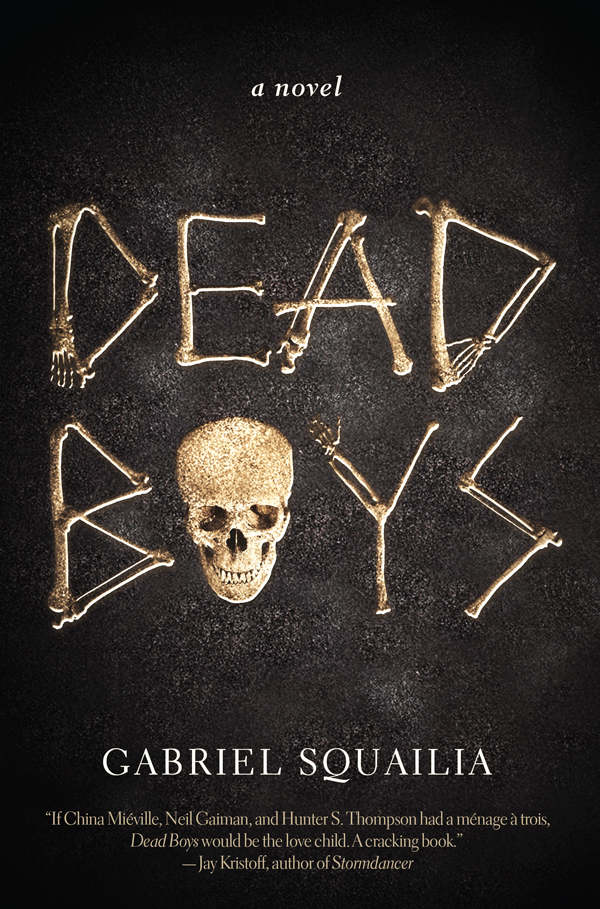

Dead Boys

Authors: Gabriel Squailia

Copyright © 2015 by Gabriel Squailia

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Talos Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Talos Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Talos Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

[email protected]

.

Talos Press is an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at

www.talospress.com

.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Brian Peterson

ISBN: 978-1-940456-24-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-940456-29-4

Printed in the United States of America

for Najwa

When the mind renews itself without forming new patterns, habits, without again falling into the groove of imitation, then it remains fresh, young, innocent, and is therefore capable of infinite understanding.

For such a mind there is no death because there is no longer a process of accumulation. It is the process of accumulation that creates habit, imitation, and for the mind that accumulates there is deterioration, death. But a mind that is not accumulating, not gathering, that is dying each day, each minute—for such a mind there is no death. It is in a state of infinite space.

—J. Krishnamurti

I

CHAPTER ONE

On Southheap

H

olding out both of his leather-palmed hands for balance, the gentleman corpse known as Jacob Campbell thrust a boot into Southheap. Infinitesimal bits of burnt plastic, chipped wood, and styrofoam plinked down the slope. When no landslide followed, he staggered forward with all the grace of a marionette operated by a novice.

“Chin up, now,” he said to himself in a tight-throated voice, “just put one foot in front of the other, and you’re all but guaranteed not to spend eternity in pieces.”

For years, Southheap had hulked in the distance through the window of his Dead City flat, so huge, familiar, and featureless that he gave it no more thought than the sepia skies. Even when he’d planned this journey, it hadn’t occurred to him to wonder where all this garbage had come from, much less why a population obsessed with scavenging had tossed it all aside. Now that he’d spent the better part of a week watching it slide and skitter beneath his weight, he knew more than he cared to. With every step, Southheap spilled its grotty secrets between his feet, threatening to break or bury him, or both, if he dwelled too long on what he’d seen.

The surface of this colorless mound had been dumped here one bucket, one barrow-load at a time, that much was obvious. But its core, he’d realized during the past few days, had been deposited by the whims of the river over the course of centuries. Whenever she flooded, Lethe toyed with the structure of Southheap as surely as she reordered the city below, and no dead man knew how or why.

Jacob trod on a trove of moldering newspapers that crumbled into sand and ink at the touch of his sole. He tottered backward, finding his footing a moment before the scree shifted. Trembling, he watched a shelf of garbage tumble down toward the river’s edge, exposing a curved talon of iron rebar that would have impaled him had he trusted that step for a moment more.

“I should’ve sent a damn debtor,” he whispered. So far as he knew, no one who could afford this trip made it themselves, for reasons that became clearer every hour. He’d made up his mind, however, that his business here was too important to entrust to a hired hand. Despite the danger, he meant to begin his quest as he hoped to end it: with his own hard-won strength.

As Jacob picked his way toward a remnant of the spiraling path that debtors of old had built to dump their barrows of trash, he heard a clanging from the city below. They were ringing the hour in the crumbling minaret near his flat in the Preservative District. It was four in the morning, though it looked, as ever, like a hazy afternoon. He tallied five days and fourteen hours since he’d left the comfort of home, a length of time that might well have sent him spiraling into despondency had its echoes not been accompanied by his first glimpse of the fortuneteller’s dwelling.

Just beyond the edge of the path, an upended water tower was half-buried in a mound of debris, and beyond its rusted curve lay a view of the River Lethe unparalleled in the city proper. Jacob, despite his unmoving lungs, gasped.

Its purplish waters were wide and slow-moving. The motionless corpses that floated on its surface were surrounded by glittering shoals of refuse and roiling rainbows of oil. There, past the bobbing shape of a claw-footed bathtub, was the stretch of river-bend where he’d thrashed out of the mud and onto his newly lifeless feet nearly a decade ago. With this unexpected glimpse of his point of deathly origin, it all came rushing back: how, after days of toil, he’d propped his numb body up on one palm, then another, only to lose his purchase in the slippery mud and splash face-first into those amniotic waters, where the whole humiliating process began anew.

Dazed by the memory of his quickening, and by that of his death that lay in hiding behind it, Jacob took a single thoughtless step.

One was enough. His arms windmilled, too wildly, too late, and he fell backward, landing with a crash on the lumpen cushion of his overstuffed knapsack. Scrabbling at the surface of Southheap, he screamed for help to no one, then bit off the sound as the ground beneath him gave. The underworld blurred and tumbled, all beige skies and thundering rubbish, and all he could think was how

close

he’d come before the end.

For there could be no question that his quest was over. He could hear the rush becoming a roar behind him as he somersaulted onto his belly. Riding a cresting wave of detritus, he saw a thin wall of scrap metal approaching and jammed his hands down and to the left. With inches to spare, he tumbled away from that serrated edge and thumped into the gray-green curve of a rotting featherbed.

Keening in gratitude, he lifted his head to witness the cascade thundering past. His spine would have snapped in two, and his crumpled halves would have been buried for the rest of time, or at least until the next flood. He fell back onto the mattress and shuddered: if anything could be worse than spending an endless existence buried in a landfill, it would be lying in the mud at the bottom of Lethe, watching his body deliquesce.

The bells seemed to speed up as he lay inert, thanking the starless sky. An hour passed, then twelve, then twenty-four. Finally he sat up, checking his arms, then his legs, then the rest.

Somehow he hadn’t broken so much as a toe. It was a miracle. No: a

blessing

.

He tugged the plastic vial from a pocket in his knapsack and pressed it to his shrunken lips. He’d never been so sure of the rightness of his path. Now if only he could stay on it—and stay vertical!

Hampered by the grip of his rotting musculature on his bones, he resumed his ascent, twice as carefully as before, but without any undue worry. In life, such a setback might have distressed him, even sent him into a panic, but in the underworld, the time he’d lost was utterly insignificant. Like any other corpse, Jacob had no need for rest or nourishment, and any occupied hour was a relief so long as his body remained whole, mobile, and suitably preserved.

He spent another seven such hours regaining the ground he’d lost. Giving his full attention to his footsteps, he was surprised at how well-tended the interrupted path became as it led to the seer’s door. Someone had packed it down, forcibly and recently. Stepping lightly now, he rubbed his reupholstered palms together, the high-pitched scrunch of their leather soothing his mind.

“Greetings!” he cried, jerking one hand over his head, but as soon as he’d had a good look into the murk of her chamber, he choked on his prepared speech. From the roof to the rust-bitten curve of the floor, the room was packed with filth-encrusted children’s toys. Quilts and blankets spewed moldy down onto jacks-in-the-box with broken springs. Board games missing their pieces served as tables for eyeless dolls. In the center of the candy-colored sprawl sat the seer known as Ma Kicks, her body so thoroughly ravaged by time that Jacob felt a professional ache at the sight. From forehead to foot, her skin was full of holes, flashing elbows, cheekbones, and knuckles alike. Her face was a soiled handkerchief askew on her skull, incapable of expression.

“My name is Jacob Campbell,” he said, steadying himself enough to bow. “I come with a gift—and an uncommon question.”

Ma Kicks still hadn’t moved, but at the sound of his voice, something within her did. Startled, he staggered backward, fixing his attention on her belly.

She must have been near her ninth month of pregnancy when she’d died. Since then, her womb had given way, and from its dark cavity two tiny, skeletal feet emerged, dangling over the edge, kicking into the open air.

“What’s that?” she whispered, bowing her head. “Oh. All right. If we got to, we got to.” Looking up, she seemed to notice Jacob for the first time. “Strange. Strange agent you are. What’s your name, now?”

“Jacob,” he said, uneasy at repeating such simple information. “Jacob Campbell. May I be so bold as to—”

“Why’d you come?” Her hands drifted with maddening languidness toward her baby’s feet.

“As I said, I came to ask—”

“I don’t mean what

for

,” she said, her voice as slow as molasses. One decimated hand found the child’s toes and slowly wiggled over them. “

Coochee-coo

,” she murmured, then looked up again. “I mean why

you

. Everybody sends somebody. Nobody comes up here himself. That’s the whole point.”

“The point of

what

?” said Jacob. Had Ma Kicks been away from the company of corpses so long that she’d gone mad? Or had she always been this way?