Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (29 page)

Read Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All Online

Authors: Paul A. Offit M.D.

BOOK: Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All

8.26Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

On January 20, 1961, during his inaugural address, President John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country.” Twenty years later, Ronald Reagan, during a debate with President Jimmy Carter, asked, “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?” Both men understood the prevailing mood. Kennedy had appealed to a sense of community, sending thousands of young people into programs like the Peace Corps and Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA); he asked Americans to see themselves as part of something greater, to take responsibility for something greater. Reagan appealed to the “Me Generation”; now it was time for me to get mine.

A parallel can be drawn with vaccines. On February 2, 2009, a show titled “The Polio Crusade” aired on public television’s

American Experience

. The program described a polio outbreak in the summer of 1950 that devastated the town of Wytheville, Virginia. And it told the story of America’s efforts to make the first polio vaccine. It’s a remarkable program. Throughout the documentary are heard the voices of Americans sixty years ago, and they reveal a heart-warming sense of community. People saw polio as a shared tragedy, giving millions of dollars to the March of Dimes to make a vaccine. And they gave more than their money; thousands of community organizers volunteered to conduct the largest field trial of a vaccine ever performed—one that included about two million children. When it was over—when a polio vaccine emerged that eliminated the disease from the Western Hemisphere—Americans were proud. They felt that they, more than anyone else, had developed the vaccine. Individuals saw themselves as part of a group—a public that cared about public health. It was this sentiment that John F. Kennedy so deftly touched during his inaugural address.

American Experience

. The program described a polio outbreak in the summer of 1950 that devastated the town of Wytheville, Virginia. And it told the story of America’s efforts to make the first polio vaccine. It’s a remarkable program. Throughout the documentary are heard the voices of Americans sixty years ago, and they reveal a heart-warming sense of community. People saw polio as a shared tragedy, giving millions of dollars to the March of Dimes to make a vaccine. And they gave more than their money; thousands of community organizers volunteered to conduct the largest field trial of a vaccine ever performed—one that included about two million children. When it was over—when a polio vaccine emerged that eliminated the disease from the Western Hemisphere—Americans were proud. They felt that they, more than anyone else, had developed the vaccine. Individuals saw themselves as part of a group—a public that cared about public health. It was this sentiment that John F. Kennedy so deftly touched during his inaugural address.

Sears, like Reagan before him, is appealing to a generation that doesn’t consider a larger cooperative—an immunological commons. Toward the end of his book, under the heading “Is It Your Social Responsibility to Vaccinate Your Kids?” he writes, “This is one of the most controversial aspects of the vaccine debate. Obviously, the more kids who are vaccinated, the better our country is protected and the less likely it is that any child will die from a disease. Some parents, however, aren’t willing to risk the very rare side effects of vaccines, so they choose to skip the shots. Their children benefit from herd immunity—the protection of all the vaccinated kids around them—without risking the vaccines themselves.” Sears then asks the critical question. “Is this selfish? Perhaps. But as parents you have to decide. Are you supposed to make decisions that are good for the country as a whole? Or do you base your decisions on what’s best for your own child as an individual? Can we fault parents for putting their own child’s health ahead of other kids around him?” In another section of the book, Sears doesn’t hide the deceit. Regarding parents who are afraid of the MMR vaccine, he writes, “I also warn them not to share their fears with their neighbors, because if too many people avoid the MMR, we’ll likely see the diseases increase significantly.” In other words, hide in the herd, but don’t tell the herd you’re hiding. Otherwise, outbreaks will ensue. Sears’s advice was prescient. Within a year of the publication of his book, the United States suffered a measles epidemic that was larger than anything experienced in more than a decade. (It was an outbreak fueled by the unfounded fear that MMR vaccine caused autism—a fear that Sears fails to allay in his book.)

Now that herd immunity has broken down, Sears’s position that one should think only of oneself no longer works. Unfortunately, his book contains many examples of this philosophy:

• “In truth, tetanus is not an infant disease,” he writes. “Also, diphtheria is virtually non-existent in the United States. So you could create a logical argument that a baby could skip the tetanus and diphtheria shots for a few years and be just fine.” These statements are inaccurate. First: tetanus

is

a disease of infants. A cursory look at any textbook of infectious diseases provides grim pictures of newborns suffering severe muscle spasms and breathing difficulties from tetanus; that’s why it’s called the “disease of the seventh day.” Second: the casual advice that one can simply wait to get a diphtheria vaccine ignores history. Between 1990 and 1993, when public health programs were disrupted in the Russian Federation (states newly independent from the Soviet Union), a hundred and fifty thousand people suffered diphtheria and five thousand died, mostly children. In the absence of vaccination, such an outbreak could happen in the United States just as easily.

• “[Polio] doesn’t occur in our country,” writes Sears, “so the risk is zero for all age groups.” Although polio has been eliminated from the United States, it hasn’t been eliminated from the world. Four countries—India, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan—have never interrupted polio transmission; and children in twenty-three other countries still suffer the disease. Because international travel is common, and because most people who are contagious aren’t sick, it is likely that poliovirus walks into the United States every year. Children whose parents follow Sears’s advice will be particularly vulnerable when an outbreak occurs or when they travel overseas.

• “Hib is a bad bug,” writes Sears. “Fortunately, it’s also a rare bug, so rare that I haven’t seen a single case in ten years. Since the disease is so rare, Hib isn’t the most critical vaccine.” As Sears knows, Hib is rare because of the Hib vaccine. And if we stop using the vaccine, Hib will be back. Which is exactly what has happened. Sears’s book was published in October 2007. The following year, outbreaks of Hib meningitis occurred in Minnesota and Pennsylvania. All these outbreaks centered on children whose parents had chosen not to vaccinate them; four died from their infections.

Robert Sears peers out from the back cover of his book with an open, caring expression, exuding a kind of California calm. No doubt he wants to do the right thing; no doubt he is trying to find some middle ground between parental anxiety about getting vaccines and physician anxiety about not giving them; no doubt he believes he is on the side of his fellow physicians. Describing his “alternative schedule,” Sears writes, “I have put together a vaccine schedule that gets children fully vaccinated, but does so in a way that minimizes the theoretical risks of vaccines. It’s the best of both worlds of disease prevention and safe vaccination.” But Sears’s schedule is ill-founded. And rather than calming parents with science that exonerates vaccines, he caters to their fears by offering a schedule that has no chance of making vaccines safer and will only increase the time during which children are susceptible to infections that can kill them. It’s the worst of both worlds.

Although Sears is probably well meaning, one has to question the hubris of a man who decides to create his own vaccine schedule—someone who claims his schedule is better and safer than that recommended by the CDC and AAP. It’s all the more amazing when one considers that Robert Sears has never published a paper on vaccine science; never reviewed a vaccine license application; never participated in the creation, testing, or monitoring of a vaccine; and never developed an expertise in any field that intersects with vaccines—specifically, virology, immunology, epidemiology, toxicology, microbiology, molecular biology, or statistics. Yet he believes he can sit down at his desk and come up with a better schedule. And parents trust him. Oddly, they trust him

because

he doesn’t have an expertise in vaccine science—an expertise that would likely have inspired the CDC, AAP, FDA, professional medical organizations, or vaccine makers to seek his advice.

because

he doesn’t have an expertise in vaccine science—an expertise that would likely have inspired the CDC, AAP, FDA, professional medical organizations, or vaccine makers to seek his advice.

One final irony. For a new vaccine to be added to the schedule, the FDA requires concomitant-use studies. Pharmaceutical companies must show that a new vaccine doesn’t interfere with the immunity or safety of existing vaccines and that existing vaccines don’t interfere with the new vaccine. Only then can a vaccine become part of the schedule. Dr. Bob’s schedule, on the other hand, is completely untested—never reviewed by the FDA, CDC, or AAP to make sure it’s as safe and effective as the existing schedule. It is remarkable how little Sears thinks of the enormous amount of testing that goes into creating the current schedule.

Sears isn’t alone.

On January 12, 2010, Dr. Mehmet Oz, host of the popular

The Dr. Oz Show

, told interviewer Joy Behar what he thought about the influenza vaccine.

The Dr. Oz Show

, told interviewer Joy Behar what he thought about the influenza vaccine.

BEHAR:

There’s a rumor that your kids did not get flu shots or swine flu shots. Is that right?OZ:

That’s true. They did not.BEHAR:

Do you believe in them for the kids or what?OZ:

No. I would have vaccinated my kids but you know I—I’m in a happy marriage and my wife makes most of the important decisions as most couples have in their lives.

Given their relative training, one would have imagined that Oz, not his wife, would have made the decision. Mehmet Oz graduated from Harvard University in 1982 and obtained a joint MD and MBA degree from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and the Wharton School in 1986. Since then, he’s climbed the ranks to become a professor of cardiac surgery at Columbia University. His wife, Lisa, has no background in science or medicine. Rather, Lisa Oz is guided by the beliefs of Mikao Usui, who, after three weeks of fasting and meditation on Mount Kurama in Japan, claimed he had been given the power to heal through his palms—called reiki. Lisa Oz isn’t just a follower of Usui, she’s a reiki master.

The four Oz children weren’t among the hundreds of thousands hospitalized or the hundreds killed by swine flu in 2009. But they could have been. And the influenza vaccine would have prevented it. No scientific evidence supports palm healing as a method to treat or prevent influenza.

Oz’s disdain for vaccines didn’t end on

The Joy Behar Show

. In December 2009, Oz and co-author Michael Roizen published

YOU: Having a Baby

, a book that promotes Dr. Bob’s Alternative Vaccine Schedule. Oz and Roizen wrote, “One of the most highly charged conflicts revolves around an issue that comes up just moments after your baby is born: to vaccinate or not to vaccinate? That, indeed, is one heck of a question.” Like Sears, Oz and Roizen misinformed their readers on several counts:

The Joy Behar Show

. In December 2009, Oz and co-author Michael Roizen published

YOU: Having a Baby

, a book that promotes Dr. Bob’s Alternative Vaccine Schedule. Oz and Roizen wrote, “One of the most highly charged conflicts revolves around an issue that comes up just moments after your baby is born: to vaccinate or not to vaccinate? That, indeed, is one heck of a question.” Like Sears, Oz and Roizen misinformed their readers on several counts:

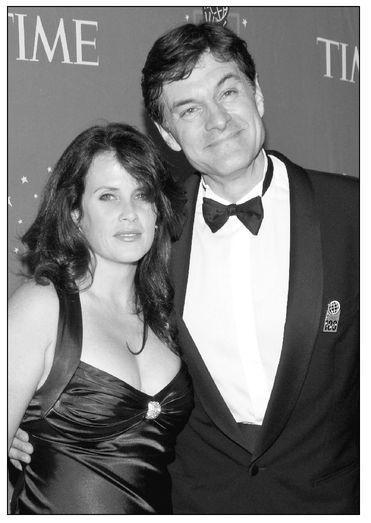

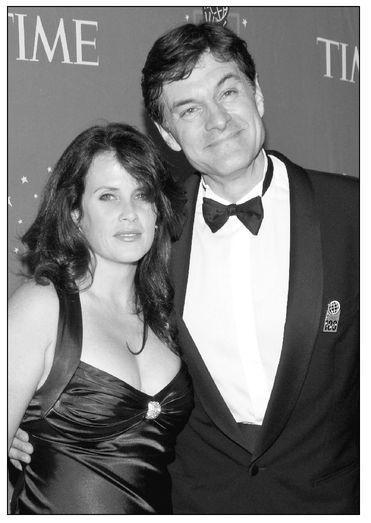

Mehmet Oz, host of

The Dr. Oz Show

, often dispenses anti-vaccine advice. Shown here with wife Lisa at

Time

magazine’s 100 Most Influential People Gala, May 8, 2008. (Courtesy of Scott McDermott/Corbis.)

The Dr. Oz Show

, often dispenses anti-vaccine advice. Shown here with wife Lisa at

Time

magazine’s 100 Most Influential People Gala, May 8, 2008. (Courtesy of Scott McDermott/Corbis.)

• Regarding the polio vaccine, they wrote, “There’s no doubt that polio vaccine ... causes polio in 1 in 1 million to 2 million,” failing to mention that the only polio vaccine available today in the United States is inactivated and, therefore, incapable of causing polio.

• Regarding the influenza vaccine, they wrote, “Pregnant women should avoid getting the influenza vaccine in their first trimester.” Instead of the vaccine, they suggest that “you can boost your immune system during the winter by taking 2,000 IU [International Units] of vitamin D daily.” Pregnant women are much more likely to be hospitalized and killed by influenza than nonpregnant women of the same age. That’s why they’re asked to receive the influenza vaccine if they’re pregnant during influenza season. The vaccine, not vitamin D, induces specific immunity to the virus.

• Regarding the rotavirus vaccine, they wrote, “A prior version of this vaccine was withdrawn from the market in 1999 because it was linked to a severe condition known as intussusception, a blockage or twisting of the intestine. A new vaccine, released in 2006, has been associated with even more cases of intussusception ... than the first version, prompting an FDA notification in 2007. We recommend that you opt out of this one until more data are available.” Oz and Roizen should have read the FDA notification a little more carefully. If they had, they would have seen that the FDA stated that all cases of intussusception following rotavirus vaccine may have occurred by chance alone. Further, one year before

YOU: Having a Baby

was published, the CDC found the risk of intussusception was the same in children who did or didn’t receive the rotavirus vaccine; parents no longer have to wait for data.

Robert Sears and Mehmet Oz have followed in the footsteps of anti-vaccine activists before them, claiming to inform parents about vaccines while in fact misinforming them. Their popularity has only widened the gap between some parents and their pediatricians.

Other books

Balas de plata by David Wellington

Ivy Takes Care by Rosemary Wells

Acoustic Shadows by Patrick Kendrick

Give Up the Body by Louis Trimble

Mardi Gras by Lacey Alexander

United We Spy (Gallagher Girls) by Carter, Ally

Sektion 20 by Paul Dowswell

Raymie Nightingale by Kate DiCamillo

LOVING ELLIE by Brookes, Lindsey

The Oracle Glass by Judith Merkle Riley