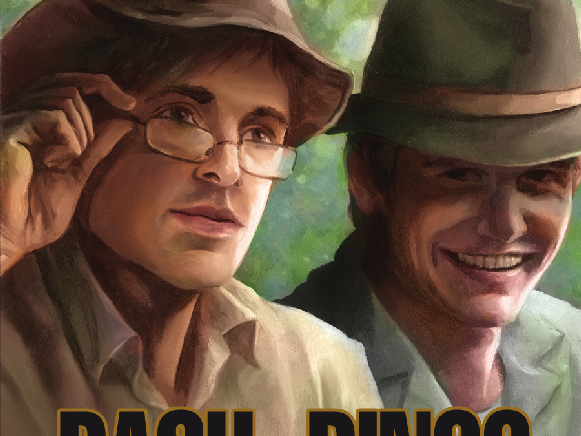

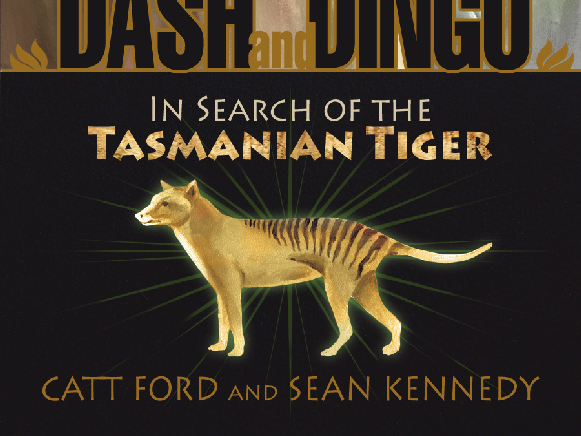

Dash and Dingo

Authors: Catt Ford,Sean Kennedy

Published by

Dreamspinner Press

4760 Preston Road

Suite 244-149

Frisco, TX 75034

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Dash and Dingo

Copyright © 2009 by Catt Ford and Sean Kennedy

Cover Art by Paul Richmond paulrichmondstudio.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Dreamspinner Press, 4760 Preston Road, Suite 244-149, Frisco, TX 75034

http://www.dreamspinnerpress.com/

ISBN: 978-1-61581-066-6

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

September, 2009

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61581-067-3

To all those who dream of adventure

and believe in the impossible,

even when the evidence

speaks to the contrary.

When the stars threw down their spears,

And watered heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger! Tyger! burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

—William Blake

One of the problems of writing something set in a time different from your own is that you have to pay attention to and reflect the sensibilities of that period. This includes the use of certain terms that have become “loaded” since then. In the case of

Dash and Dingo

, we have used the word “Aborigine” and other derogatory terms to refer to the native people as it was in Australia’s past. In contemporary society many indigenous people of Australia find the word offensive as it is linked to colonization and the injustices that were inflicted upon them, the ramifications of which are still found today. Although Henry and Dingo display attitudes that may have been revolutionary for the time, although they were not alone in them, they still would have been unaware of the future weight of the word.

The last known thylacine, which died in the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart in 1936, was known as Benjamin. Despite the name, however, there are many conflicting reports as to the proper sex of the tiger. We had to choose one for the purposes of our story, and we have elected to make Benjamin female.

—C.F. and S.K.

Dash and Dingo: In Search of the Tasmanian Tiger | 1

“DINGO!

NO!”

The wall of water was upon them so quickly that Henry barely had time

to jump clear with Dingo’s pack. The compression of the walls of rock

upstream released just as the river reached their clearing, making the water

surge past them at breakneck speed.

Dingo made a snatch for the heavy bag, overbalanced, and fell into the

angry river, disappearing into the yellowish dirty foam.

“You fucking thrillseeker,” Henry growled. He took off his glasses and

folded the temple pieces, hanging them carefully on a branch of a nearby tree

before he threw himself into the racing water without hesitation, kicking

strongly for where he saw the blur of Dingo’s sandy head bobbing.

It took only seconds for the water to swallow him up as well.

2 | Catt Ford and Sean Kennedy

The light falling across the pile of books and loose papers on his desk suddenly made Henry Percival-Smythe aware that it was far later in the morning than he thought it was. He frowned and almost knocked over the cup of tea that Hill had brought in for him what seemed like only moments before—but one sip of the now ice-cold contents of the cup proved that it must have been hours ago.

He made a face at the excessive tannin that now sat in the cup where fresh tea once had been. Henry removed his glasses and rubbed at the bridge of his nose. He gave the glasses a good wipe, so he could return to reading the documents spread out before him. But first he rang for Hill and requested a new pot of tea. Hill was duly unimpressed with the fact that the previous pot had gone to waste, but Henry didn’t notice as he had already returned to the small packet of photographs that had been wedged inside a field journal.

It was a magnificent creature. It was also the strangest, almost unimaginable, creature that you could have ever seen. And it had Henry enthralled.

“Are you looking at those again, sir?”

Henry almost jumped; he was so surprised by Hill’s sudden

reappearance at his side. The manservant to the department carefully made some room on Henry’s desk where he could place the tray bearing the teapot, milk and sugar jugs, cup, and strainer.

“It’s the thylacine, Hill.”

Hill gave the pictures a cursory glance and then turned back to the more important subject of his own sphere. “Would you like me to pour for you, sir?”

“Please, Hill.” Henry pulled out one of the larger photographs and tried to coax some interest from the other man. “Of course, it’s also commonly

Dash and Dingo: In Search of the Tasmanian Tiger | 3

known as the Tasmanian Tiger or the Tasmanian Wolf. But they’re misnomers, of course. It is actually a marsupial.”

“One or two sugars?”

“One, please. It’s perhaps the strangest animal to come out of Australia, and that’s saying something because

all

of their animals are unique and bizarre.”

“Lemon or milk?”

“Milk,” Henry sighed. As usual, it was an uphill battle to try and get anybody interested in his own private obsession. “It’s a sad story, Hill. The thylacine has been hunted until now it stands on the edge of extinction.

Besides a few disputed local sightings, the only place you can really see one alive now is in a handful of zoos around the world.”

“Here you go, sir.” Hill pointedly handed him the cup, so Henry was forced to recognize its existence. “Anything else?”

Henry shook his head despondently, and Hill nodded before leaving the room.

The photographs captivated him again, and Henry laid the cup of tea aside without having taken a sip.

There was something about the tiger’s outlandish appearance that charmed Henry and made it truly beautiful in his eyes. Sadly, the last thylacine in captivity in a London zoo had died in 1931, before he had formed his obsession. Henry had only seen black and white photographs and jerky film footage of it, but he knew the tiger to have a caramel-colored coat with distinctive dark brown stripes that wrapped around its back and a tail as stiff as a broomstick which usually jutted out at an angle from its body. It could also be mistaken for a strange dog until it opened its most enthralling feature: the mouth. The gaping jaws opened like that of an alligator; some of the photos Henry owned of it yawning could still send a shiver through him. The thylacine was a miracle.