Curse of the Midions (11 page)

Read Curse of the Midions Online

Authors: Brad Strickland

“Going to be a wet day,” one of them observed.

“We'll have to hang the clothes inside, then,” the other returned.

Chatting, the two of them clanked off into the gloom, and as soon as they had gone, Betsy tugged at Jarvey's sleeve. “Now.”

They climbed over the step rail and ducked inside. The house was as silent as could be. Betsy led Jarvey up a dim stairway, illuminated only by a low gas night-light at each landing. The last stretch of stairs ended at a trapdoor in the ceiling. Betsy shoved at it, and it creaked open. She climbed through it, beckoning Jarvey to follow.

He pulled himself through, and together they let the trapdoor drop down silently. Jarvey fought an urge to sneeze. The air in the attic drifted thick with dust. “Don't move now,” Betsy said. “Get into a comfortable position and stay that way until all the maids leave for the palace.”

He stretched out, more or less, and soon dozed off. He didn't know how long he slept, but when Betsy shook him awake again, he could see. Thin daylight filtered in through ventilators in each gable of the steep roof. It didn't help much. Close to the trapdoor, a rampart of trunks and boxes stood, evidently hauled up to the attic in years past and then forgotten, for all of them wore furry coats of gray dust.

“They're out,” Betsy said. “I think they've all gone. Sometimes one of them is sick and stays behind, and then you've got to be really quiet. Today, though, it sounds like they've all left for the palace. We'll hole up behind the trunks and things. I'll go down to their kitchens and slenk some food for us.”

“Okay,” agreed Jarvey. He stretched and then explored. If they had everything behind the trunks to themselves, they had most of the attic. It felt warmâwarmer than the old Den in the alley, anywayâand seemed dry enough. Behind him, Betsy dropped through the trapdoor. Jarvey drew close enough to one of the big round ventilators to have a reasonable amount of daylight, and then he pulled out the Grimoire and studied its covers.

The way to find his parents, Zoroaster had said, lay in the Grimoire. He tugged at it, but it remained obstinately shut, as though the pages had been glued together. Jarvey took some minutes building up his nerve, then tapped the front cover with his finger and said, “Open!” in what he hoped was a commanding voice. Nothing happened. He took a deep breath and muttered, “I, Jarvis Midion, command you to open!”

The book seemed unimpressed.

Jarvey sighed and inspected the volume. The brass hinges gleamed dully against the pebbled, brownish red surface, and the brass catch could be flicked open easily enough. Still, regardless of what Zoroaster might have believed, the pages obstinately refused to open. Even for a Midion.

Clutching the book against his chest, his chin resting on the top edge, Jarvey thought about the weird moment when Siyamon Midion had given an order in a strange language. What had it been? Abracadabra, or something like that? Jarvey strained, but he could not quite bring back the strange syllables he had heard just before Zoroaster had barged in, yelling for him to beware the book. Jarvey could recall his own terror, the heart-stopping sensation of being turned inside out, of falling endlessly. He could see in his mind's eye long, crooked streaks of red and blue lightning. He could remember hearing shrieks and moans from the book's fluttering pages.

Not the words, though, not the spell that Siyamon had shouted just before the world had gone crazy. And if he could remember them, what then? He shuddered at the thought of the Grimoire opening once more, pulling him from Lunnon into some even worse place, if that were possible.

Zoroaster might have helped, but he had disappeared again, and Jarvey couldn't just wait around for him. There was only one other alternative. If he wanted to learn something about the magic that controlled the book, he had to find his way into the palace.

The trapdoor opened and closed, interrupting Jarvey's thoughts, and in a moment Betsy joined him, a look of triumph on her face. “Not too bad,” she announced. “They keep a larder of food here for night meals, for most of them eat in the palace kitchens by day. I took a bit from here and a bit from there, and no one's likely to miss any of it. Cheese, biscuits, grapes, apples, even some chocolates. Help yourself.”

They began to munch on the food. Jarvey tilted his head. “You're talking different,” he said.

She shrugged. “On the street you learns to talk street talk, cully. Away from the street, you can speak more properly if you wish.”

Jarvey didn't say anything, but he seemed to hear Charley's voice whispering inside his head: “Wonder what else she's been hidin' from you, mate.”

Impulsively, Jarvey said, “Tell me more about your mother.”

“Don't know much. I haven't seen her in ages, and I don't think I can find her, at least as long as old Nibs runs this town. What you and I have to do is take it away from him.”

Jarvey shook his head. “Why did he make Lunnon in the first place?”

She laughed without really sounding amused. “I've had a lot of time to think about that. Well, for one thing, he's old, really old. In the year 1848, he would have been about seventy. Now you say that in the real world, the world where he came from, a hundred and sixty years or so have gone by. So he's two hundred and thirty, right? In real time, he'd be long dead by now. In book time, he stops aging. He stays the same as he was when he came into the book. So he made this place in order to live forever. And why did he make it with the Toffs and the rest of us? Why, cully, people like Tantalus Midion ain't happy lest they have a boot on some poor unfortunate's neck.”

She leaned a little closer. “Listen, here's what I think. Tantalus couldn't make all of Lunnon. That's too big a magic even for him, even when he had the Grimoire. He could open the way to this place, but not create a city. So he found this world, saw it was the right proper sort of spot for what he wanted, and started in on his plan. He began to bring people here. First some of the Toffs, men who didn't want to die and who took his way out of the real world.”

“Magicians like him?”

“No, I don't think so. Least, nobody's ever seen anyone but old Nibs do magic in Lunnon. See, his Toffs can't do magic, but he can use 'em to drive the others. Then with the Toffs' help, old Tantalus kidnapped laborers, and maybe their wives and children. People to build, see? Lumber mills and brick mills and things, and then houses and places to make clothes and cook food and so on. And the children of those first laborers were born, and instead of staying babies, they grew up and became the next generation of poor folk and workers, and they had to be servants and slave in the mills. And old Nibs and the Toffs, why, they lorded it over all. Nibs is king here. He made Lunnon the way he remembered the old world, but put himself on top of the heap, like.”

“But only the Toffs are happy. Everyone elseâ”

“Everyone else doesn't matter,” she said flatly. “I doubt there's more than a thousand or two thousand like my mother. Transports, I mean. Everyone else was born here, and for us book time is real time.”

Jarvey thought about that. “Look, I'm trying to find a way to open the Grimoire. But if I do, what happens?”

Betsy grinned. “Don't know. But I

think

what may happen is that you'll open the door back to your world from this side. If you do, then maybe we can send Nibs back to the real world, and he'd be stuck there, because he wouldn't have the book to get back to Lunnon.”

think

what may happen is that you'll open the door back to your world from this side. If you do, then maybe we can send Nibs back to the real world, and he'd be stuck there, because he wouldn't have the book to get back to Lunnon.”

Jarvey licked his lips. “Zoroaster seemed to thinkâhe hinted that it might be the end of the world. The end of this world, anyway. Lunnon might disappear, everyone in it might die.”

She shrugged. “What's the odds? Go on living like we do, like rats under their feet, or have it all over with and die quick and clean?” Her green eyes almost glowed in the faint light. “I'd sooner go quick than linger on in misery.”

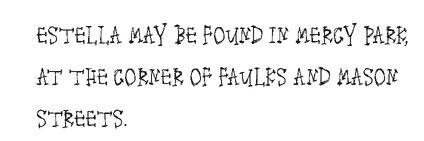

Something tickled Jarvey's leg, like an insect walking over his skin, and when he reached down to brush it off, he found the card he had fished out of his collar and shoved in his pocket. It had worked its way almost out, and when he looked at it, he saw tiny, spidery handwriting:

“What's that?” Bets asked.

Jarvey passed the card to her. “I don't know. I thought this belonged to Zoroaster, butâwhat's wrong?”

“Nothing.” Betsy crumpled the card. “Just rubbish. Look, you need to get some rest. It's been a hard day.” She made her way to the far side of the attic, where she sat with her back against a wall and her knees drawn up. Something about her posture warned Jarvey not to question her about the message.

Jarvey stretched out on the floor and tried to get comfortable, still wondering about the Grimoire and what he might be able to do if he opened it. If he sent Tantalus back, would the old man wind up in his own time, or in the twenty-first century? What would happen to Jarvey and his parents? He shivered at the thought of being thrust into the remote past, lost, still separated from his mom and dad.

“I want to go home,” he whispered, so softly that not even Bets's sharp ears could have heard the small, forlorn sound. “I just want to go home.”

Maybe Bets preferred a quick, clean end. Jarvey wanted life. Not only for himself, but also for his mother and his father.

CHAPTER 9

New Shirts

They hid in the attic for three days. By daylight they ate and slept, and some of Jarvey's strength returned as the aches and bruises healed themselves. Jarvey sneaked down into the stairwell after the first day and spent hours standing at a narrow window looking out toward the palace. He saw a high brick wall, with guard boxes on either side of a barred iron gate. Inside the boxes stood two unsmiling men at all times, beefy fellows who looked dangerous. That was where he and Zoroaster had emerged when Jarvey first arrived.

From the window's height, Jarvey could see a broad green lawn shaded by scattered trees, and beyond them a boxy stone house with arched windows and white shutters a hundred yards or so inside the gate. As far as he could see, the brick wall surrounded the grounds.

Sometimes people got in, though. In the mornings, small carts loaded with food rumbled up, and the guards would unlock the gate. The carts took a route that Jarvey couldn't quite see, a pathway around the inside of the wall, toward the back of the house. Once in a while a tipper, carrying a stack of papers, would approach and salute the men. They usually let the tipper inside, though once in a while a male servant dressed in black would come down from the house and take the papers through the iron bars instead.

Servants got in, of course. One evening Tantalus must have thrown a party. In the dim twilight, the house blazed with light, and twenty men and women, dressed as servants, walked up to the gate and were admitted. Before long, Toff carriages rolled up to the gates and let people out. Most were horse-drawn, but a few were pulled by teams of boys, dressed in silk uniforms but whipped like animals. That night the women who lived in the house were very late coming home, and the next day on a food raid Betsy was able to snare some delicious cake and some other tidbits.

On the first day, Betsy sneaked out and was gone for hours, returning silent and pale. When she remained withdrawn for hours, he began to worry. But whenever he asked, “Bets, is something wrong?” she would just shake her head and look away. Jarvey wondered where she had gone and what had happened, but if she didn't want to talk about it, he felt that prying would be wrong. Still, he woke at least once to the sound of Betsy's quiet sobbing. The sense that something bad had happened to her just added to Jarvey's uneasiness and to his growing sense that he had to find a way to get into the palace.

Toward the end of the third day, Jarvey made up his mind. He told Betsy, “I'm going to try to get into the palace somehow. I'll hide the book up here. If I get caught, at least old Tantalus won't get his hands on that.”

“You think you're ready for this?” Betsy asked.

Jarvey shook his head. “No. I'm not. But I can't think of any other way of trying to find my mom and dad. I'll never be ready, but I'm going to have to try.”

“Luck, then,” Betsy said. “I'll watch out for you. If you need help and you can think of any way to get word to meâ”

“You'll hear from me,” Jarvey said with a sick smile.

He left the next morning, as two girls went out for water. Jarvey had made what plans he could think of. One thing he had to have was different clothes. In Lunnon, you were a Toff, a servant, or one of the working poor. He wore the clothes of a poor kid, and he needed to look like a servant of some kind, at least a low-level servant. If you had a master, people let you alone.

Other books

Devils on Horseback: Nate by Beth Williamson

The Prince of West End Avenue by Alan Isler

Casa desolada by Charles Dickens

Birdie For Now by Jean Little

The Cedna (Tales of Blood & Light Book 2) by Street, Emily June

Endurance by Aguirre, Ann

Wanderlust: A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit

The Acolyte by Nick Cutter

Darcy's Trial by M. A. Sandiford

The Prodigal Comes Home by Kathryn Springer