Dark Continent: Europe's Twentieth Century (66 page)

Read Dark Continent: Europe's Twentieth Century Online

Authors: Mark Mazower

Tags: #Europe, #General, #History

The only visionaries meeting the challenge are the Europeanists clustered in Brussels, and the only vision offered is that of an ever-closer European union. Its acolytes still talk in the old way—as if history moves in one direction, leading inexorably from free trade to monetary union and eventually to political union too. The alternative they offer to this utopia is the chaos of a continent plunged back into the national rivalries of the past, dominated by Germany and threatened by war.

Dreams of perpetual peace have a long history in European thought, and emerged naturally once more out of the bloodletting of the mid-twentieth century. The desire in particular to staunch the Franco-German conflict which generated three wars in under a century played an important part in the formation of the Common Market. In earlier formulations, perpetual peace was to be secured in Europe through its very multiplicity of states. But the rise of the nation-state and the bloodshed it has provoked led, during and after the Second World War, to the view that the nation-state was itself a cause of wars. The ghosts of the past, however, offer a poor guide to the future: the fear of another continental war, and the associated pessimism in relation to the nation-state, need to be matched against the facts of the present situation and not merely taken as resting on self-evident truth. Stanley Hoffmann’s comment of some thirty years ago remains to the point: “An examination of the international implications of ‘nation-statehood’ today and yesterday is at least as important as the ritual attack on the nation-state.”

5

It is now clear that Europe’s twentieth century divides sharply into two halves. Before 1950, more than sixty million people died in wars or through state-sponsored violence; by contrast, the number of those who died in such a fashion after 1950 is well under one million, even taking the war in Yugoslavia into account. Thus if the nation-state is blamed for the bloodshed of the first half of the century, it should also be given some credit for the peaceful character of the second. After all, it is now clear that the nation-state has flourished in Europe right through the century, surviving the Nazis, and the Cold War too. Both the USA and the Soviet Union, in different ways, were forced to come to terms with the continuing resilience of their European allies. The Common Market itself started out as a series of negotiations among

nation-states and remained a forum for such negotiations for most of its life: only in the mid-1980s did the federalist impulse grow, largely because of French unease at growing German strength.

Yet the fear of Germany is a classic example of what happens when the past is projected into the future. Germany and Russia between them provided, it is true, liberal democracy’s two greatest threats this century, but they also suffered the highest death tolls of any European countries. The predominance of Germany remains the fundamental feature of the European power structure as it has done for a century, but Germany’s dreams of empire are gone—surviving only in nostalgic photo albums of pre-war Silesia or East Prussia. Its military caste has been destroyed, its minorities in eastern Europe are reduced to a remnant of the millions who constituted Hitler’s

casus belli

. Five million war dead weigh more heavily on German minds than all of Hitler’s triumphs. If German companies invest today in eastern Europe, it is not because they represent the vanguard of a Fourth Reich, but because they are capitalists, whose capital is as vital as ever to Europe’s economic health.

History seems even less likely to repeat itself with Russia. The country is smaller than at any time in the last two centuries, shorn of its Baltic states and the old western and southern Soviet republics. Internally, the collapse of communism has given rise to a kind of jungle capitalism, where massive fortunes are made alongside poverty unparalleled elsewhere in Europe. The desperate need for social reconstruction and the sad state of the Russian Army produce nationalism and a nostalgia for communism, but they also make irredentism and empire-building unlikely and risky eventualities. The Russian minorities who remain in the Baltic states are less of a threat to European stability than the decaying nuclear warheads and unsecured military installations left behind by the end of the Cold War.

The danger is that the West will not take this weakened Russia as seriously as it should. The EU, in particular, has given it paltry financial assistance—the contrast with American aid to western Europe after the Second World War is a depressing reminder of Europe’s inability to plan its own affairs with long-term vision. “Once we were great and now we are small,” runs a Danish school song, but it is not easy for a great power to adjust to imperial disengagement, especially

when there are no attractive alternatives such as the European colonial powers found in the Common Market.

Here, after all, has been the great change in the nation-state since the Second World War: cooperation has replaced competition. Imperial nation-states shed their colonies and found that they were unnecessary for their prosperity. Nuclear weapons rendered much older strategic thinking obsolete and made it harder to envisage war as part of national policy. Armies are getting smaller rather than larger, as conscripts are replaced by specialist professional forces. Borders are chiefly now a matter for police rather than the military: illegal immigrants are a greater concern than neighbouring armies. Minorities still exist but in far smaller numbers than before 1950: thanks to genocide, expulsion and assimilation, the chief cause of the Second World War has effectively disappeared. In all, Europe has entered a new era in which war, empire and land have all come to seem far less important for national well-being than they once did. As a result, population decline in Europe today evokes none of the frenzied panic about national virility, racial purity and military performance that it did in the 1930s, and is more likely to be discussed in terms of pension schemes and welfare reform. Most of Europe either is in or wishes to join the EU and NATO, a situation with no historical precedent. From today’s perspective, therefore, the “Europeanist” project seems to be based on unreal fears and expectations. Nation-states are as strong as ever and cannot be willed away. Nor need they be, since they pose no threat to continental peace.

Perhaps the European Union can most fruitfully be seen as the West European nation-state’s concession to capitalism. In other words, its existence is based on the recognition by its member states that national economic policies can no longer guarantee success, and that their prosperity lies in the kinds of cooperation and joint action made possible through the EU. This is why the EU remains most important as an economic entity; it is part of the attempt to adapt European capitalism to the needs of an increasingly global era.

But economics is not everything, and the globalization of capital does not mean that the nation-state is finished in Europe, as many argue today. The Italian Luciolli criticized the Nazi New Order for assuming that material goods were enough to create a feeling of

belonging among diverse European nationals, but his accusation could more fairly be levelled at the European Union, with its disquieting “democratic deficit.” The fact is that capitalism does not create feelings of belonging capable of rivalling the sense of allegiance felt by most people to the state in which they live. If anything, contemporary capitalism is destroying older class solidarities and making individuals feel more insecure, thus rendering other forms of collective identity more and more important. So capitalism requires the nation-state for non-economic as well as economic reasons, and will not further reduce its power. “Consciousness of the nation remains infinitely stronger than a sense of Europe,” wrote Raymond Aron in 1964. The same is true today, and the European Union is therefore likely to remain—in the words of a Belgian diplomat—“an economic giant, a political dwarf and a military worm.”

6

All this means that the current state of affairs in Europe is untidy and complicated and likely to remain so: there are more nation-states in Europe than ever before, cooperating in a variety of international organizations which include—in addition to the EU and NATO—the Council of Europe, the OSCE, the WEU and many others. The great era of nation-state autonomy is past, and the globalization of capital (and labour) forces countries to give up exclusive control of some areas of policy; but this Europe of overlapping sovereignties should not be confused for one in which nation-states are vanishing and disappearing into larger and larger entities. Europe’s great variety of cultures and traditions which was so prized by thinkers from Machiavelli onwards remains fundamental to understanding the continent today.

This panoply of national cultures, histories and values does make it hard for Europeans to act cohesively and swiftly in moments of crisis, though this hardly mattered in the Cold War as Europeans on both sides of the Iron Curtain surrendered the initiative over their affairs to the superpowers. For decades, they got into the habit of blaming the Americans and Russians while expecting them to sort out their affairs. But the war in Bosnia showed that even after the end of the Cold War, this habit has not died. None of the European organizations played anything other than a marginal role in the Yugoslav conflict. The year 1992 was supposed to herald the making of a new,

confident and unified Europe: the ethnic cleansing of the Drina valley that spring and summer showed this up for the windy rhetoric it was. Lack of a unified will, not objective circumstance, held back Europe from a decisive response in Bosnia, and its nation-states could not agree among themselves on a policy until they were forced into one by Washington.

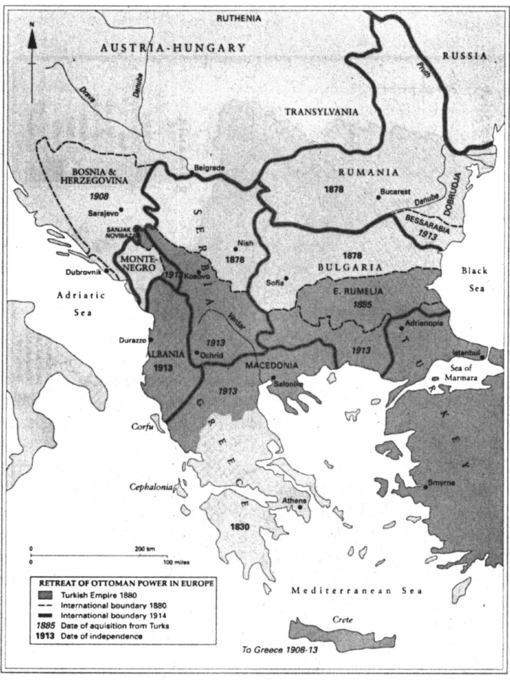

But although Europe’s refusal to take responsibility for its own affairs is not an edifying sight, perhaps it matters less than it once did. Were Bosnia the prelude to a new era of bloodshed in Europe, such indecision in the face of crisis might be alarming. The war in the former Yugoslavia, however, was not the start of a new era of ethnic conflict—at least in Europe—so much as the final stage in the working out of the First World War peace settlement, and the definitive collapse of federal solutions—in this case through communism—to minorities problems. Conflict is still imaginable in the Balkans and the Aegean, but can scarcely threaten continental peace. There is a good reason why the Yugoslav war of 1991–5 did not lead to a more general war while the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 did: today Europe’s major powers are partners with one another rather than military rivals.

Globally, Europe has lost its primacy, and perhaps that is what most Europeans find hardest to accept. Yet compared with other historical epochs and other parts of the world today, the inhabitants of the continent enjoy a remarkable combination of individual liberty, social solidarity and peace. As the century ends, the international outlook is more peaceful than at any time previously. If Europeans can give up their desperate desire to find a single workable definition of themselves and if they can accept a more modest place in the world, they may come to terms more easily with the diversity and dissension which will be as much their future as their past.