Dating is Murder (15 page)

The man walked out of RockiSushi.

We all looked at one another, the chef, the staff, the

B.C.

people, the five customers. Two or three cell phones came out. “Do we call 911?” a woman at a table asked.

“Did anyone die?” Fredreeq said.

Paul went over to Bing, who was nursing his hand. Bing told Paul to get lost.

Joey, meanwhile, had crossed the room and picked up the gun. She went to the window, gun pointing down, glanced outside, then walked out the door.

Seconds later, a man came in. Cadaverous, middle-aged, and dressed in a Nehru jacket, he looked around, smiled, and made his tentative way to the sushi bar.

“Excuse me,” he said to the sushi chef. “I’m Dr. Arthur Ostroot. I’m supposed to meet some people here with a TV show?”

“That’s us, honey,” Fredreeq called. “Sit down and have some edamame beans.”

Vaclav offered our expert some sake while Bing hauled himself up off the floor. He wobbled, glanced around the room, and steadied himself.

“Paul, what are we waiting for?” he yelled. “Next setup. And who’s got Vicodin?”

21

D

espite our director’s

stoicism, we wrapped early Monday night. Bing’s fingers swelled so badly he had trouble operating the camera, and he swilled so much sake to deal with the pain that he fell over backward into the sushi bar, enraging the chef. Joey wasn’t there to do her producer thing, soothing ruffled feathers and handing out twenty-dollar bills, so we were asked to leave.

Tuesday morning, Fredreeq called to say she and Joey were en route to my apartment. “To take you to an undisclosed location, in order to save your life. Wear running shoes. Dress sporty.”

These last five were words I’d never expected to hear from Fredreeq. My curiosity aroused, I was waiting on the curb when Joey’s Mercedes pulled up. “Is this about the guy who broke Bing’s fingers?” I said, climbing into the back seat.

“Indirectly,” Joey said.

“Absolutely,” Fredreeq said. “It came to us the exact same moment. Bing’s gun went flying and we both thought, ‘Krav Maga.’ ”

“Excuse me?”

Joey steered with her thigh and wrestled her red hair into a scrunchie. “I called Bing last night, but even drunk as a skunk, he wouldn’t say who the goatee guy was.”

“It’s obvious who he is. He’s blackmailing Bing.” Fredreeq pulled out a cell phone. “Keep talking. I just gotta call my kids.”

“Where’d you go last night?” I asked Joey.

“I tried to follow the goatee guy, just to see if I could. I couldn’t. I don’t even know when I lost him, because I followed what I thought was his truck all the way to Inglewood. I did get his license, though, right at the beginning.”

“The goatee guy,” Fredreeq said, putting away her cell phone, “works for Savannah Brook. Or organized crime in Vegas. He’s our saboteur. He’s the messenger, and here’s the message: Make sure Savannah Brook wins this contest or we make someone disappear. Annika, Wollie, Kimberly—”

Joey said, “That is the wackiest theory I’ve ever heard.”

“Wacky?” Fredreeq said. “You two ever hear of Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding? Did I make that up? Did Pete Rose bet on baseball?”

“So what is this undisclosed location?” I asked. “We’re not going to buy an attack dog or dye my hair or—”

“Dye your hair?” Fredreeq turned around in the front seat to stare at me. “Are you drunk? Women in this town run to their colorists every six weeks to get that shade of blond. We just told you. Krav Maga.”

“Yes, but what is it?”

“Hebrew,” she said. “Very trendy.”

“A deli?” I said.

“Much more fun than that.” Joey zoomed across Sepulveda. “A martial art.”

Uh-oh. “Is this something we’re going to watch?”

“Nope,” Joey said. “It’s something we’re going to do.”

“But I don’t want to do this. This is not something I’d like doing.”

“It’s very hip,” Fredreeq said. “It’s more martial than art, so you don’t have to learn calligraphy and eat seaweed and wear those white pajamas.” She, I now noticed, was wearing tight, rainbow-colored workout clothes. “In less time than it takes to get your teeth capped, they turn you into a killing machine.”

I didn’t want to become a killing machine. I articulated this as clearly as I could, but my friends were unmoved. My life was at stake, Fredreeq said. Was I or wasn’t I being stalked? Forget getting myself a gun. Had a gun helped Bing? Or Annika?

This would give me confidence, Joey said; I owed it to myself to give it a try.

I expected a low-ceilinged, mildewy room, because an old boyfriend had taken karate in a place like that, but Krav Maga shared the ground floor of the City National Bank building, and maybe the bank’s decorator and cleaning service. It was an aesthetically pleasing space, with a small boutique near the front, displaying, among other things, Krav Maga baby T-shirts.

Three people worked behind the desk, one more cheerful than the next. “Excessively happy people signify cult activities,” I whispered to Joey. A lovely girl introduced herself as Taffy, checked us in, had us sign a waiver in case we were maimed during the introductory class, and handed us three pairs of leather gloves.

“Not me. Sciatica,” Fredreeq said, indicating her lower back. “I’m just here for moral support.”

Taffy nodded and explained that the free introductory classes were usually held on Saturdays, but one had been added this week due to a sudden holiday demand.

“Are people anticipating a Thanksgiving crime wave?” I asked.

“Exactly.” Taffy smiled, immune to sarcasm. “The Orange County ATM thieves.”

“But this is a Jewish organization?” I asked, growing crankier by the minute. “And you work on the Sabbath?”

“Imi, our founder, was Jewish, but we’re open to everyone. I’m Presbyterian. And we train seven days a week, because criminals work seven days a week. This way!” She came out from behind her desk and led us through a lobby surrounded by workout rooms. The workout rooms had windows for walls, enabling us to see the people within, red-faced, dripping with sweat, punching bags with rigorous intensity. One man had strange headgear on. A woman’s knees were bandaged. No one was smiling. “Level two,” Taffy said, pointing. “And over there is Fight.”

And this was supposed to sell us on the program? What kind of people enjoyed watching other people suffer?

Joey. She was salivating, a diabetic looking into a bakery. Fredreeq inspected the lobby, pointing out vending machines, a TV suspended from the ceiling, and walls covered with photographs, magazine covers, and articles featuring testimonials from movie stars and cops. “Tasteful,” Fredreeq said. “Like the first-class lounge at the airport.”

Taffy pointed to the locker rooms and sent us on our way.

I expected our instructor to be some Special Forces type from the Israeli army, but again, they outmaneuvered me. Ten of us, all sizes, shapes, and ages, stood around, looking mostly uncomfortable, and at 8:47, a lanky guy disengaged himself from a trio of teenage girls, walked to the front of the room, popped a CD into a player, and introduced himself as Seth.

Seth had shaggy hair obscuring puppy eyes, and the energy level of someone who’d woken suddenly out of a sound sleep to find himself in the front of this room. He pressed a button and soft, alternative rock music massaged our ears. In a self-deprecating voice, Seth rattled off his résumé: a couple of black belts, in karate, Tae Kwon Do, Ho Chi Minh—I lost track. Then he pulled off his worn sweatshirt to reveal a tank top underneath, which in turn revealed a torso like the ones you see on late-night TV, belonging to guys selling exercise equipment. He told us about Imi Lichtenfeld, the guy who’d come up with Krav Maga, and demonstrated the martial art’s only formality, the bow, accompanied by some word that meant, in some language or other, “bow.”

“Ordinarily, we’d turn to the back of the room, to Imi’s photo, but there doesn’t seem to be one in this room, so, uh—” Seth smiled sheepishly. “Okay, just bow to me.”

I decided this wasn’t so bad after all, that it was, in fact, a cute sort of martial art, with cute bows, a cute instructor, and a founder with the cute little name of Imi.

Then the music changed.

Heavy metal took over as we jumped, jogged, kicked, punched, hopped, yelled, hammered, elbowed, kneed, ducked, and weaved ourselves into a frenzy. This explained the waivers. Seth, his sleepiness gone, egged us on. Periodically, he yelled “Time!” and let us sit, panting like dogs, as he demonstrated antimugging techniques. He attacked a punching bag with such force that the heavy bag flopped around like a balloon, decimating any doubts I’d had about his teaching credentials.

“Best targets? Crotch, neck, soft parts of the face. Knees. Eyes.” He smiled apologetically. “Some people get a little squeamish about eye gouging. But look: if you see an opening, don’t waste it on someone’s arm or their abs—a guy’s in good shape, he might not even feel it. Maybe you only get one shot. Maybe he’s got a knife. Maybe there’s three of them and one of you. Do the math. Make it count.”

I hate it when people say “do the math.” I didn’t want to do math. I didn’t want to do this. I wanted to go paint frogs.

I glanced in the mirror. My face was tomato red, my bangs sticking out, stiff with sweat and last night’s hairspray. I’d worn two jogging bras to keep my breasts from having a life of their own. I didn’t have the physique for this. I didn’t have the physique for any sport except wet T-shirt contests.

Joey was another story. Built like a skinny fifteen-year-old, she was in her element. She caught my eye in the mirror and winked.

“Defense and counterattack,” Seth said, “are peanut butter and jelly. Self-defense without counterattack gets you killed, if you’re dealing with someone bigger, or someone with a stick, screwdriver, handgun . . .”

Screwdrivers? People were out there with screwdrivers?

“The main thing is, you don’t give up,” Seth said. “If you walk away with nothing else from today, take this: worst thing you can do is curl up in a ball and quit. Don’t quit, don’t get in their car, keep screaming, keep fighting. I don’t care how scared you are or how bad you’re hurt. If you’re not dead, you’re not done.”

“Is this great?” Joey bounced past in search of a towel. “Everything he talks about makes me think of sex.”

Before I could wonder about my friend’s carnal habits, we were back on the attack. Seth told me I was doing fine, I just needed to rotate my hips when I punched, but I knew what he meant was “You have no aptitude for this—I’ve seen houseplants in better shape.” Still, I appreciated his tact and, of course, his amazing muscles.

And then it was over. We bowed to Seth, Seth bowed to us, and I staggered into the locker room while Joey went to the front desk to sign up for a lifetime membership.

Twenty minutes later I found Fredreeq in the waiting area talking to a bald man who looked like he’d just been released from the state penitentiary. I was reading a testimonial letter on the wall when I heard him say, “Here she is now. Hey, Savannah!”

I looked up to see a petite woman in a baseball cap and a T-shirt that said “Contact Combat” hurry past the front desk. Even hearing her name, I needed a moment to place her as my fellow

B.C.

contestant, because I’d never seen her in the flesh.

Fredreeq hissed, flattening herself against a vending machine. Her tie-dyed spandex did not lend itself to inconspicuousness, and I didn’t understand the need for secrecy, but her paranoia was contagious. Obviously, she hadn’t expected Savannah to show up here. I looked for shelter.

Too late. Savannah raced across the lobby, cell phone to ear, and reached up to flick a switch on the television mounted on the wall. She was halfway between Fredreeq and me but paid no attention to either of us, or to the man who’d called her name. She stared at the TV and I stared too, at ads for cat food, allergy medication, and dental stain removers and, then, a Channel 4 Live late-breaking-news special report.

I knew him at once, the face smiling down at us, a face made for TV. Missing for forty-eight hours, the reporter said. Student at Pepperdine. Son of a congressman.

Rico Rodriguez.

His face disappeared, replaced by a couple in their mid-forties facing a barrage of cameras. The man looked familiar. Congressman Rodriguez, a journalist called him, asking a question I didn’t catch. The congressman nodded. “Richard was to drive home Sunday to join us on a family trip to Telluride for Thanksgiving. He spoke to his mother Saturday afternoon, confirming he’d be home for dinner. To our knowledge, that’s the last anyone’s heard from him.”

Another journalist asked a question, one that Channel 4 didn’t pick up, but it didn’t matter. The camera tightened on Mrs. Rodriguez, lovely, blond, anxious. Her answer came out softly. “His favorite. Linguine with clam sauce.”

His mother. A chill went up and down my spine, a feeling that had nothing to do with the shower I’d just taken, the wet hair dripping down my back. It was the sudden conviction I had that Mrs. Rodriguez would never make that particular meal again.

22

B

y eleven I’d

gone home, changed, and made it to Santa Monica College. I had yet to feel the happy effects of the astrological transit Mercury trine Saturn that Fredreeq had promised.

The first thing I’d done, from Krav Maga, was call Detective Cziemanski. If the cops hadn’t made a connection between the disappearance of Rico Rodriguez and the disappearance of his girlfriend Annika, I could save them time. Cziemanski didn’t answer, so I explained this to his voice mail. I told myself Rico’s plight could be good for Annika, focusing attention on her case, but this didn’t cheer me up. Seeing Rico’s mother on TV had been profoundly disturbing.

The last thing I needed was a math test, but postponing it didn’t make sense, so I braved the parking facility and trudged across campus to the Liberal Arts Building, only to find the assessment-test office closed. Doughnut break?

I walked to the cafeteria for a doughnut of my own and realized that if the police were really going to focus on Annika, things could get complicated. I rummaged through my backpack and found the number for Britta, the au pair from San Marino, and left a message on her host family’s machine. In the cafeteria, I tried Cziemanski again, and got lucky. He apologized for our last conversation, then got to the point. “Everyone’s heard about the Rodriguez case,” he said. “The senator’s son.”

“Congressman’s son,” I said. “He was dating Annika Glück.”

There was a pause. “Really?”

“Yes. I talked to Rico last week. He had no idea where Annika was and now he’s gone too, and that’s an awfully big coincidence, don’t you think?”

“It’s worth looking into,” he said. “I’ll put in a call to the detective on the case.”

“Why aren’t you the detective on the case? You’re Annika’s detective, and if it’s a—a serial disappearance, shouldn’t all the cases get the same detective?”

“First, Annika’s ‘case’ right now is a missing person’s report. Second, Rodriguez goes to Sheriff’s Department, not LAPD. Third, we don’t know they’re related; if they are, LASD may get both.”

“How come Rico’s is a case and Annika’s isn’t? Because his dad’s important?”

“No. That’s why it made the news. It’s a case because the kid’s Corvette was found at LAX twenty-four hours after he was supposed to be home for dinner.”

“That doesn’t sound so dire,” I said. “Maybe he made a detour to Tijuana.”

Another pause. “If he did, he left two grand in the glove compartment. And what looks to be his own blood all over the trunk.”

Oh. I’d missed that, back in my apartment, channel surfing. The case was on the local stations, but I’d caught only snippets, most featuring Rico’s father, John J. Rodriguez: John’s career as congressman, John’s business as an industrial developer, and John’s ex-model wife, Lauren. One reporter stood outside the Rodriguez’s multimillion-dollar home in Lost Hills. John and Lauren did not appear, but a Dalmatian was spotted on the front lawn, its identity confirmed as the family dog, Hero.

His own blood in the trunk of his car. I felt sick. I pushed aside my doughnut, wishing I’d eaten it before calling Cziemanski.

I was headed back to Liberal Arts when my attention was caught by a guy smiling as he walked toward me. I couldn’t place him, but I smiled back anyway, on general principle.

He stopped. “Wendy,” he said.

“No, uh—”

“Winnie.”

“It’s Wollie.”

“Troy.” He stuck out his hand, and we shook. “We met last month. Some coffee place in West Hollywood. I’m Annika’s friend. Well, her tutoree. Tutee. Whatever. And you’re her other one, right?

Alle meine Entchen?

”

“Um, I don’t speak German. Sorry.”

“Oh, okay, I’m a geek.” He gave me a quizzical look. “She wasn’t tutoring you?”

“In math, not German,” I said. “What was it you just said?”

“Oh.” He grinned. “This nursery-rhyme thing she made me memorize, to help with prepositions. I figured you’d know it too.”

Something nibbled at my memory banks. “How does it go?”

“Well, she told me not to try picking up German girls with it, they’d laugh at me.”

I smiled. “Why? What’s it mean?”

“Okay.” He smiled again, dimples showing. “

Alle meine Entchen—

that’s, uh, all my little duckies

—Schwimmen auf dem See, schwimmen auf dem See—

swimming in the sea, swimming in the sea

—Köpfchen in das Wasser, Schwänzchen in die Höh,

heads in the water, tails in the air. Okay, the plot’s weak, but you know what? It helped. I aced my German final. She’ll be so jazzed.

Bin ich nicht gut?

Hey, do you know, is she out of town?”

With a shake of the head, I told him what was going on, and watched his face fall.

“Disappeared? You’re kidding,” he said. “That is, like, so weird.”

“Yeah, it is weird.”

“Yeah.” He gazed off, clearly troubled. “The last time I saw her was right here. Well, there. In front of the bookstore. Man, you wanna know what’s

really

weird—” He stopped, looked at me, then at his watch. “Shit, eleven fifty-two? Shit! My psych teacher said one more late, it counts against my grade. Sorry, man—” He turned and took off at a lope.

“But—!”

“Can’t slow down,” he yelled over his shoulder.

I loped after him. I hate loping. It attracts stares. “Troy! Wait up!” I yelled. Also, I wasn’t in loping shape. Especially after Krav Maga.

Happily, Troy wasn’t in shape either. He slowed, I caught up with him, and we switched to racewalking. “Jeez,” he said. “Gotta get to . . . the gym . . . more.”

“Me too,” I said. “So what’s ‘really weird’ about Annika disappearing?”

He held up a hand, battling for breath. “Confidential.”

I said, “I already know she was looking for a lawyer, and a gun, that she worried about disappearing into the criminal justice system—”

He stopped. “No shit?”

I stopped too. Nodded.

“Okay, shit.” He was panting heavily. “Not good. I was the one who told her this could happen. This means—what? It means she did what I told her not to. Unless she’d done it already. You know, I’m pretty sure I shouldn’t talk about this.”

“Troy.” I fought for breath and patience. “I have no idea what you’re not talking about, but as I seem to be the only person in North America looking for her, anything you know—please. Please, please, please.”

Troy veered to the right, and I veered with him, still racewalking. We passed the facilities maintenance building. “Okay,” he said. “I told her about how my roommate’s brother in Chicago got in trouble with the Feds because he lent his cell phone to someone who was part of a drug deal that was going down. He disappeared—”

“The drug dealer?”

“No, my roommate’s brother. The Feds arrested him on conspiracy, and he didn’t get a phone call, so no one knew where he was. For, like, two weeks. Of course, he’s Iranian.”

“Your roommate’s brother?”

“My roommate too. Second generation. No accent whatsoever, and not even Moslem or Muslim or whatever, but they busted him anyway. He’s doing time now.”

“For conspiracy.” I was struggling to follow the story. “How’s this tie in to Annika?”

“Man, she’s German. The Feds totally have it in for Germans. And the French.”

“Why would she even come to their attention? She’s an au pair in Encino.”

Troy looked at me, then away. We’d reached an old, fairly ugly brick building. He took the stairs two at a time, and at the top grasped a railing to recover, breathing hard. Apparently he wasn’t here on an athletic scholarship. “She wouldn’t,” he said, “come to their attention. If she was smart. That’s what I told her.”

The conversation couldn’t have been less clear if it were in German. “Does this have to do with guns? Or drugs? Or a guy named Feynman?”

Troy said nothing. My heartbeat, already in the anaerobic range, beat faster. I could see him teetering on the fence: to tell or not to tell. He glanced inside the glass door of the building.

“Please, Troy,” I said. “I’m not the Feds, I’d never talk to the Feds, I’m practically a Socialist; heck, I’m a Communist. Well, in the area of universal health care.”

He looked at the people hurrying into the building, then back at me. “She wanted to know about—the drug scene on campus, how you’d score stuff. So I told her the thing with my roommate’s brother. I told her, Don’t even go there. Keep your nose clean.”

“What kind of drugs was she interested in scoring?”

“She said she was just asking, but why do you ask about them unless you want them, know what I mean?”

“Troy, what kind of drugs?”

He closed his eyes and sighed. “Euphoria.”

It was a

sister drug to Ecstasy, only a warmer, fuzzier trip, he said, a way more happy trip. As my knowledge of Ecstasy was limited, this was not really helpful. I remembered when you got ecstasy through transcendental meditation, when a rave was a good review, when euphoria was a guy you liked liking you back. How innocent I was. How ancient.

Troy hadn’t done Euphoria himself, he assured me, but it was the Next Big Thing. Very hard to get. U4. He drew the nickname in the air with his finger. And then he went to class.

And I went to my assessment test. The office was open. I put drug thoughts aside long enough to state my intention to a girl in capri pants and an SMC sweatshirt, who led me into a small room and set me up at a computer terminal.

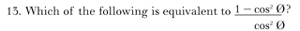

Fredreeq believed my stars were so aligned today as to make a multiple-choice test impossible to fail. I considered what Vaclav had suggested about religion, that mere belief conferred an advantage. Why not try to believe in astrology? I cleared my mind of its kaleidoscope of concerns and focused on the computer screen. Amazingly, I sailed through the first two levels of questions. Annika’s tutoring worked. I was exhilarated. Then came question thirteen.

What? I didn’t even understand the question. A buzzing sounded in my brain, a phenomenon that occurs when people talk to me about auto mechanics, computer programming, or compound interest rates. Next would come singing fairy voices and hummingbirds and bunnies cavorting in a meadow. My hand, taking on a life of its own, doodled on my notepad, copying the equation or whatever it was. I attached long sticky fingers to it, bulging eyes, some spots, and watched it turn into a greeting card: My Frog Ate My Brain.

Concentrate, Wollie,

I told myself. You’re a grown woman, you once operated a small business, you can set your VCR to record. How hard can this be, really?

I decided to pick the answer that looked prettiest: D. (csc

2

ø) - 1

The next problem, number 14, asked, “From a point on the ground the angle of elevation to a ledge on a building is 27 degrees, and the distance to the base of the building is 45 meters, blah, blah, blah” and had a diagram next to it that looked like either a treehouse or a club sandwich. I chose answer B, for Believe in the Stars. After that, I didn’t bother reading questions; I just went straight for the answers. This astrology thing either worked or it didn’t.

In this case, it didn’t.

I headed to

Rex and Tricia’s Mansion, fully depressed. Having flunked the assessment test, I was now doomed to take Maths 81 through 21, a course at a time, followed by endless science classes, which would keep me on SMC’s grubby campus until menopause set in.

At a standstill on the 405 North, I dialed Britta again, and this time she answered the phone. She couldn’t see me after three

P.M.,

as personal visitors were forbidden when she was working. With difficulty, I persuaded her to see me in the next hour, while her charges were still in school. Tricia’s frogs would have to wait.

Britta once again showed me to the kitchen, same table, same seat, same place mat. I was hoping she’d offer coffee or tea, after the hour-and-a-half drive I’d survived, but none was forthcoming. She sat opposite me, displaying the hospitality of someone facing a tax audit. I handed her the application page I’d been puzzling over, the one marked

Führungszeugnis.

Before I could ask, her face told me she knew what it was. She looked happy.

“You recognize this?” I asked.

“

Ja.

The

Führungszeugnis.

It is the paper that states you are not in trouble with police.”

“Is there anything strange about it?”

Her finger went to the date, prominently circled in red. “It is old.”

“Did you have to get the same document for your application?”

“Ja,

but mine is new, not even one year past.”

“So what do you think of that?” I asked. “Why would Annika’s be so old?”

“Perhaps, if Annika has some trouble with the police in Germany, and she knows the agency will not take her, and she wants to be an au pair in United States, and she has a

Führungszeugnis

from a different year, before she was in trouble, this is what she uses to make the application. And no one has noticed this, so she is allowed to come, and find a good family and has a car for her own use, because she is so lucky.”

I stared. “Annika told you all this?”

Now Britta looked confused, her eyes darting to the left as a hand went to her throat, to play with her necklace. “Told me?”