Daily Life in Elizabethan England (22 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

Levels of taxation were generally low compared to other parts of Europe.

Taxes were mostly applied to imported goods, in the form of customs duty paid by the importing merchant, although towns might also impose taxes on transactions by traders who did not belong to the town. Tithes were paid to the parish church annually, but there was no equivalent taxation by the government under normal circumstances. In time of need, Parliament

104

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Table 5.3.

Sample Prices of Goods and Services

Meal at an inn

4–6d.

Gentleman’s meal

2s.

in his room at an inn

Bed in an inn

1d.

Lodging a horse

12–18d.

Food for one day

4d.

Loaf of bread

1d.

Butter (1 lb.)

3d.

Cheese (1 lb.)

1½d.

Eggs (3)

1d.

Fresh salmon

13s. 4d.

Beef (1 lb.)

3d.

Cherries (1 lb.)

3d.

Sugar (1 lb.)

20s.

Cloves (1 lb.)

11s.

Pepper (1 lb.)

4s.

Wine (1 qt.)

1s.

Ale (1 qt.)

½d.

Tobacco

3s./ounce

Officer’s canvas

14s. 5d.

Officer’s cassock

27s. 7d.

doublet

Shoes

1s.

White silk hose

25s.

Candles (48)

3s. 3d.

Soap (1 lb.)

4d.

Knives (2)

8d.

Bed

4s.

Spectacles (2 pr.)

6d.

Scissors

6d.

Bible

£2

Broadside ballad

1d.

Small book

6d.–2s.

Theater admission

1, 2, or 3d.

Tooth pulled

2s.

Portraits

62s. to £6

Horse

£1–2

Hiring a horse

12d./day or Hiring a coach

10s./day

2½d./mile

might vote a subsidy, a one-time tax of varying rates, assessed proportionally to property or income among those who had the means to pay—only a minority of households were expected to contribute. The ongoing cost of multifront wars during the 1590s, with repeated subsidies to cover the expense, was a significant factor in England’s economic downturn during that decade.2

THE LIVING ENVIRONMENT

Villages

The overwhelming majority of the population lived in the country,

typically in villages of about 200 to 500 people. The village in areas of

Material Culture

105

open-field settlement consisted of a cluster of homes around one or more unpaved streets. The center of the village was also the site of the parish church, which was likely to be the oldest building in the village, and perhaps a village green. The central area might also have a manor hall and other manorial buildings grouped within a walled enclosure. These buildings might also be old, especially if there was no longer a resident manor lord; if the complex was currently inhabited, the hall was likely to have been rebuilt or at least renovated in recent years to accommodate current fashions in architecture.

There was necessarily a good source of water near the village center, whether a river or a well, and often both. Around the clustered homes were the village fields, pastures, and meadows, and beyond that were waste areas such as woods or marshes. Somewhere in the lands of the manor there would be a blacksmith, and at least one water-powered mill, or perhaps a windmill in the windblown parts of the country adjoining the North Sea.

The village was primarily a phenomenon of champion farmland. In

areas of woodland agriculture, houses were likely to stand alone in the midst of their holdings, or in small clusters that were sometimes called hamlets.

Towns

Town location was heavily influenced by transportation. The most

important towns were located on navigable rivers, usually at the site of one or more bridges, and all towns were hubs in the network of major roads. The larger towns were usually walled, and might also have a castle; walls and castles were among the oldest features in a town, often dating to the Middle Ages or even to Roman times. There were few other public structures in most towns. There might be a stone cross in the square where the market took place, or even a covered market building. If there was a municipal government, there would be some sort of town hall— sometimes no more than a large room above the market. Otherwise, the only public buildings were churches and their associated buildings, which often served secular as well as religious functions: meeting hall, courtroom, school, business place, muster hall, and armory. Specific crafts and trades tended to cluster in certain areas of the town, which facilitated guild administration.

Town streets had names, although houses were not numbered. Even

London was rather small by modern standards, so it was possible to identify individual buildings by the name of their principal occupants or functions. Many buildings were named for an iconic sign that decorated the outside: the Swan, the Red Lion, the Green Dragon. Some city streets were surfaced with cobblestones, but many were unpaved and became difficult to use in wet weather when feet, hooves, and wheels churned them into a

106

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

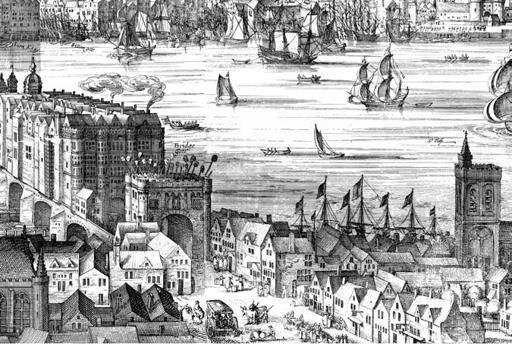

The south end of London Bridge. [

Shakespeare’s England

]

river of mud. A few streets were extremely broad, wide enough to be used as marketplaces or football fields.

Fire was a major hazard in urban environments. In spite of attempts to reduce the danger by passing laws against thatched or wooden roofs, fire remained an ever-present threat in an environment where buildings were crowded, most construction was of wood, and light and heat were provided by fire. There was no official fire department, but churches and

STREET LIFE IN LONDON

In every street, carts and coaches make such a thundering as if the world ran upon wheels; at every corner men, women and children meet in such shoals, that posts are set up of purpose to strengthen the houses, lest with jostling one another they should shoulder them down. Besides, hammers are beating in once place; tubs hooping in another; pots clinking in a third; water tankards running at tilt in a fourth. Here are porters sweating under burdens, their merchant’s men bearing bags of money. Chapmen (as if they were at leapfrog) skip out of one shop into another. Tradesmen (as if they were dancing galliards) are lusty at legs and never stand still. All are as busy as country attorneys at an assizes.

Thomas Dekker,

Seven Deadly Sinnes of London

[1606], ed. H. F. B. Brett-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1922), 37–38.

Material Culture

107

other public places often stocked fire-fighting equipment for residents to use in case of emergency. These included leather buckets for fetching water, and ladders and hooks with which to pull down burning buildings before the fire spread—the origin of the modern hook-and-ladder squad.

THE HOME

“A man’s house is his castle,” wrote the jurist Sir Edward Coke in the early 17th century. The sentiment still resonates today, yet the meaning of one’s house for people in Coke’s day was not the same as it is for us.

Today the house is a place of refuge, the place for private life. Although these trends had roots in the Elizabethan period, the distinction between a person’s private and public life was much less clear-cut than it is today.

For the Elizabethan, the home was not just a private space: it was the focus of all aspects of life. People were born in their homes, they died in their homes, and often they worked in their homes too.

The nature of the home and its contents was changing during Elizabeth’s reign. Overall, to a modern person, the material culture of the period would recall circumstances in the modern developing world. There was a

A PARISH MINISTER REMARKS ON

RISING STANDARDS OF LIVING, 1577

There are old men yet dwelling in the village where I remain which have noted three things to be marvellously altered in England within their sound remembrance. . . . One is the multitude of chimneys lately erected . . . The second is the great (although not general) amendment of lodging; for, said they, our fathers, yea and we ourselves also, have lain full oft upon straw pallets, on rough mats covered only with a sheet, under coverlets made of dagswain or hopharlots (I use their own terms), and a good round log under their heads instead of a bolster or pillow. If it were so that our fathers or the good man of the house had within seven years after his marriage purchased a mattress or flock bed, and thereto a stack of chaff to rest his head upon, he thought himself to be as well lodged as the lord of the town, that peradventure lay seldom in a bed of down or whole feathers, so well were they content, and with such base kind of furniture. . . . Pillows (said they) were thought meet only for women in childbed. As for servants, if they had any sheet above them, it was well, for seldom had they any under their bodies to keep them from the pricking straws that ran oft through the canvas of the pallet and rased their hardened hides. The third thing they tell of is the exchange of vessel, as of treen [wooden] platters into pewter, and wooden spoons into silver or tin.

William Harrison,

The Description of England,

ed. Georges Edelen (Ithaca, NY: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1968), 200–201.

108

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

vast difference between the lifestyles of the upper class and those of ordinary people; most houses were small and simply furnished, and personal property for most people was limited. But standards of living were on the rise: contemporaries remarked on the more comfortable furniture, finer tableware, and better constructed homes that were enjoyed by the middling sort, compared to circumstances a generation earlier.

Then as now, the nature of one’s dwelling varied between the city and the country, as well as between social classes. There were also distinctive building traditions in each area of the country, as well as differences of design between any one house and another. The following pages will describe the technology of house construction, followed by the layout of three major types: the rural home, the gentleman’s manor house, and the town house.

The Home

Most Elizabethan houses were based on jointed frames of oak: instead of nails, which would be too weak, the timbers were carved with tongues (tenons) and slots (mortices) so that the whole frame fit together, with the tenons secured in their mortices by thick wooden pegs. Ideally the frame would rest on a stone foundation, since prolonged contact with moisture in the ground would eventually cause the timbers to rot. However, the cheapest sorts of structures simply had their main posts sunk into the ground.

The basic frame carried the weight of the house, and it had to be filled in to make the walls. The typical means of filling was a technique known as

wattle and daub.

Wattling consisted of upright wooden stakes fixed at the top and bottom into the horizontal timbers of the house, with pliant sticks woven between them. The wattling served as a core for the wall, which was covered with daub—a mixture of clay, sand, and animal manure, with chopped straw or horsehair added for strength. Well-appointed homes might be plastered on the inside and outside, and the ceiling might also be plastered. These plasters were often more robust than the modern equivalent, mixed from lime, sand, and animal hair. In a very wealthy household, the interior walls and ceilings might be wainscoted with wooden panel-ing, often brightly painted or covered with tooled leather. Some interiors were surfaced with patterned woodblock wallpaper. The exterior of the building was usually coated with a limewash to prevent rain from damaging the water-soluble layers underneath. Limewash might also be used to coat interior surfaces, helping to preserve the surfaces, brighten the rooms, and deter insects.

Most English houses in this period were constructed in some version of this technique. In some places, lath and plaster took the place of wattle and daub: strips of wood were nailed to the upright stakes, serving as a base for a plaster covering. Those who had the money might use bricks to fill in the frame; this provided greater security against fire but it was much

Material Culture

109

more costly. In areas where stone was plentiful, particularly the west and north, houses were often built of stone, but in other parts of the country stone was too expensive except for the very rich.

The commonest form of roofing was thatch, a very thick covering made with reeds or straw. A thatch roof was durable and an excellent insula-tor, although it could also be a haven for vermin, and it posed a serious fire risk as well. Alternatives were clay tiles, slate, or shingles. Tiles were expensive, as was slate (except in areas where it was naturally plentiful), while shingles were only readily available in regions with plenty of trees.