soon learn he was capable of, he instantly figured out a way he could be seen as well as heard. He took out his gold-plated Zippo cigarette lighter, flicked the flint, held the flame under that unbelievably handsome face, and finished his song in the mellow flicker of its flame just as though nothing at all had happened.

No, scratch that. He finished up that goddamn number even more stylishly than if the spotlight had been right on his face.