Daily Life During The Reformation (25 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

A lower class widow had little opportunity of making a

decent living unless she had been left a shop or business by her deceased

husband. A woman in the upper middle class who had property needed to be

protected by her family against fortune hunters. Widows needed to show piety

and modesty in England if they were to avoid slanderous gossip.

FUNERALS

No church bells were rung for the dying or the dead in

Saxony. As with weddings, people were invited to funerals by a horseman and a

lackey going from door to door. The bier was set down in the street the day

before the burial, and notice of the dead was given by the preacher from the

pulpit. They were usually buried in coffins with windows over the face to be

opened and shut as the mourner wished. In most places people were not buried in

a church yard but in some walled ground outside the city that contained a

cloister around the wall and a little chapel. The cemetery was called

Gottsacker or God’s acre. The wealthy reserved places under the cloister for

themselves and their family. Others were interred in a field. The monuments had

painted or engraved crosses. The preacher would make a short sermon, and the

Lutheran witnesses would remain silent in some towns or sang a psalm in others.

If a hospital patient in England died, burial normally took

place the next day. A procession of friends and relatives followed a few

musicians who accompanied the body to the graveyard. For a woman, a wreath of

flowers and herbs was carried in front of the coffin by a close friend, a glove

placed at the center of it symbolizing virginity. Mourners often laid rosemary,

bay leaves, or other evergreens on the coffin to symbolize the soul’s

immortality. Both Protestants and Catholics wanted a fine sermon preached for

the deceased after which elaborate refreshments were served back at the house.

If the bereaved were wealthy, this was sometimes followed by days of feasting

and drinking. The poor also had funeral feasts, much of which was contributed

by the guests. Sometimes mourners were engaged to walk in the procession, their

food and clothing for the occasion being paid for by the family.

Among the chief mourners, the women covered their faces

with white linen and the men with black so they had to be led by a servant to

the site. Funerals were frequent, and ministers were paid for their prayers.

At the death of a prince, more ostentatious practices took

place. Moryson witnessed the funeral of the Elector of Saxony as well as the

ceremonies in Dresden where he died. There the body was laid out with the face

exposed for two days for all to see. The body had a velvet cap decorated with

an expensive jewel. To be buried with him was a gold chain around the neck, a

tablet of the fellowship between the Protestant princes of the union, three

rings on his fingers: a diamond, a ruby, and a turquoise; two bracelets of gold

on his arms; and a gilded hammer in his right hand. His coat of armor, his

rapier, spurs, and diverse banners lay nearby on display. After two days, the

body was enclosed in copper and sent from Dresden to Freiburg (a day’s

journey), with bells ringing in all the churches along the way. He was

eventually buried with great pomp in the main church of the city. The Latin

inscription (rendered into modern English) read:

Has here been deposed what so ever was mortal, his soul

immortal in joyous eternal happiness with God. You, mindful of human frailty,

prepare thyself to follow him in the same steps of true piety, and faith in

God, in which he has gone before you.

Along the route, memorial coins minted for the purpose,

were scattered among the crowds.

INHERITANCE

In some places as in England and France, primogeniture was

strictly adhered to, whereby the first son inherited everything. In Germany,

however, inheritance was more equally divided between all the children,

although the first son still received the major share of not only money and

estate but also of educational opportunities. Under the rule of primogeniture

in England, the older boy was expected to care for his parents in their old age.

If he had brothers, he was responsible for their welfare and to see they

received training to become courtiers, diplomats, lawyers, or serve in the

military, so they could follow distinguished careers. In fact, the younger

siblings often fell subject to neglect and abuse. Too, if there were many

brothers and sisters, the burden on the oldest son could become intolerable.

11 - LEISURE AND THE ARTS

GAMES AND SPORTS

Throughout

Europe, boys wrestled and took part in mock fights: they ran, leapt over obstacles,

competed at archery, threw the javelin or stones, and engaged in tug of war, or

whatever tested their strength and prowess. Games for girls and boys included

blind man’s bluff, hide and seek, riding hobby horses, spinning tops, hitting

shuttlecocks back and forth, and leapfrog. In cold weather there were snowball

fights, sledding, and especially in Holland, young people skated by tying bones

to the soles of their shoes.

Wooden hoops or wheels were bowled along with sticks.

Tennis and croquet originated in France at this time. Punch and Judy shows

began in Italy in the sixteenth century and made their way across Europe to

England as marionettes or puppets. Some children had a jack-in-the-box, the

Jack often being an admiral on a stick or a Punch with a horrible face.

Peasant children, such as those who lived in the Swiss and

German mountain areas, played at riding wooden horses; tossing rocks, quoits,

and rings; blowing the horns of shepherds; and jumping rope. They also had toys

that included puppet soldiers, dolls, balls, stilts, marbles, kites, and tops.

Along with the adults, they played skittles and chess.

In sixteenth-century Scotland and elsewhere, children often

made their own toys, such as paper windmills and little boats. By the time of

James VI, dolls, rattles, and whistles were being imported.

Curling was well established by this time in Scotland and

the Netherlands. The Scottish played the game with large, smooth stones called

granites, held and sent on their way by means of a handle attached to the top.

The earliest known stone that was used for curling dates from 1511. The first

depictions of curling in the Netherlands are found in the mid-sixteenth century

paintings by Brueghel. It is thought that early Dutch and Flemish players used

lumps of frozen earth or ice with a wooden handle frozen into them.

The first book on the game of checkers, was written in 1547

by Antonio Torquemada. Although the game was probably well known from ancient

times, it was more sophisticated than earlier board games.

In Scotland the rich took part in archery, hunting,

hawking, and golf. In 1576, the imprisoned Mary, Queen of Scots, lamented that

her billiard table had been taken away. Mary may have learned to play the

popular game in France, whence it was imported into England. It was played with

only two balls that were hit with the end of a tool that resembled a hockey

stick. The table, covered in a green cloth, had cushioned sides that were

packed with pieces of felt. Some tables had pockets, others had obstacles such

as hoops, pegs, or miniature military fortifications on the cloth.

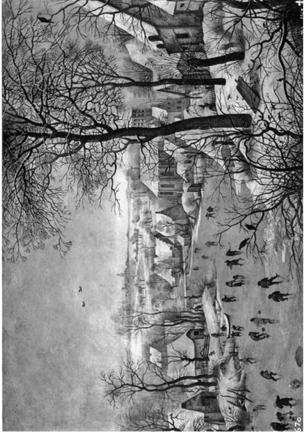

Children’s Games, Pieter

Brueghel the Elder, 1560. This painting depicts some 200 children engaged in

various activities including many individual games.

Ice skating on a lake in winter,

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, 1568.

FRANCE

Upper Class

The royal court and the grand nobility of France spent much

time and money on entertainment. The lavish balls at the royal palaces, such as

the Louvre in Paris and nearby Fontainebleau, often in costume, accompanied by

sumptuous dinners, spared no expense. These Bacchanalian affairs involved

drinking, eating, music, dancing, gambling, plays, and flirtations.

Tournaments were also popular but had become more pageantry

than battle. Jousting was still practiced, but resulted in few fatalities

although King Henri II, a participant in a joust, was fatally wounded on June

30, 1559. By the end of the century, noblemen were tilting their lances at

wooden targets rather than at an armed opponent.

Other aristocratic pastimes entailed dice, cards, chess,

and tennis in which the ball was hit with the palm of the hand (

Jeu de paume

). There were also bowls,

fencing, hunting, and a brutal type of entertainment entailing fights to the

death between animals. The royal spectators enjoyed watching lions, tigers, and

bears tear each other to pieces or mastiffs pitted against bulls in mortal

combat.

Lower Classes

The common people had their own forms of entertainment.

Folk drama, jugglers, and ballad singers flourished in the festivals and fairs

of country and city as they had since early medieval times. There were

celebrations in honor of the parish, the guilds, the lord of the manor, his

wife, the worker, for births, marriages, Communion, a visit of the king or

queen to the city and the numerous Church holidays such as Christmas, Easter,

and saints’ days.

Parisians especially loved bonfire displays that lit up the

public buildings or city hall to commemorate some past event when everyone came

into the streets to dance, sing and drink. On June 23, eve of the day of

Saint-Jean, a tall tree was placed in the Place de Greve surrounded by a large

pyre on which hung sacks full of cats. The official executioner had the

privilege of erecting a grandstand around the pyre and renting the seats. At

seven o’clock trumpets sounded, artillery fire resounded throughout the town,

and fireworks were set off. Municipal magistrates and the provost arrived,

their heads crowned with roses. Having walked three times around the pyre with

a lighted torch, and if the king was present, the provost on bended knee,

handed him the torch to light the pyre. The fire soon consumed the tree while

the audience with great jubilation shouted and clapped drowning out the

horrific and pitiful cries of the animals burned alive. Many festivities called

for the torture and death of animals not unlike those humans accused of certain

crimes. Similar fires took place at the same time in different quarters in the

squares in front of major churches and the celebrations, accompanied by bread

and much wine, continued until dawn.

Bookshops and Stalls

There were nearly 400 book outlets in Paris at the end of

the sixteenth century. For those who could read, diverse subjects were

available such as astrology, astronomy, travel stories, works of famous Greek

and Latin authors, natural events including floods, comets, supposedly

miraculous happenings, crimes, politics, and battles. Michel de Montaigne was

one of France’s most influential writers, and his works sold well, as did the

poetry of Ronsard, duBellay, and others. There was a good deal of forgery,

copying of works, and black market Protestant material. A number of books and

pamphlets were secretly imported from the presses in the Netherlands, but the

city council kept a sharp eye out for subversive ideas.