Damn His Blood (4 page)

Authors: Peter Moore

George Parker had been 30 years old when he first set foot in Oddingley. He was able, principled and worldly, still a bachelor and quite possibly an instant attraction for the eligible local ladies. There must have been every hope that the appointment, which constituted his second ecclesiastical post, would be successful and enduring. Yet it was a hope that soon faded. By the autumn of 1805 Parker was deeply unpopular with many in the parish. There had been sparks of violence and a succession of court cases with John Barnett of Pound Farm. Thomas Clewes from Netherwood had been heard damning his name in the Droitwich taverns, and as details of the poisonous quarrel seeped out into nearby parishes, it was said that opposition to Parker was led by Captain Evans of Church Farm. It was clear to all across the parish that the feud cut deep.

8

George Parker was not a native of Worcestershire. He was born to Thomas and Jane Parker at a farm in Johnby in the Lake District, hundreds of miles to the north of Oddingley. Thomas Parker is recorded as being ‘a respectable yeoman, of good connections’ and like many in the locality probably filled his fields with flocks of Herdwick and Rough Fell sheep, which were traded at the market in Penrith, seven miles away. George Parker was baptised at Greystoke Church on 26 June 1762 in the grassy shadows of the Lakeland Fells.

In the 1760s Thomas Parker and his young family were comfortably set in life. Whereas almost all of his peers leased their slices of the Cumberland hills from members of the old landed gentry, Parker held a considerable estate in his own name, something that was a clear source of independence and pride. A quirk of Parker’s acreage was that a portion lay detached from the rest, intermixed with fields belonging to the Duke of Norfolk and controlled by his son, the young Earl of Surrey, who lived just two miles from Johnby at Greystoke Castle. At some point around the year 1770 Thomas Parker had approached Surrey, proposing to reorganise these boundaries so that they could manage their estates more effectively. It proved an astute move. The result of the ensuing arrangement pleased Parker and Surrey so much that a friendship was formed. To further express his gratitude Surrey promised Thomas Parker that he would provide an education for his son George.

It was an unexpected twist that carried George Parker’s life on a new and exciting course. Supported by Surrey, he enrolled in the endowed grammar school at Blencow, just a mile and a half from his family home, where he studied history and the classics alongside the sons of gentlemen. Thereafter, George Parker’s bond with Surrey strengthened. The earl was an eccentric politicking Whig famed in high society for his disregard for social and hygienic niceties and for the ‘habitual slovenliness of his dress’. Among commoners, though, he was highly popular, a charismatic figure known for his ‘conviviality’ of spirit, his reformist tendencies and for being something of a provocateur. During the general election of 1774 he supported several local freemen who managed to dislodge the Carlisle parliamentary constituency from the powerful and fabulously wealthy Tory-leaning Lowther family. At the elections of 1780 and 1784 he was himself elected to Parliament, where he instantly joined Charles Fox in fierce opposition to the American war.

How precisely George Parker served the Howard family during these years is unclear, though one theory suggests he was engaged as Surrey’s election agent. This fact was later questioned, but it still appears the most plausible explanation. By nature George Parker was ambitious, persuasive and hard-working, traits which displayed themselves in subsequent years and would have served him well while scrambling through the thickets of an eighteenth-century general election campaign. Agents were sent out into the boroughs, charged with cajoling, harrying and pestering the freemen for votes, reminding them of their allegiances and distributing financial incentives when necessary. A trusted knot of energetic lobbyists would have been indispensable for Surrey, who did not just have to trouble himself with his own election campaigns in Carlisle, but also had to orchestrate others intended to plant favoured Whigs in Westminster from constituencies scattered about the country in places like Arundel, Leominster and Hereford. That the young Parker was duly dispatched to such distant outposts of the Howards’ vast estates would explain his taste for travel, something that may well have developed in these formative years.

Parker would have been an able candidate for the role. Having concluded his education at Blencow, it is difficult to envisage him returning to labour on the family farm. Rather, as young, erudite and at ease among the gentry, it seems more logical that he would be employed in a sphere where he might use his ability to write and reason. Crucially, too, Parker’s loyalty was beyond question. Since his earliest childhood he had been allied to Surrey: he had grown up with Greystoke Castle hidden, symbolically, just beyond the horizon; his family were dependent on the Howards for their social standing and now he was indebted to Surrey for his education. The young protégé was absorbed into his patron’s inner circle, and most accounts agree that it was a role in which he thrived. They declare that Parker carried out his duties with such cool reserve and careful professionalism that Surrey recalled his contribution for years after.

In the early 1780s George Parker’s life took its most significant turn. Perhaps fired by his travels and his own latent ambitions, he resolved to leave Cumberland and to journey south to the Midlands to study theology. This he did, and for several years afterwards he resided at St John’s Academy in Warwick, where he served as classical assistant. The move, however, did not mean a total splintering of his relationship with Surrey – who had now become the Duke of Norfolk following the death of his father in 1786. Indeed, the new duke lay behind Parker’s elevation to a curacy in Dorking, one of the Howard family’s parishes. Several years later Parker relocated yet again. It is unclear just what lured him to Oddingley. Perhaps it was the prospect of a sedate community and a reasonable income. Or he may have been tempted by its appealing location so close to Worcester Cathedral, a spiritual, intellectual and administrative centre of the Protestant Church.

As with Parker’s other appointments, the duke’s influence swirled like a current just beneath the surface. The opening at Oddingley came after Norfolk had appointed Reverend Samuel Commeline – Parker’s predecessor – to another of his parishes, at Hempsted just outside Gloucester. Commeline’s move left Oddingley temporarily vacant and enabled Norfolk to recommend Parker as a replacement to his parliamentary friend and fellow Whig, Lord Foley. It was a typical eighteenth-century transaction, and it concluded in May 1793, when Reverend Parker was presented to his new parishioners by Bishop Hurd of Worcester. George Parker’s unlikely rise from yeoman’s son to country parson was complete.

fn1

Settling into Oddingley in the summer of 1793 Parker had his best years before him, but to his new parishioners he was unknown and untried and he must have been acutely aware that he was an outsider. In this corner of England the locals spoke with a slow, sloping accent. ‘You’ was ‘thee’ or ‘yaw’. ‘Nothing’ was pronounced ‘nought’ and ‘i’ became ‘oi’. Vowels were short and stunted, leaving ‘sheep’ as ‘ship’, and the ‘h’ was often lost altogether giving ‘ighest’ and ‘ill’. Pitt the surveyor remarked that during his time in the district he experienced many other provincialisms: of these, he explained, ‘an occasional visitor can pick up but a few;

9

it requires long residence, and much colloquial intercourse with the middle and lower classes’. It was a new code to master, and one that Parker would never consider his own.

In the years before mass transportation, at least a generation before the railways, Parker’s northern roots, his accent and mannerisms, distinguished him from the other villagers like sand from stone. In the 1790s much of the population of rural Britain was born, raised, lived and died within a handful of miles. Until 1795 wandering vagrants could still be sent back to their home parishes if they were suspected of burdening the poor rate, a law which lent some credence to Adam Smith’s bleak observation that it was more difficult for them ‘to pass through the artificial boundaries of a parish

10

than the arm of the sea or a ridge of high mountains’. And while the poor were repelled, other newcomers were often tolerated uneasily.

Parker’s life in Oddingley began quietly but with steady purpose. His appointment signalled a change for the villagers, who had been so neglected in recent years by their political and spiritual masters. The records show that Reverend Commeline was an absentee clergyman, paying clerical deputies to conduct services on his behalf with a portion of his salary. In the years 1780–92 the signatures of five curates fill the pages of the parish marriage register while Commeline’s does not appear once. Only with Parker’s appointment in 1793 does stability settle on the records.

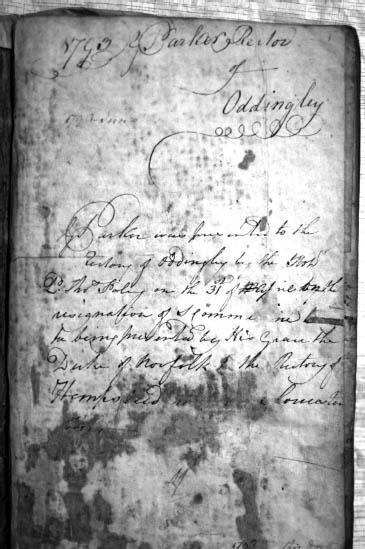

Parker’s ornate handwriting across the front of Oddingley’s parish records is one of the few tangible traces of his personality

The Oddingley marriage register comprises one of a tiny number of documents that record life in the parish in the last decade of the eighteenth century. It’s a world for the most part lost to history, and observing it at a distance of more than two centuries is like peering into a darkened room lit only by dim chinks of light. Even so, traces of the new Reverend Parker can be found in these frail records. It is clear that he devoted his time and attention to his new parish, his application shown by the fact that he conducted all the important services himself. Parker’s relish for the job is also suggested by an odd fragment in the marriage register. Hard against the top of the parchment at the front of the book a careful and florid hand has writter, ‘The Marriage Register of Oddingley, from 1756.’ Underneath, with the ardour of an aspiring professional or of a freshly appointed manager keenly marking his new territory, comes in carefully crafted letters: ‘G. Parker, Rector.’

Inside the calfskin cover of the other surviving parish register – a collection of notes tracking the Church’s business in the parish back into the middle of the seventeenth century – is a more definite sign of Parker. Here the quill begins with the same autograph: ‘G. Parker, Rector.’ The ink is thin and the P of Parker surrounded by dashing loops. Below is a sliver of autobiography, all composed in the third person with the characters slanting confidently to the left: ‘G. Parker was first invited to the rectory of Oddingley by the Ld Tho Foley on the 31 April on the resignation of S Commeline, he being presented by his Grace the Duke of Norfolk to the rectory of Hempstead, Gloucester.’

fn2

It’s a curious and enlightening passage. It is the source which reveals the duke’s role in his preferment, but it is also a throwaway scrap – perhaps penned in the idle hours of a lazy afternoon – that allows us to peer into Parker’s mind. There is pride and satisfaction at his achievement, which he relives in prose, jotting it down like a little victory. But there’s also something more. Why should Parker choose to record it in the parish register? Why should he, so new to the village, affix his signature and several celebratory lines to the head of a book which by then was more than a century old and intended for an utterly different purpose? None of Parker’s predecessors had been driven to such a thing, and it reveals either a calculated assertion of his presence or an unintentional slip of vanity.

These traces of Parker stem from his first years in Oddingley, which were seemingly his happiest.

11

He forged several friendships, one with Reverend Reginald Pyndar of the neighbouring parish of Hadzor, a justice of the peace, and another with Oddingley’s ubiquitous clerk, John Pardoe. In the mid-1790s Parker met and married Mary, a lady from a humble background, and commenced a happy marriage, which produced a daughter in 1799, also called Mary.

The best account of Parker from this time comes in a memoir written by Benjamin Sanders, a button maker from Bromsgrove who met and befriended him while at Worcester planning his family’s emigration to America. The friendship between Parker and Sanders was brief, lasting just six months, but it was one of significant emotional intensity. Sanders’ recollections must date to the mid-1790s and they show Parker at his best.

At Worcester I became acquainted with a clergyman,

12

in a singular kind of way; we met merely by chance. It is wonderful how, where congeniality of disposition exists, how soon and firmly friendship gets cemented. Such was the case with the gentleman, the Rev. Mr Parker and myself. He had two livings, one at Hoddingley [

sic

] and another at Dorking, he was a great favourite of the late Duke of Norfolk. We became most confidential friends. He would often hope my wife and I would alter our minds and remain in England, and that he would contribute half his fortune if we would do so, but our minds were fixed. We remained six months in Worcester. I went to Bristol and engaged our passage to New York (Alas! the time was now come for my father and me to part, never to see each other more in this world.) This was a severe trial, it seemed to penetrate to the innermost recesses of my heart; but my friend [Parker] was near me to give me consolation in my present affliction; he was a good and most sincere friend. He proposed to walk with us twelve miles, on the road, he informed me by the way that he should soon get married to a lady after his own disposition – a most amiable one I am certain.