Daily Life During the French Revolution (27 page)

Read Daily Life During the French Revolution Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Went

to the Hospital de Salpetriere, a little way out of Paris, a sort of workhouse

for girls and women, of which there are in the house 7500. I saw 400 at work in

one room: 500 in another. They embroider, make lace and shirts, and weave

coarse linen, also cloth; all which is sold for the benefit of the hospital. .

. . It is also an Asylum to such poor families whose head is dead, or has

deserted them; in short, it is the asylum of the miserable, tho’ each is

obliged to work to support the whole.

Bicêtr

e, an even larger hospital, was farther

from the center of Paris and had fewer curious visitors. According to Dr. John

Andrews, it was a place for “defrauders, cheats, pickpockets . . . convicts for

petty larceny . . . vagrants, idlers, mendicants.” He went on to speak of the

mentally ill and the unemployed. Discipline was severe. Andrews considered

Bicêtre

a humane and useful institution, but opinions differed. In the autumn of

1788, Sir Samuel Romilly, a lawyer and reformer, traveled to Paris and visited

the hospital in the company of others, including the antiroyalist Mirabeau.

Both were horrified at what they saw.

Romilly followed Mirabeau’s suggestion that he write down

what he had seen, and Mirabeau later translated his notes into French and had

them published. The publication was suppressed by the police, but Romilly

published the English text in London. The tenor of the essay was expressed in

the first paragraph:

I

knew, indeed, as every one does, that it [

Bicêtre

] consisted of an

hospital and a prison, but I did not know that, at Bicêtre an hospital means a

place calculated to generate disease and a prison, a nursery of crime.

There were boys under the age of 12 incarcerated there, and

men who were often kept for years in underground dungeons. In the common room

were boys and men who had simply argued with or insulted the police on the

streets of Paris. Every vice was practiced; the author felt obliged to describe

these in Latin.

DENTISTS

Joseph Daniel, who called himself a surgeon dentist, fitted

crowns of a new design that would function like natural teeth. He claimed that

they would always keep their color. One of his advertisements read as follows:

DENTALSURGEON

M.

Daniel, dental surgeon, Fossés-St. Germain l’Auxerrois Street, no. 15, has

acquired, by long experience, much dexterity in removing the most difficult

teeth and roots when they cannot be preserved. He cleans, whitens and dries

them and destroys the nerve, fills them successfully, takes out **geminates,

puts back the good ones and inserts artificial teeth, **on spring-loaded posts

of a new invention, stable and unbreakable. He has also discovered a metallic

thread for teeth and false teeth much cheaper than gold. He blends a toothpaste

for tooth and gum care; 3 livres and 6 livres per jar.

CP—13 April 1792

In addition to cleaning and extracting teeth, dental

practitioners sold a variety of painkillers. They were also interested in the

repair of decayed teeth and the replacement of lost ones. By the 1790s, complex

restorative and prosthetic techniques and specialist dental practice was well

established.

To have a tooth extracted, the patient was normally seated

in a low chair or on the ground, while the dentist stood over him, tongs in

hand. As the patient held on to the dentist’s legs for support, the toothpuller

could certainly tell how much pain he was causing by the intensity of the

grasp, but conducting the procedure in this manner benefited the dentist, for

it allowed him to get a good grip on the tooth and jerk it out.

One of the most flamboyant mid-eighteenth-century tooth

extractors was a huge man called Le Grand Thomas, who could usually be found on

the Pont Neuf in Paris. Accompanied by his magnificent horse, adorned with an

immense number of teeth strung like pearls around its neck, assistants would

examine the teeth of any willing passerby to see what might need to come out.

Thomas stood by in his hat of solid silver, which balanced a globe on top and a

cockerel above that. His scarlet coat was ornamented with teeth, jawbones, and

shiny stones, a dazzling breastplate represented the sun, and his heavy saber

was six feet long. A drummer, a trumpet player, and a standard-bearer made up

the balance of his retinue. Grand Thomas did not live to see the revolution,

but there were thousands of such rogues around the country who seem to have had

little trouble finding patients. Most people of the time neglected their teeth

until something drastic had to be done. Only the rich could afford a qualified

dentist.

By 1768, to become a dentist, a practitioner was obliged to

present himself for examination by the community of surgeons of the town in

which he wished to practice and to have previously served either two complete

and consecutive years’ apprenticeship with a master surgeon or an expert who

was established in or around Paris or three years’ apprenticeship with several

master surgeons or experts in other towns. Dentists in Paris and other large

cities were trained at the

Collège Royal de Chirurgie

(Royal College of

Surgery), which opened in 1776. They had to pass examinations in both dental

theory and practice and, by the second half of the century, were obliged to

take two separate examinations during the same week—the first one theoretical,

the second practical.

Laws to suppress those who practiced without a license were

poorly enforced up to and during the revolution. Charlatans would set up their

signs, a stage, and other paraphernalia in the square on market day or operate

from an inn or from private premises and advocate a variety of techniques to

remedy toothache, gum disease, and other ailments of the mouth. To ease the

pain of a teething child, magnetized bars were used, as were various

concoctions of herbs and roots. Rattles made of ivory or coral were often hung

around the child’s neck to be chewed on, thus helping to reduce the pain of the

inflamed gums. If necessary, the gum over the emerging tooth was lanced. Sometimes

a blistering ointment was rubbed into the area to make saliva flow.

Other curative measures for toothache included bleeding or

placing leeches behind the ears; the most frequently used remedy was a special

elixir made up of various ingredients to cure decayed and painful teeth.

Gondrain’s elixir was advertised as “dissipating toothache in a trice.” Other

potions eliminated swelling of the gums, nourishing and firming them at the

same time.

One method of stopping toothache was by destroying the

dental nerve by using a file, cauterization, vinegar, essences, and elixirs.

All were mentioned in a booklet put out in 1788. Transplants were also

attempted, but human teeth were scarce and expensive, and most failed to take

root. Taken from a living donor or a corpse, the teeth also had the potential

to transmit disease. Artificial teeth, made from ivory or bone, were also

unsatisfactory because they absorbed odors and soon became discolored. With the

discovery of porcelain for replacement teeth, prosthetic dentistry took a large

step forward at the beginning of the revolution.

Not a great deal is known about the fees charged by

dentists, but there is a document from 1785 that lists a fee of four livres

four sols for an extraction and a filling. Costs for elixirs were usually 5 and

10 livres a bottle, and toothpaste cost 3 to 6 livres. For a small brush

mounted in ivory, the cost was 3 livres. By the end of the eighteenth century,

a number of dentists practiced from a fixed location, especially in large

cities; when they worked in other towns, they rented premises for a few days.

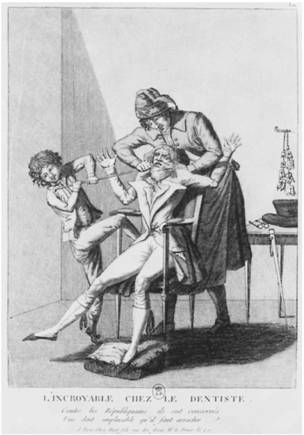

The itinerant dentist, his patient, and interested

onlookers.

The extraction of teeth was very painful!

9 - RELIGION

With

some 170,000 secular and regular priests, the church in France represented the

first order of society, comprising about 26,000 monks and friars, 56,000 nuns,

60,000 curates, 15,000 canons, and 13,000 clerics with no permanent office or

regular duties.

Besides caring for the soul, the church held the monopoly

on primary and secondary education, as well as being a major source of charity.

It maintained registers of births, marriages, and deaths and ran the hospital

system, such as it was, under the old regime.

In rural areas, not only was the village church the center

for the spiritual care of the locals but also it served as the hub of

administrative affairs. The church put order into every aspect of country life:

the tolling of the church bells ordained the rhythm of the daily cycle,

resounding throughout the village when it was time to rise, at noon when it was

the hour for a break, and at vespers, in the evening, when it was appropriate

to pause and say a prayer. The sound of the bell was also the alarm alerting

the populace of a fire or warning of mischief in the village.

The kingdom was divided into 18 archiepiscopal provinces

and 136 dioceses. Many bishops held jurisdiction in more than one: the noble

bishop of Dol, in Brittany, for example, had 33 posts.

LIFE OF A NOBLE CLERIC

A rural abbot, Emmanuel Barbotin, financially well off as a

tithe holder and director of an agricultural business in the north of the

country, was elected representative from Hainaut to the Estates-General. He

wrote letters back to his parish about his day-to-day thoughts and experiences.

In one letter, penned while he was in Paris, he wrote to a fellow priest who

was looking after his farm at Prouvy in the north, with a number of

instructions about selling the oats, wheat, flax, and bundles of faggots in

good time; he informed his caretaker when to plant colza, when to bleach linen,

to whitewash the barns, the bake house, and the pigeon-cote. The abbot also

wondered if there was enough butter for the month of October and asked about

the amount and the quality of the harvest, insisting that the different grains

be sorted as cleanly as possible. Not least important was the condition of the

wine cellar. For this, his instructions were as follows:

If

the red wine is ready to be tapped, it must not be allowed to stand and spoil.

If you haven’t already changed the cask, the wine must be clarified. In order

to do this, you must first broach the cask and put in the cock, draw out the

bung, and, if the cask is full, draw off at least one bottle, beat the whites

of six eggs with a pint of wine, pour it all back into the cask, stir it in

with a stick for five to ten minutes, bung it up well again, let it stand seven

or eight days and then tap.

The abbot also made inquiries about his flock and asked

Father Baratte to try to find the time to teach the children of the village the

catechism:

It

is in childhood that the eternal truths of our religion are engraved most

readily on the spirit, when they can act freely upon hearts devoid of lustful

passions; and we are living in a time when religion needs to be upheld by our

preaching and even more by our practice.

From these instructions it is evident that the abbot lived

a comfortable life on his farm, as did all churchmen of rank in their abbeys,

palaces, and manor houses. Half of the revenues of the large abbeys went into

the pockets of the abbots, whose only qualifications for their positions were

noble birth and the amount of influence they exercised at the royal court.