Darwin's Blade (17 page)

Authors: Dan Simmons

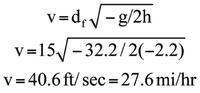

Which is consistent with the earlier skid analysis,” said Dar.

“So she actually hit him doing about twenty-seven miles per hour, braking from a top speed of almost fifty-six miles per hour,” said Syd.

“Fifty-five point seven,” agreed Dar.

“And he flew backwards seventy-two feet from the point of impact, coming to rest on his back with his head farthest from the van,” continued the chief investigator.

“As ninety-nine-plus percent of pedestrians hit straight on by such a van would,” said Dar. “That's why Larry and I knew that foul play was involved as soon as we saw the officer's photographs.” He tapped at keys until the equations disappeared from the screen and the original animated street scene returned. Another tap got rid of all the numerical values of lighting, curb height, skid length, and so forth.

Two male figures stepped out of the building. The van screeched around the corner from Fountain Boulevard and began accelerating madly down Marlboro Avenue. One of the men pushed the other man, who stumbled into the street, almost fell, and then righted himself just as the skidding van slammed into him. The body flew a long distance, landed on its back, and skidded farther, finally coming to a stop. The van pulled away and accelerated around the corner of the next intersection, cutting off a Ford Taurus that stopped. A man got out, knelt by the victim, and then ran west, disappearing around the corner to go to his friend's apartment to call 911.

“We found blood, hair, and brain matter on the right wheel, the hub of the right wheel, the front transaxle, the shocks, and on part of the catalytic converter of the van,” said Dar tonelessly.

In the animation, the van comes around the corner from Fountain Boulevard again, slows as it approaches the supine figure in the highway, then drives over it and backs up, dragging the body almost half the distance it had been thrown from the initial impact. Finally the body scrapes free, head pointed to the east, toward the van, as the rented vehicle continues to back up onto its own skid marks and finally comes to a stop.

“She had to finish the job,” said Syd.

Dar nodded.

“What did the jury have to say when they saw this animation?” asked the chief investigator.

Dar smiled. “No jury. No trial. I showed this to Detective Ventura as well as to the Accident Investigations people, but no one was interested. By this time, Donald and Gennie had dropped their lawsuit against the owner of the apartment buildingâI think it was because I confronted them with the light-meter readingsâand settled with the van rental people for fifteen thousand dollars.”

Syd shifted in her chair and stared at Dar. “You have absolute proof that these two killed Richard Kodiak and the LAPD dropped it.”

“They said it was just another fag killing, âanother garden-variety

homo

cide,' to quote the venerable Detective Ventura,” said Dar.

“I always thought that Ventura was an ass,” said Syd. “Now I know.”

Dar nodded, chewed his lip, and looked at the animation repeating itself on the screen. The human figure was hit, hurled, the van drove away, returned, drove over it againâdragging it back toward the front vestibule of the building, crushing the skull. The animation began again with two male figures, featureless, emerging from the well-lighted lobbyâ¦

“Lawrence's clientsâ¦the rental peopleâ¦were happy to settle for the fifteen grand,” he began.

“Wait a minute,” said Syd. “Wait a minute.” She went over to her big leather tote bag and pulled a top-of-the-line Apple PowerBook from it.

As she set the computer up on the table next to Dar's PC equipment, he looked at her dubiously, the way a Lutheran would have regarded a Catholic in the seventeenth century. Apple people and PC people rarely mix well.

Syd brought her computer to life. “Gennie Smiley,” she repeated. “Donald Borden. Richard Kodiak. These names ring a bell⦔

Columns of data flowed down her portable screen. She hurriedly typed in a search command. “Ahh,” she said, typed again, watched data whirl by and stop again. “Ahah!” she said.

“I like âAhah!' ” said Dar. “What?”

“Did you and Lawrence check into the backgrounds of these threeâ¦lovers?” asked Syd.

“Sure we did,” said Dar. “As much as we could without treading on Detective Ventura's toes. It was his case. We found that the victimâMr. Richard Kodiakâhad three addresses in addition to the Rancho la Bonita residence given on his driver's license: all in Californiaâone in East L.A., one in Encinitas, and one in Poway. Tracing his social security number, we found his listed employment as CALSURMED with no address. In old telephone listings, Trudy found a California Sure-Med listed in Poway, but the business is no longer in existence and all information regarding it has been purged from city records. Then we checked with the Poway post office and found that the Poway address was the same as that listed for the CALSURMED businessâbox number 616840. We suggested to the Accident Investigation team and Detective Ventura that they check with the Los Angeles and San Diego counties' Fictitious Business Filings under both the subject's name and the CALSURMED and California Sure-Med listings. They never followed up.”

Syd was grinning at her computer screen. “You know those red pins on my map?”

“The fatal swoop-and-squats?” said Dar. “Yeah?”

“California Sure-Med was the health provider for six of the victims. A certain Dr. Richard Karnak was instrumental in testifying in the liability cases.”

“You think Richard Karnak equals Dickie Kodiak?”

“I don't have to guess,” said Syd. “Do you have a photo of the victim? When he was alive, I mean?”

Dar fumbled through the file and came up with a small passport photo labeled

KODIAK, RICHARD R.

Syd had tapped keys, and a high-resolution black-and-white photo filled a third of her PowerBook's screen. It was the same photograph.

“And Donald Borden?” said Dar.

“Alias Daryl Borges, alias Don Blake,” said Syd, calling up a photograph and data column on the other man. “Eight priorsâfive for fraud, three for assault and battery.” She looked at Dar and her eyes were bright. “Mr. Borges was a member of an East L.A. gang until he was twenty-eight, but now he works for an attorneyâ¦a certain Jorgé Murphy Esposito.”

“Shit,” Dar said delightedly. “And Gennie Smiley. That has to be fake.”

“Nope,” said Syd, looking at another column of data. “But it wasn't her current legal name, either. She was married seven years ago.”

“Gennie Borges?” guessed Dar.

“SÃ,”

said Syd, and her grin grew broader. “But Smiley was an earlier married nameâ¦married briefly to a Mr. Ken Smiley who died in a car accident seven years ago. Can you guess her maiden name?”

Dar looked at Syd for a quiet minute.

“Gennie Esposito,” said Syd at last. “Sister to the ubiquitous attorney.”

Dar looked back at his screen where the van continued hitting the pedestrian, accelerating away out of sight into the night, and then returning to run over the poor man againâ¦and again.

“They know I know this,” muttered Dar. “But for some reason they felt threatened by me.”

“It

is

murder,” said Syd.

Dar shook his head. “The LAPD had already passed on the whole matterâ¦the rental people settledâ¦Donnie and Gennie moved to San Francisco. No one was interested. It has to be something else.”

“Whatever else it is,” said Syd, “it points directly at our Attorney Esposito. But there's something even more interesting here.” She tapped at her computer keys.

Dar caught a glimpse of the PowerBook's screen as the FBI symbol appeared, an asterisk password was typed, and directories, data, and photographs began flashing by.

“You can access the FBI data banks?” said Dar, surprised. Even exâspecial agents did not reserve that privilege.

“I'm officially working with the National Insurance Crime Bureau,” said Syd. “You know, Jeanette from Dickweed's meetingâher group. It merged with the Insurance Crime Prevention Institute in 1992, and to show its support, the FBI gives the NICB full access to its computer files.”

“That must come in handy,” said Dar.

“Right now it does,” said Syd, pointing to the photograph and fingerprint ID of the late Dickie Kodiak, a.k.a. Dr. Richard Karnak, original legal nameâRichard Trace.

“Richard Trace?” said Dar.

“Son of Dallas Trace,” said Syd, tapping more keys and looking at more data.

Dar blinked twice. “Dallas Trace? The big-time, good-old-boy lawyer? The guy in the buckskin vest and bolo tie and long hair who has that stupid legal show on CNN?”

“The same,” said Syd. “Next to Johnnie Cochran, America's best-known and most-loved defense attorney.”

“Bullshit,” said Dar. “Dallas Trace is an arrogant twit. He wins trials with the same tricks that Cochran used in the O.J. trial. And he has a book outâ

How to Convince Anyone of Almost Anything

âbut he couldn't convince me to read it in a thousand years.”

“Nonetheless,” said Syd, “it was his son Richard who was run over and killedâmurderedâin your Kodiak-Borden-Smiley van accident.”

“We need to get started on this,” said Dar.

“We just

did

get started,” said Syd. “The murder attempt on you and my investigation into the fraud-business gang wars are now on the same track. Monday we'll move ahead on it.”

“Monday?” said Dar, shocked. “But it's only

Saturday

afternoon.”

“And I haven't had a goddamned weekend off in seven months,” snapped Syd, her eyes fierce.

“I want one more day off and one more night to sleep in the sheep wagon before this goes any further.”

Dar held both palms up. “It's been a long time since I've had even a Sunday off.”

“Agreed then?” she said.

“Agreed,” Dar said, and held out his hand to shake hers.

She reached up, pulled his face closer to hers, and kissed him firmly, slowly, surely, on the lips. Then she went to the door.

“I'm going to take a nap, but when I come back this evening, I expect steaks to be grilling.”

Dar watched her leave, considered following her, considered kicking himself in the ass, and then drove into town to buy the steaks and some more beer.

D

ar pulled the lap belt tight and then tugged the shoulder straps snug as he settled into the L-33 Solo and moved the rudder pedals back and forth to make sure he was comfortable. Ken taxied the towplane forward a bit while his brother, Steve, stood watching the two-hundred-foot-long tow rope lose slack. Ken stopped for a moment. Steve looked over at Dar in the bubble cockpit of the L-33 and made a circular motion with his fist and thumb up, meaning “check controls.” Dar had checked them, and gave the thumbs-up signal for ready to go.

Steve caught his brother's eye in the towplane and swung his right hand low across his body from left to right. Ken pulled the tow rope taut and glanced back from the single-seater Cessna. Steve looked over at Dar again, who nodded, his right hand comfortably loose on the stick, his left hand on his knee but ready to grab the tow-hook release knob at the first sign of trouble. The towplane began its roll-out and the sailplane jerked slightly and began to bump along behind it off the grass and then down the asphalt runway.

Dar went back through his A-B-C-C-C-D checklist again as he rolled toward takeoff speed: Altimeter, Belts, Controls, Canopy, Cable, Direction. Everything all right. He shifted slightly to get more comfortable. Besides his lap belt and shoulder straps, he was strapped into a model 305 Strong Para-Cushion Chair parachuteâthe integrated seat pad putting something between his butt and the metal seat, and the inflatable air bladders along the back of the chute giving him much better back support than the upright strip of metal offered by the plane's seat. Most sailplane pilots of Dar's acquaintance disdained parachutes, but two of those he'd known had died for the lack of them: one in a totally foolish midair collision above Mount Palomar a few miles to the north, and the other in a highly improbable accident doing loops in his high-performance glider when the left wing simply detached.

Dar liked both the physical comfort of the integrated chute seat under him and the mental comfort of having the chute aboard.

The sailplane left the ground before the towplane, of course, and Dar held it a firm six feet above the runway until Ken got the Cessna airborne in a few hundred feet, and then Dar expertly put the L-33 in the normal “high tow” position, staying just about level with Ken's little Cessna and just above the towplane's wake. Officially, Dar was using a standard mountain-country technique of keeping his glider aligned properly with the towplaneâthat is, keeping the towplane at a fixed position on his windshield just above the sailplane's simple instrument consoleâbut in truth he was using the skilled pilot's trick of just placing himself where he wanted to be in relationship to the towplane and staying there. This skill required a certain amount of precognition and telepathy, but after being aero-towed by Ken several hundred times, both those elements were there.

It was a beautiful morning with unlimited visibility, a gentle three-knot wind out of the west, and lovely thermals building in the foothills and mountains around the valley airstrip. But when they had gained a thousand feet of altitude, Dar could see a storm front far to the west. It would be moving in over the coast soon and would spoil the day's soaring within a few hours.

They climbed at a steady rate as the towplane turned north and then west, then continued climbing as the Cessna turned them back onto a northeasterly course, toward Mount Palomar and into the wind. At the prearranged altitude of two thousand feet, Dar let the tension on the towline grow taut so that Ken could feel the imminent release. Then Dar pulled the release knob twice, saw and felt the towrope go free, and banked into a right climbing turn as Ken dropped the Cessna into a steep left descent.

Then the L-33 was on its own, lifting into the thermals rising from the foothills and steep ridges north of the airfield, and Dar settled back to enjoy silence broken only by the lulling and informative rush of air over the metal wings and fuselage.

Â

Dar had awakened early that Sunday morning, prepared coffee, set out bagels, cereal, and a note for Syd, and was prepared to leave for the Warner Springs gliderport when Syd herself showed up at the door, dressed again in jeans with a red cotton shirt this day and a light khaki vest with many pockets. Her holster and pistol were on her belt under the vest.

“I was out for a walk,” she said. “Are you skipping out on me?”

“Yep,” Dar said, and explained.

“I'd love to go along.”

Dar hesitated. “It's boring just standing around the field waiting,” he said. “You'd have a better time hanging around here and reading the Sunday paperâ¦I can drive down to the junction and get it. They have a paper dispenser near the row of mailboxes.”

“Won't you let me fly with you?” she asked.

“No,” said Dar, hearing more harshness in the syllable than he had meant. “I mean, my sailplane is a one-seater.”

“I'd still like to go watch,” said Syd. “And remember, I'm not really your guest this weekend, I'm your bodyguard.”

So they rinsed a Thermos with hot water and filled it with coffee, put some bagels in a bag, drove back through the little town of Julian on Highway 78 and then turned north and west through canyons on Highway 79 before coming out into the broad valley at Warner Springs.

Syd was surprised at how small his sailplane was. “It's not much more than a pod, a boom, wings, and a tail,” she said as he unlashed the tie-down cords.

“You don't need much else for a sailplane,” he said.

“I thought they were called gliders,” said Syd.

“That too.”

She steadied one wing while he lifted the tail boom, and together they pushed the red-and-white sailplane out from the tie-down area onto the grassy berm of the airstrip. Ken, flying his Cessna towplane, was making frequent touchdowns, tying onto other gliders, and towing them skyward.

“It's light,” said Syd, moving the wing easily up and down. “But it's made of metal. I thought gliders were canvas over wood or something, like the old biplanes.”

“This is an L-33 Solo,” said Dar, “designed by Marian Meciar and manufactured at the LET factory in the Czech Republic. It's almost all aluminum alloy except for the fabric on the rudder part of the tail. It weighs only four hundred and seventy-eight pounds empty.”

“Do the Czechs make good glidersâ¦sailplanes?” asked Syd as Dar opened the cockpit and dropped the seat-cushion-parachute in place.

“With this one they sure did,” said Dar. “I had to sand down some original paint ridges that were creating a high drag knee in the polar at about fifty-nine kts, and this model does have a tendency to stall without any prestall warning buffet, but for someone with enough experience it's a nice craft.”

“How long have you been flying sailplanes?”

“About eleven years,” said Dar. “I began along the Front Range of Colorado and then bought this plane used when I moved out here.”

Syd opened her mouth to speak, hesitated the briefest of seconds, and said, “How much does a plane like this costâ¦if you don't mind my asking?”

Dar smiled at her. “It was a good value at $25,000. But that's not what you were going to ask. What?”

Syd looked at him a second. “I know you don't fly commercially. I thought that you hated flying.”

Dar had started his walk-around preflight inspection. “Uh-uh,” he said, not looking at the chief investigator. “I love flying. Let's just say that I don't like being a passenger in the air.”

Â

Now Dar turned back into the wind and climbed over the foothills below Mount Palomar. To his east he had seen Beauty Peak standing aloneâits summit at about his altitude of fifty-five hundred feetâand Toro Peak farther to the southeast, its lone cone several thousand feet higher. But it was the thermals from these lovely ridges and foothills that Dar was seeking.

The L-33, as with most sailplanes, had very little in the way of instrumentation and controls. Dar had the stick, tubular rudder pedals, a short handle for the spoiler and air brake controls, another handle to lower and lock the undercarriage, the large knob for tow rope release, and a small instrument panel with his altimeter, variometer, and airspeed indicator. The little sailplane had no radios or electronic navigation devices. Actually, the instrument that Dar used most commonly was the “yaw string”âa bit of colored string attached to the fuselage directly in front of the cockpit. That and familiarity with the sound of the wind over the wing and fuselage let him know his airspeed better than the instruments. Dar knew from experience that the ASI pitot on the fuselage nose that fed wind speed/velocity data to the airspeed indicator was fairly reliable, but that the two ASI static ports on the aft fuselage sides were not flush, so they registered airspeeds about 6 percent above what they actually were. As long as he knew this bias, he was safe enough. Mental arithmetic had never been a problem for Dar. Besides, the yaw string never lied to him.

Moving his head constantly to keep track of other gliders and powered aircraftâonly a few were visible far to the eastâDar sought out the thermals rising from east-facing foothill slopes, bare patches of rock, and even from the tile roofs of the clusters of homes below. Two thousand feet above him and closer to Mount Palomar, a large hawk circled lazily in its own massive thermal. A few clouds were floating on the east side of the mountains now, and Dar could see a foehn wall of heavy clouds piled on the western slope of Palomar, with some spilling over the summit. Farther west he could see tall, black nimbo and stratocumulus building as the storm came in across the coast. This did not worry him. His plan was to continue his elementary 270-degree looping climbs through the foothill thermals until he had at least a safe eight thousand feet of air beneath him, and then tackle the lift and sink areas on the leeward side of the big peaks. This was known as “wave soaring” and took a bit more experience and skill to do right than simple thermal soaring.

Dar worked the ridges, finding the stronger thermals on the sun-soaked slabs, climbing, and then swooping back to the east in places to come on the downwind side of the slope to use the venturi effect to lift and soar through the notches between lower peaks, then circling back for more thermal lift. Finding these anabatic lift points and east-slope thermals meant working within a hundred or two hundred feet of the steep slopesâsometimes much closer. The tall Douglas fir and ponderosa pine on those slopes seemed very near each time Dar lazily banked the L-33 to the right and up, the variometer showing the climb in feet per minute. Dar glanced back over his left shoulder as he crossed one of these ridges and saw three deer running silently along the ridgetop. The only sound in his universe was the soft lull of the wind over the canopy and aluminum fuselage. The morning sun was getting very hot and he slid open the small panels on the left and right of the Plexiglas,

feeling

the warm winds that were lifting him as well as sensing the slight drop in performance as the airflow over the canopy was disturbed.

Now Dar was clearing the last of the steep ridges before the serious mountains, necessarily coming at them from the downwind side so approaching with plenty of speed and extra altitude, always ready to bank hard and turn and run if the curl-over downdrafts were too heavy to handle. But each time he cleared the ridgeâsometimes only thirty or forty feet above the ridge of rock or pinnacles of pinesâand then gained lift for the next one. Finally he was west of the line of ridges and some six thousand feet above a valley floor, approaching the slopes of Palomar, crabbing the L-33 sideways into the strengthening winds, and planning his wave-lift approach. The obliging presence of some “lennies”âflying-saucer-shaped lenticular clouds which rose above the rotor effect in the trough of the wave beyond the leeward foehn gapâshowed him the crests of the lift-area waves by stacking lenticulars like so many dishes on a shelf.

Dar glanced over his shoulder before beginning a 270-turn to gain a bit more altitude and was shocked to see another high-performance sailplane approaching from above and to his right. Sailplanes did not like to fly in formationâmidair collisions were the most serious things glider pilots could faceâand for this one to be so close when there was so much good empty sky today was unusual. If not actually impolite.

The blue-and-white glider came closer and Dar immediately identified it as Steve's Twin Astirâa nice, high-performance, two-seater glider in which the airport owner gave rides and instruction. Then Dar recognized Syd in the front seat.

For a second, his response was irritation, but then he relaxed, loosening his hand on the stick. It was a beautiful day. If Syd wanted to go soaring, why not?

But Steve's Twin Astir was coming closer, rocking its wings as it came. The wing rocking was a signal during aero-tow to

release now!

but Dar had no idea what Steve was trying to say as the two sailplanes came abreast of each other, wingtips about thirty feet apart, both of them rising quickly on the next lift wave coming off Palomar.

Syd was gesturing. She held up her cell phone, pantomimed talking into it, and pointed back toward the Warner Springs valley.

Dar nodded. Steve peeled away first, gaining altitude over the foothills but making a beeline for the airfield. Dar followed a few hundred meters behind. Coming out of the hills over the wide valley, he followed the Twin Astir into the usual entry-leg point south of the Warner Springs airport, dropped farther back as the two aircraft entered the eastern downwind leg at about seven hundred feet above the ground, made the base-leg turn north at about four hundred feet of altitude, watched the Twin Astir touch down smoothly on the grass to the right of the asphalt strip, and set his aiming point for flare-out about 150 feet behind that.

The wind was gusting now, but Dar came in smoothly, keeping his airspeed steady during the final approach while watching the yaw string flutter and estimating his minimum stalling speed plus 50 percent plus half of the estimated wind velocity, now at about twelve knots.