Daily Life In Colonial Latin America (28 page)

Read Daily Life In Colonial Latin America Online

Authors: Ann Jefferson

A more exclusive variety of theatrical performance was the

formal play presented in an enclosed space designed for that purpose. Members

of the colonial elite had been accustomed to taking in such entertainment in

the privacy of the vice-regal palace or a similar venue since the early

colonial era. By the late 16th century, playhouses known as

corrales,

privately

owned and usually very basic in their amenities, were offering such

performances to the wider public in Mexico City as well. The survival of these

private playhouses was always precarious, however, as the crown had granted a

formal monopoly on this type of performance to an officially licensed theater

that began operating in the city’s Royal Indian Hospital during the 1560s. A

similar, officially sanctioned theater opened in Lima in 1601, in the Royal

Hospital of San Andrés.

Audience Expectations and Public Morality

Audience expectations of the theater appear to have varied

greatly by social condition, especially in public circumstances where people

from more than one level of society were thrown together. In the late 18th

century, elite patrons of Mexico City’s New Coliseum, opened in 1753 as the

last in a series of buildings constructed to house the performances allowed

under the Royal Indian Hospital’s license, complained frequently about the

boisterous behavior exhibited by audience members from the city’s poor, mostly

casta

majority. The latter, congregated in the cheap seats, talked and ate during

performances, called out to the actors, and loudly applauded a variety of

between-acts dances and other short entertainments that were often criticized

instead by the authorities and the “better” sort of patron as lewd or otherwise

morally suspect. After the play was finished, the actors, poorly paid for the

most part, often accompanied the lower-class audience members to a nearby alley

where the festivities were renewed through the presentation of crowd-pleasing

puppet shows. These gatherings provided a little more income for members of the

performing classes and an even less restrained ambience for audiences

uninterested in the supposedly more refined pleasures of the upper classes.

Like 16th-century missionaries, appalled advocates of

18th-century Enlightenment values sought to transform the theater into a form

of moral education for the common people. The emphasis of that education was

shifted somewhat, however, from a focus on religious doctrine to principles

associated by their advocates with reason and order. To this effect, New Spain’s

Theater Regulations of 1786, implemented by one noted proponent of these

principles, Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez,

strengthened

existing forms of censorship,

sharply restricted the apparel and behavior that actresses in particular could

exhibit on the stage, and prescribed a standardized set of penalties (up to and

including eight days’ imprisonment!) for audience members found guilty of

creating “disorder.” Gálvez also had his perspective on the theater’s purpose

inscribed on the curtain of the New Coliseum, for the benefit of all audience

members. It ran as follows:

Drama is my name

and my duty is to correct

mankind

in the exercise of my profession

friend of virtue, enemy of vice.

As in the crackdown on the social ills associated with

religious festivals and pulquerías, the marginalized segments of society bore

the brunt of theater reforms intended to improve them. Women, for example, had

been gradually increasing their participation in the theatrical world during

the 17th and early 18th centuries, despite church disapproval, to the extent

that several were able to assume posts as directors in New Spain. But the last

of them, María Ordóñez, was eventually locked up for years in a series of

casas

de recogimiento,

institutions in which women were sequestered for various

reasons including “moral lapses.” When Ordóñez finally won release in 1794, it

was only with the warning that the slightest misstep in conduct would result in

her immediate reincarceration.

DEATH, DYING, AND CULTURAL CONFLICT

The contest between colonial authorities, whether religious

or secular, and colonial subjects to define the nature and parameters of daily

cultural practice culminated in the rituals associated with the end of life.

For its part, the church had a key stake in the issue, given its fundamental

concern with determining the manner in which all significant life passages were

observed. As with two other important transitions, birth and marriage, a Roman Catholic

priest was to administer a sacrament—in this case extreme unction, also known

as the last rites—to all individuals experiencing the transition. The ceremony

involved anointment of the dying person’s sensory organs with holy oil,

accompanied by petitions offered on his or her behalf, and was intended as a

last cleansing of sins in preparation for final judgment in the afterlife. Once

death had taken place, a funeral mass and burial of the corpse, again in

accordance with the church’s precisely scripted rituals, was to follow shortly.

This 18th-century Catholic

death-bed manuscript from Mexico reminds the churchgoer that a sinner cannot

enter heaven. Part of the inscription tells us that the dying man knows he has

sinned and does not know if he is pardoned. “I want to begin to do what I wish

I had done,” he says. But it may be too late; notice the devil waiting under

the bed for his prey.

As we have already seen, however, unorthodox practices

frequently escaped the efforts of the authorities to control them, sparking

both repression of and accommodation to the popular will on the part of ruling

sectors interested in maintaining social control as best as they could.

Nowhere, perhaps, was this tension more evident than in the beliefs and

practices associated with death and dying. All societies have developed

powerful ideas about proper disposal of the dead, and most have also assumed

the existence of an afterlife and the need to mediate the relationship between

the living and the dead in one way or another. The native societies encountered

by the Iberians in the New World were no exception, nor were the African ones

from which involuntary migrants were forcibly transported to the Americas. The

Spanish and Portuguese themselves, especially the majority of commoners, held

on to and acted on many notions regarding the dead and the spirit world that

were distinctly at odds with Christian doctrine. Sometimes the church was able

to suppress such notions, but it was forced to tolerate others more or less openly,

seeing them as hopelessly ineradicable remnants of what it characterized as

pagan superstition.

Popular Celebrations of the Dead

The present-day Mexican celebration of the Day of the Dead

provides one example of the persistence in Latin America of rituals surrounding

death and dying that do not conform to the beliefs the church first began

imposing five centuries ago. A crucial aspect of the celebration involves treks

to the graves of relatives in local cemeteries by families laden with food and

drink to be shared with the deceased. The ritual takes place as the Christian

calendar is marking All Saints’ Day and then All Souls’ Day on November 1–2, a

clear sign of the church’s influence. Nevertheless, many of its primary

elements reflect non-Christian understandings of communion with the spirit

world.

During the colonial era, Mexican priests regularly took

note of the beliefs and practices that continue to inform the Day of the Dead

festival, criticizing them but also interpreting them in a manner that made

them appear compatible with Christianity, a clear sign of resignation in the

face of traditions too strong to be eliminated. The long-standing appeal of All

Souls’ Day to Mexico’s native peoples is indicated in a 1766 guide for priests

in the diocese of Puebla. The guide described the preparations made by local

Indians as the holiday approached: sweeping the streets and patios of their

houses and setting out fruit and bread for the return of deceased relatives.

Other unorthodox rituals reported in the guide included the practice of leaving

the clothing of deceased individuals at the place of death for a week and

burying corpses with sandals. Indeed, the list of items buried with a dead

relative might include provisions, money, and even farm implements. While the

handbook expressed disapproval of such acts, the priests who read it were

encouraged not to view them as fundamentally opposed to the church’s teachings,

in other words not to concern themselves too greatly with trying to eliminate

them.

Rituals of a similar nature were reportedly practiced by

people of African origins in Brazil. A bishop visiting Minas Gerais in 1726

described members of the local enslaved population “singing and playing

instruments for their dead” and “getting together in stores where they bought

various food and drinks, which after they ate they threw into the grave.” Once

again, practices that proved impossible to root out were accommodated by the

church, evident in the fact that some Catholic brotherhoods of the Rosary in

Brazil continue to incorporate drumming and songs associated with the rituals

of enslaved Africans into burial rites for deceased members. There were,

nevertheless, distinct limits to the church’s strategy of tolerance, as made

clear in the earlier discussion of the campaign to eradicate idolatry in the

Andes. Church authorities viewed late-colonial reports that native peoples in a

few central Mexican villages were throwing their dead down ravines to be

devoured by wild animals as nothing other than proof of their incorrigibly evil

natures, not to mention the devil’s ongoing efforts to rob the church of the

souls its approved rituals were meant to save.

Royal officials, meanwhile, were sometimes alarmed even by

the sort of attention paid by the public to properly Catholic observances of

death and burial. The Spanish crown issued decrees against extravagance in the

purchase of mourning clothes, considered by many Spaniards to be an essential

component of their wardrobe and an important gauge of status. The same crown

was disturbed by reports of excessive popular enthusiasm for the processions

and other rituals that attended a corpse as it was being conducted to its final

resting place; therefore, the crown attempted to ban public displays of

mourning unless the social status of the deceased individual was sufficiently

grand as to warrant it. As with many other aspects of popular culture, the

attitudes of the authorities toward the ritualized behaviors surrounding

processes of death and dying seem to have been shaped primarily by the

implications of those behaviors for the maintenance of the prevailing colonial

order.

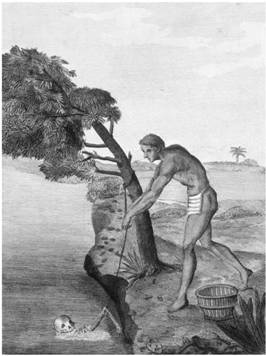

An

1811 engraving of a funeral rite attributed to one of the Tupi-Guaraní peoples

living along the Orinoco River in the Amazon basin. Some indigenous people

practiced rites in which the flesh was removed from the skeleton and the bones

were used for ritual ornaments.

CONCLUSION

In colonial Latin America, both religious and royal

authorities believed they had not only the right but the duty to legislate

morality and restrain what they viewed as the excesses of a flourishing popular

culture. Somewhat ironically, the church at the same time sponsored some of the

most important vehicles for those alleged excesses, such as the cofradía. This

seeming contradiction was arguably the logical consequence of the church’s

efforts to control all forms of cultural expression. Pushed to respond to the

spiritual or other enthusiasms of an exploited and potentially restive

majority, it sought both to encourage those enthusiasms and to contain them

within acceptable boundaries.

At the same time, a major obstacle to the successful

transfer of a narrowly Iberian Catholic cultural model to the Americas was the

diversity of the populations over which the Spanish and Portuguese ruled. It is

not surprising that colonial authorities were unable to impose cultural

uniformity with anything approaching complete success on societies that forced

together peoples of widely varying indigenous, European, and African

backgrounds. The yawning social and economic gap between a tiny elite of

wealthy

peninsulares

and creoles, on the one hand, and a poor, largely

non-European majority, on the other, also contributed to the persistence of

distinctive cultural practices among different sectors of the population. Each

of those sectors experienced the profound impact of Iberian Catholic rule in

its own way. The next chapter shifts the angle from which to view the

significance of that form of rule for colonial daily life, bringing into focus Spanish

and Portuguese administrative strategies in the Americas and popular responses

to those strategies, both peaceful and violent.

7 - GOVERNMENT, POLITICAL LIFE,

AND REBELLION

INTRODUCTION

The

imposition of forced labor systems, as well as alien religious and cultural

norms, on native peoples and unwilling African migrants in the Americas was

accomplished under the umbrella of a royal administrative structure created to

manifest the will of the king in the actions of even the most petty local official.

Laws rapidly proliferated; when the Spanish crown collected the extensive and

sometimes contradictory legislation it had emitted over nearly two centuries in

a single publication in 1681, the resulting

Recopilación de leyes de los

reynos de las Indias

ran to several thousand regulations. But the

relationship between law and daily life was not one-to-one in either Spanish

America or Brazil. Royal officials often protected their own vested interests

by expressing what they claimed was the king’s will in ways that were markedly

at odds with the evident intent of the royal decree. Such legal flexibility

helps to explain the fact that colonial rule persisted for three long centuries

in Latin America. Indeed, overt resistance rarely threatened the colonial system

during most of this period, not because conflict was absent but because it was

usually contained by some combination of official willingness to accommodate

popular grievances and the tendency of marginalized people to “work the system”

to their “minimum disadvantage” more or less peacefully, in the formulation of one

eminent historian. Nonetheless, the threat of violence on the part of both

rulers and ruled was never entirely absent. This chapter examines colonial rule

and popular responses to it, up to and including armed revolt and repression.