Custer at the Alamo (45 page)

Read Custer at the Alamo Online

Authors: Gregory Urbach

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Alternate History, #Alternative History

Chapter Thirteen

I woke up from a strange dream. I was standing on a weed-covered hillside above the Little Big Horn, but there were no hordes of hostile Indians. A small village lay in the valley below, mostly hunting lodges, and all was peaceful. Women were curing buffalo hides, children were playing in the cold rushing river, and dogs guarded a herd of horses grazing in the tall green grasses. A red, white and green flag flew from one of the teepees.

My hunting rifle lay on a blanket at my feet. Near a picnic basket. The day was warm, cloudless. Late spring. I was not wearing an army uniform, but a checkered cotton shirt and buckskin breeches. And moccasins. Had I become an Indian?

I plucked at a stringy curl, finding a strand of thin gray hair. Not helpful. Then I remembered my watch, finding it where it should always be, in my breast pocket. The watch I found was not my father-in-law’s, but something more modern, and engraved,

to Autie, with love, from I

. Glancing at the silver facing, I saw a reflection. Distorted, but clear enough to see an old white man wearing spectacles. I took the spectacles off, discovering myself nearsighted, and studied my wrinkled hands.

I was not an Indian. Someone waved from the river, a slender man with long black hair. It looked like Slow, only decades older. Others were coming from the village, gesturing. They wanted me to come down the hill and join them. Smoke was rising from the campfires. I smelled trout. Was I late for supper? I began to stand, but suddenly my knees grew weak. There was pain in my left arm. A shortness of breath. I fell back into the grass, one hand on my heart, the other on my rifle. A beautiful blue sky stretched from horizon to horizon.

* * *

It was morning, dark and cold. I had slept fully clothed except for my boots, which I pulled on with a grunt. I strapped on the Spanish steel saber, then my leather holster with the two Bulldogs. Fifty rounds of ammunition were tucked in my pockets for quick retrieval. I picked up Tom’s Winchester and checked to be sure there was a shell in the chamber. Then I tied the red silk scarf around my neck, careful not to aggravate the deeply bruised wound, and tugged on my gray wide-brimmed campaign hat. If this was to be George Armstrong Custer’s last fight, I’d go out the way I’d lived.

“Good morning, General,” Corporal French said, waiting outside my door.

“Get some sleep?” I asked.

“A little. Hard to get too much,” he explained.

“We’ll sleep good tonight, one way or the other,” I said with a grin.

“Yes, sir,” French said, almost returning the smile.

John appeared. It looked like he hadn’t slept at all. He still carried the flintlock pistol in his belt, but I considered him a noncombatant.

“Doctor Pollard and Mrs. Dickenson will need help in the church. I’d like you to stay there until the fighting’s done,” I said.

“Rather help you, sir,” John protested.

“Not recruiting Buffalo soldiers today,” I said.

“Not recruitin’ who, sir?”

“An all-negro cavalry regiment. The 10th. Maybe someday we’ll make our own 10th regiment, but not now. I need you helping Mrs. Dickenson.”

John reluctantly obeyed, walking slowly toward the decrepit old church while French and I went around the compound, quietly waking the garrison while reminding everyone to stay silent. I found Crockett first and roused his Tennessee boys, most of whom were not even from Tennessee. So much for the myth.

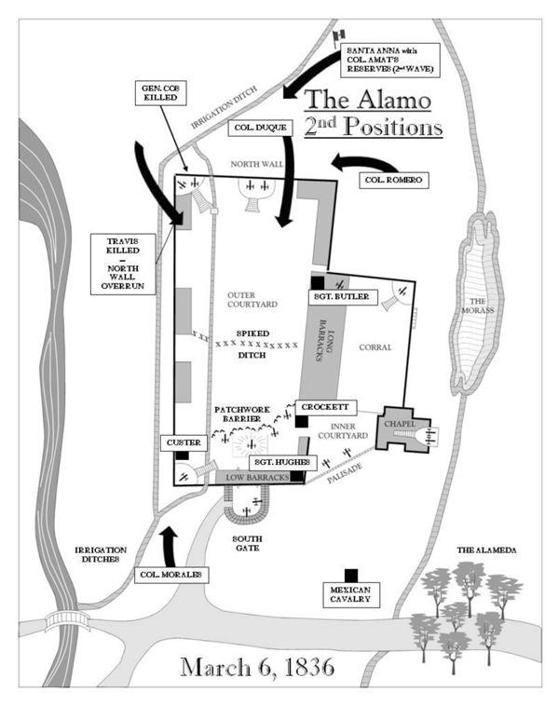

Hughes and Butler had already stirred, putting our men in position. Ten would go with Butler to the roof of the long barracks, eight more on the roof of the low barracks, and the rest would support either me or Crockett inside the south wall. Our internal defense line had been established from the platform holding the 18-pounder at the southwest corner to Crockett’s position before the church. Spotted Eagle and Slow appeared out the darkness. The teenager was ready for a good fight, holding a Colt pistol. A steel hatchet was tucked in his belt. He’d painted his face with red and black streaks. He was also wearing a blue cavalry blouse, the one that had belonged to the late Private Milton of F Company.

Slow seemed a bit withdrawn, his eyes red and arms wrapped in thick fur. He did not look at me with his usual curiosity.

“Light the candles, my friend,” I ordered, handing a torch to Spotted Eagle.

Some people say Indians can see in the dark. I don’t believe it. Growing up in Monroe, nearly everyone was white, but the more I’d seen of different types of people, the more it seemed they were all essentially the same. Except for the defects of their character. Nevertheless, Spotted Eagle was half my age and likely to see better in the dark than I, so he had been given a special mission.

Two paths led from the north wall to our defensive line near the low barracks. Ditches and stake barriers had been placed across the compound to slow an enemy charge, but the obstacles would also hamper the retreat of Travis and his men. To make the withdrawal safer, small oil pots had been placed to mark the planks over the ditches. Once the retreat was complete, the planks would be pulled back and the pots kicked over. At least, that was the plan. Amid the smoke and chaos of battle, who could say what would happen?

Spotted Eagle took the torch and began lighting the pots. I followed, finding Travis in a gutted bungalow on the west wall close to his post. He was already awake but not yet armed.

“What time is it?” he asked.

“A little before four,” I said, checking my watch.

Travis’s slave was sleeping on a pallet in the corner. As slavery goes, Joe’s could be worse. He dressed warmly, ate what Travis ate, and slept where Travis slept. But he was not free to go his own way. There was a time in my life when I wouldn’t have cared. My father had told me that slavery was the South’s problem, but I’d come to believe my father had been wrong about that.

“Morning, Joe. Mrs. Dickenson will be making breakfast in a few minutes,” I said.

Joe looked to Travis, who agreed with a nod. I could tell Travis would prefer to have Joe at his beck and call, but he was not in command. Joe’s ownership was one of the many issues to be decided after the battle. If we were fortunate enough to live so long.

“Thank you, sir. Can I fetch you some, Mr. William?” Joe asked.

“Wish we still had some coffee left,” Travis said, sending Joe away with a wave of his hand. He was still sleepy, the Alabama drawl a bit more pronounced.

“Remember to spike the guns,” I said.

“We won’t need to. They’ll never get over the wall,” Travis replied.

“I need your word.”

“We have spikes and mallets next to each gun. If I can’t hold, we’ll ram the touchholes before withdrawing.”

“That’s good enough for me,” I said, offering to shake hands.

Travis appeared surprised, then accepted the gesture. He seemed the type of a man who would make a good friend or a determined foe.

We walked up the dirt ramp to the bastion on the northwest corner. The gun crew was yet to arrive, but the powder was safely stored under a heavy tarp, protected from the damp weather.

With dawn still two hours away, there was no glimmer of light from the east. If the moon was still up, it was hidden behind the clouds. The platform held two 6-pounders. Solid shot and canister loads were piled along the ledges. Fifteen yards to our right, another platform held two more 6-pounders. Between us, the wall was battered so badly that only a few adobe bricks and bent timbers were holding it together. Jameson had wanted to shore the wall up but I told him not to bother. We were joined a few minutes later.

“Morning, boys,” I whispered, recognizing Bonham and a few others in the dim light. I pointed back across the compound where a dozen small trail markers were burning. “Remember, when you hear the bugle, come running.”

“Won’t need your bugle, sir, but thank you all the same,” Bonham said, wrapped in a heavy fur coat and drinking some sort of warm porridge from a clay mug.

There was no point in arguing.

“Give ‘em hell, boys,” I said, going back down into the compound.

Hughes and Spotted Eagle were waiting for me, and the blond-haired youngster, Jimmy Allen, who I was using as a messenger.

“Everyone at their posts, sir. Some of the powder got a little damp,” Hughes reported.

“Low grain, it will still fire,” I said, hopefully. “Jimmy, tell Crockett to watch out. They might be on us anytime now. Spotted Eagle, make sure Slow stays with Mrs. Dickenson. He worries me. Bobby, check on the 18-pounder. It’s the key to our position.”

They dashed off, no questions and no debate. There was no more time for that. I followed the trail of firepots, not wanting to start the battle in a ditch impaled on a wooden stake. The long barracks lay on my left, a strong position if properly supported. The west wall was to the right, so weak it amazed me that anyone thought it could be held. The wall was barely nine feet high, had no parapets and no bastions. Only a day before, there had been two large holes cut in the adobe for cannon ports that I immediately ordered sealed up. Amateur engineers. Untrained militia. Undisciplined frontiersmen. And lawyers for officers. My God, what had I gotten into?

No, it wasn’t the men. They were better than could be expected, under the circumstances. It was the waiting. My whole career had been spent as a cavalry officer. Sure, there was endless paperwork, tedious ceremonies, and the dreary boredom of life on a frontier post, but when it came time to fight, I was accustomed to probing the enemy, looking for an opening, and launching an attack. Through hard experience, I had learned that taking the offense was the surest path to victory. More often than not, the only path.

Now I was forced to wait behind these walls, on the defense, at the mercy of the enemy’s next move. Just like Major Anderson at Fort Sumter. And John Pemberton, who lost his entire command at Vicksburg. In fact, I could not think of a single instance in recent history where the besieged had emerged victorious. Why hadn’t I thought of that sooner?

I walked quickly about the compound inspecting the preparations, knowing it was too late for any significant changes. Crockett caught up to me near the south gate.

“Calm down, George. You’re gonna make the men nervous,” he said.

“Why don’t they attack?” I said, looking at my watch. “It’s almost five-thirty. What are they waiting for?”

“Maybe Santa Anna changed his mind?”

“That would be rich, wouldn’t it? The goddamned son of a bitch.”

“Now, now, remember what you always say about swearing,” Crockett chastised. And he was right.

Then a shot was fired from the south side.

“To your post, sir. And good luck,” I said.

Crockett needed no extra encouragement, rushing to his position at the palisade.

Another shot, then quiet. It wasn’t a battle yet. I limped in the opposite direction, climbing the ramp to the southwest gun mount, one hand braced on the wall, the other on the 18-pounder. There was definitely movement out in the dark. A rustling of bushes. Shuffling.

“Jameson. Jameson?” I called down into the lunette.

“Yes, general?” he answered.

“Open fire.”

The 4-pounder barked from its bunker, lighting up the prairie with the blast. I saw hundreds of Mexican soldiers, and far closer than any of us would have imagined. A few went down, but most were coming from the east beyond the gun’s best angle. They were in full uniform, with tall shako hats and crossed white straps over dark blue tunics. A few carried ladders, though most were armed with their Brown Bess muskets. For the barest moment, I thought I saw Colonel Morales standing near a colorful banner, waving his troops forward.

“Viva Santa Anna! Viva Mexico!”

the soldiers yelled, charging through the twisted monkey bushes toward the palisade.

The lunette’s 6-pounder fired, somewhat ineffectively, but the shearing red light showed scores of cavalry along the south road. They could not attack the fort on horseback; their mission was to cut down any of the Alamo defenders who might seek safety in flight. Hopefully my men realized there could be no such safety.

“Give it to ‘em, boys!” Crockett ordered, standing at the six-foot high wooden barricade with his 1873 Springfield. He put a foot up on the firing step, poked the rifle over, and shot the closest enemy, probably not more than twenty yards away. The man was thrown backward with such force that he knocked two of his fellows down, for at such close range, the Springfield has a devastating impact.