Dark Palace (64 page)

Authors: Frank Moorhouse

He placed the towel on the time-worn armchair seat and then sat down again, nude, legs crossed.

He looked across at her. âNot impressed with this American air-conditioning.'

âDid we waste our lives at the League? All those words we wrote and spoke?'

âThere is no one to tell us whether we did or did not.'

âI've worked nearly all my life for something which

utterly

failed. And moreover, we no longer

exist

in the eyes of the world.'

âEdith, you have lived

fully

âthat's not affected by considerations of success or failure.'

âMaybe I didn't live fully,' she said, trying somehow to pass her mind's eye over her years at the League, catching odd cameos of meetings, speeches and arguments.

âOh yes, Edithâyou lived

fully

,' he said without hesitation. âYou did.'

In a quiet voice he then mentioned to her Haydn's

Farewell Symphony

where the members of the orchestra leave, one by one, until there are no instruments left. âRemember? It goes like this.'

He hummed the final bars to her, as he came over to her bed. He lay down beside her, naked, still humming, conducting with a finger.

In the dimness she could see his wry smile.

âOh God,' she said, putting her head on his chest.

They folded desperately into each other's arms.

âWhat do we do tomorrow?' she whispered.

âTomorrow?' He lay there in her arms, staring at the ceiling. âTomorrow, we find ourselves a place in this new world.'

âIs there a place for the likes of us?'

âWe will find a place.'

She took a deep breath. âNo. We will

make

ourselves a place.'

The Dinner for Lester

Sean Lester, the last Secretary-General of the League of Nations, waited at the California Hotel in San Francisco for a month but was never asked to speak to the newly formed United Nations.

Alexander Loveday, Director of the League's Financial, Economic, and Transit Section, with twenty-five years experience, was asked to speak only onceâon committee structure.

Seymour Jacklin, Treasurer of the League of Nations, and an Under Secretary-General, with twenty-five years experience, was permitted to speak to the conference for fifteen minutes.

Arthur Sweetser organised, and paid for, the only dinner given in San Francisco to honour the League delegation. It was attended by thirty-seven friends and former associates.

At the San Francisco Conference, fifty nations ratified the charter of the United Nations on 26 June, 1945.

In 1946, a final Assembly meeting of the League in Geneva formally dissolved the League of Nations and the Permanent Court of International Justice, and its property, including the Palais des Nations, in Geneva, was handed over to the United Nations.

The League of Nations ceased to exist formally on 18 April, 1946.

The Fate of the League Pavilion at the World's Fair

February 10, 1946

Dear Sweetser,

I have a somewhat faint recollection that during the early days of my coming to Princeton when you were a permanent resident here, you once mentioned that some League property was stored in the farm buildings near the Institute. I believe you mentioned a copper plate or something of the kind.

Unless I am dreaming would you be good enough to let me know exactly what the article is â¦

Â

Signed, P.G. Watterson, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey

Â

April 4, 1946

Dear Watterson,

The copper plate was from the League of Nations Pavilion at the World's Fair in 1939.

It measured two metres across and its circular lettering read: âPeace on earthâGood-will to men'.

Â

Signed: Arthur Sweetser

Languages

The official languages of the League of Nations were French and English and officers of the League were expected to be fluent in both.

Under Secretaries-General

In practice, the Under Secretaries-General of the League reflected the nationalities of the permanent members of the Council, consequently there was never a Swiss Under Secretary-General.

After 1932, one of the two Deputy Secretaries-General was drawn from outside the permanent members of Council.

Rationalism

Edith and her mentor, John Latham, were both members of the Rationalists' Association of Australia, which grew out of the parent organisation in the UK formed at the end of the nineteenth century.

In Melbourne, a Rationalist Association was formed in 1906, in Brisbane 1909, Sydney 1912, and Perth and Adelaide in 1918. Rationalists stated their position as the adoption of âthose mental attitudes which unreservedly accept the supremacy of reason' and aimed at establishing âa system of philosophy and ethics verifiable by experience and independent of all arbitrary assumptions or authority'. The Rationalist Association had no doctrinal tests for membership and included as members Julian Huxley, Somerset Maugham, Bertrand Russell, Arnold Bennett, Georges Clemenceau, Clarence Darrow, Sigmund Freud, J.B.S. Haldane, H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, Albert Einstein, Professor L. Susan Stebbing, Havelock Ellis and Professor V. Gordon Childe. They saw religion as their main opponent. The movement declined after World War 2.

The British Rationalists were responsible for the creation of The Thinker's Library.

Alger Hiss and the United Nations

Alger Hiss, a high ranking officer of the US State Department, played a role in all three of the wartime conferences which worked towards the formation of the United Nations charter (Dumbarton Oaks, Yalta and San Francisco). At San Francisco in 1945, Hiss acted as temporary Secretary-General of the UN.

After this, Hiss became the Director of the US Office of Special Political Affairs.

On 3 August, 1948 allegations were made by Whittaker Chambers, a senior editor of

Time

and a former member of an espionage group spying for the Soviet Union in Washington DC, that Hiss was a member of this same espionage group. Chambers claimed that Hiss had given Chambers classified State Department documents to be handed over to the Soviet Union.

These allegations were made before the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Chambers allegedly hid some filmstrips of the documents in question in a pumpkin on his farm, and the case was tagged the âPumpkin Papers'.

At his first trial in 1949, Hiss pleaded not guilty. In 1950, he was convicted of lying to a Federal Grand Jury by claiming that he had no knowledge of the documents.

Richard Nixon played a central role in the conviction of Hiss.

The Hiss trial was said to have fuelled McCarthyism in the US.

In its day, the case symbolised the leftâright political clashâleft-wing intellectuals against the right-wing McCarthyitesâand was one of those issues which, in the words of Theodore Draper, âseparated friends and divided families'.

At the time this book was being written, the most recent comprehensive account of the case was

Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case

, (updated from the original published in 1978) by Allan Weinstein, Random House, 1997. In this updated book, Weinstein, having looked at the records of the NKVD and other material from Russia and Hungary, has changed from supporting Hiss to being convinced of his guilt.

This is also the conclusion of John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr in their book

Venona: decoding Soviet espionage in America

, Yale University Press, 1999.

The Debacle of the League and the United States

The failure of the United States to join the League of Nations was a democratic debacle.

It came about by a tangled, confused and dismaying vote in the Senate in 1919 where, despite overwhelming support for US membership of the League among the senators, political tactics produced a majority vote which fell just short of the two-thirds required (49 for, 35 against), and US entry was frustrated.

The best minds of the Republican PartyâTaft, Hughes, Root, Hoover and Kelloggâsupported US entry, as did the Democratic Party led by President Wilson, one of the architects of the League, and as did the media, the business community and the trades unions.

The Bill for US entry was drafted by the Foreign Relations Committee of the Senate and, while supporting entry, contained reservations about membership which were to be passed on to the League Assembly for consideration after the US had joined. President Wilson thought that the reservations undermined the concept of the League and advised his supporters to vote against it. So paradoxically, the small minority who opposed the League combined with some of the outright supporters of the League to defeat the Bill.

From then on, despite public opinion surveys in favour of the US joining the League, and constant lobbying at all levels of government, the US never joined the League. It did, however, participate in many of the world conferences including the Disarmament Conference, and in many of the League technical and social programs.

American foundations, such as the Carnegie Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, and individuals contributed large sums of money to the League.

Winston Churchill, in his book

The Second World War

(Volume One), said, âNor can the United States escape the censure of history ⦠they simply gaped at the vast changes which were taking place in Europe ⦠If the influence of the United States had been exerted, it might have galvanised the French and British ⦠The League of Nations, battered though it had been, was still an august instrument which would have invested any challenge to the new Hitler war-menace with the sanction of International Law ⦠Americans merely shrugged their shoulders, so that in a few years they had to pour out the blood and treasure of the New World to save themselves from mortal danger.'

Intellectual Cooperation Section

Edith's friend, Jeanne, belonged to the the Intellectual Cooperation Section. The head office of this Section was in Paris but some officers were in Geneva and Rome. It coordinated the Educational Cinematographic Institute in Rome, and the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law, the Permanent Committee of Arts and Letters, the Advisory Committee on the Teaching of the Principles and Facts of Intellectual Cooperation, the Sub-Committee of Experts for the Instruction of Youth.

It planned to rewrite history books for schools and, by so doing, remove national bias.

It had 23 expert committees, and many of the world's leading scholars and artists served on these. With the setting of the United Nations this section evolved into UNESCO.

Kelen and Derso: Cartoonists of the LeagueâHard Times

Emery Kelen and his collaborator Derso were internationally renowned caricaturists in the days of the League of Nations.

In 1954 Derso wrote a letter to Arthur Sweetser: âI got your address from Albin Johnson; he told you about the drawing I want to sell and my hope that you might be interested. It is the most elaborate cartoon of the past Geneva scene and the finest watercolour to frame. By offering it for a modest fee, $150, I would like to see it in the hands of somebody who really could enjoy and appreciate it ⦠(t'was a puzzle for myself to remember and recognise the 150 people we drew in that single cartoon) ⦠I would appreciate very much if you'd be willing to pay this fee. I am now in bad shape and badly need some support of my old friends â¦'

Sweetser replied: â⦠The great difficulty, which I am sure you will appreciate, is the financial one. For almost two years now since my UN job came to its end, I have been without salary ⦠in addition we have had several sicknesses in the family which have necessitated heavy expenditures ⦠to be of what little help I can in your present difficulties, I am enclosing a check for the $150â¦'

Joseph Avenol

The events and interpretations surrounding the departure of the French Secretary-General of the League, Joseph Avenol, in 1940 will probably never be precisely clear.

In the chapters describing Joseph Avenol and the League, some compression has occurred but the course of events is fairly much as depicted.

The sources for the dramatisation of Avenol's last months as Secretary-General are as follows: James Barros,

Betrayal from Within

, Yale University Press, 1969; Sean Lester, typewritten diary, 1939â45, League of Nations Archive, Geneva; Thanassis Aghnides, âThe Reminiscences of Thanassis Aghnides', typewritten manuscript in Oral History Collection, Columbia University, Butler Library (researched for me by Joanna Murray-Smith) and in a second copy at League of Nations Archive, Geneva; Quai d'Orsay archives (researched by Xavier Hennekinne); Raymond B. Fosdick,

The League and the United Nations after Fifty Years

, self-published, 1972, Connecticut; Arthur Sweetser, personal papers, Library of Congress, Washington DC; and internal circulars and memoranda of the League Secretariat.

The Persecution of Homosexuals and Lesbians by the Nazis

The scholarly estimate of the number of homosexual men severely persecuted by the Nazis is around 50,000. The estimates for those who ended up in concentration camps vary between 20,000â30,000. More than half died there, according to Rudiger Lautmann's account in âThe Pink Triangle: the Persecution of Homosexual Males in the Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany', in Salvatore Licata and Robert Petersen (eds),

Historical Perspectives on Homosexuality

(New York, Haworth Press, 1981).

There were no special concentration camps for gays, but they were sent to camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald and Berlin-Sachsenhausen where they were beaten, starved or worked to death. Many also died in penal battalions of the German army.

There is no evidence that the Nazi regime set out to exterminate the homosexuals as they did the Jews. There were various attempts by the Nazis at âreeducating' and reorienting homosexuals and towards this end some suffered medical experimentation including castration.

Their concentration camp mortality was higher than any other of the

âanti-socials' in the camps (excluding the Jews)ânearly twice as high, say, than that of Jehovah's Witnesses (Rudiger Lautmann,

Gesellschaft und Homosexuality

, Frankfurt, Suhrkamp, 1977).

Homosexuals also suffered discrimination and violence from other concentration camp inmates, which reflected the anti-homosexual prejudices in national communities at large.

Of all the concentration camp prisoners, the effeminate homosexuals appeared to have suffered disproportionate ill-treatment.

After liberation of the camps in 1945, the homosexuals both from the West and the East were still liable to criminal prosecution under the new laws of the two parts of Germany. These laws were not reformed until 1969 and 1967 respectively.

There are also reports of lesbians being ill-treated and confined in concentration camps.

I am indebted to the late Peter Blazey and to Tim Herbert for early research advice on this subject and to Gerard Koskovich for his valuable annotated bibliography, âThe Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals' (

http://members.aol.com/dalembert/lgbt-history/nazi-biblio.html

).

The News About the Extermination of the Jews

Walter Laqueur, in his book

The Terrible Secret

(Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1980), says, âIt will be asked whether it really would have mattered if the world had accepted the facts of the mass murder earlier than it did. No one knows. Quite likely it would not have made much difference. The Jews inside Europe could not have escaped their fate ⦠Militarily, Germany was still very strong ⦠There were, however, ways and means to rescue some even then. They might or might not have succeeded, but they were not even tried. It was a double failure, first of comprehension and later of seizing the opportunities which still existed â¦'

Précis-Writers

The task of a précis-writer was to summarise accounts of meetings. They made notes during the debates and then dictated their summaries. This demanded a good deal of judgement. They had to reduce individual speeches to a fraction of their size and to discriminate between short but often important speeches and long but sometimes irrelevant speeches.

The vanity of delegates caused problems, as did the wish for some delegates to have their speeches recorded in full for use back home.

The League précis-writers over the years evolved a unique skill and after a while complaints were surprisingly rare.

James Joyce and the Secretary-General

James Joyce, when he was living in Zurich during the war, approached Sean Lester, Acting Secretary-General of the League of Nations, and asked for assistance in getting his daughter Lucia out of a hospital in France and into neutral Switzerland.

Lester went to see Joyce and tried to help but Joyce died before any arrangements could be made and Lucia remained in France until the end of the war.

Permanent Delegates

As the League went on, a number of member states established Permanent Delegates in Geneva, some with ambassadorial rank and staff with the role of informing their governments of League affairs and participating in committees. At most there were 34 Permanent Delegates.

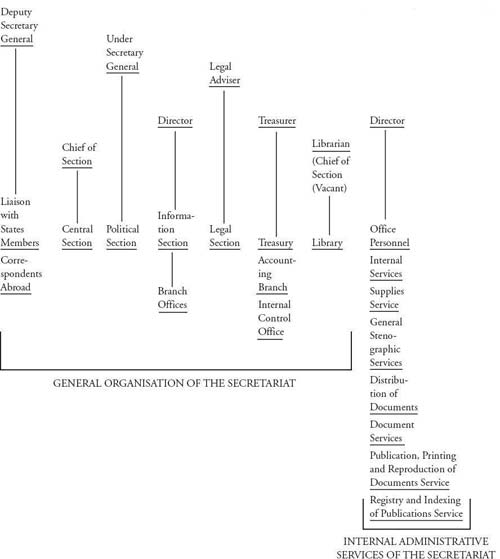

ORGANISATION OF THE SECRETARIATâ1938

Secretary-General (and Office)

Deputy Secretary-General (and Office)

Under Secretaries-General (and Office)

Attached to Principal Officer (Official with Rank of Director and Office)