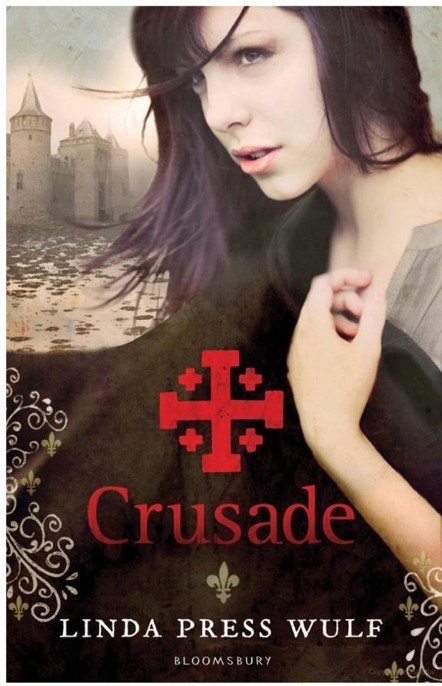

Crusade

Authors: Linda Press Wulf

Crusade

Linda Press Wulf

To my husband, Stanley, my stalwart companion on the long and rewarding journey

To my brother, Don, who inspired me to love history and helped to shape this book

Contents

The Children’s Crusade

Foundling. Orphan. Parish child.

All these names belonged to him but he didn’t want to belong to them.

Robert le Corde

,

Robert the Rope

, he was also called by the children in his neighbourhood, because of the knobbly scar, red and raised, that stretched like an unevenly coiled rope all the way from the outside of his eyebrow down to below his ear, at the jaw line. He had been trying to evade a crowd of such tormentors when he had scrambled up an ironwork gate and fallen, gouging the side of his head on the sharp iron points protruding from the top.

The barber-surgeon had shrugged his shoulders helplessly when he was called to tend to the unconscious little boy. The deep cut began too close to the eye for the barber to try sewing it together and all he could do was to give his most sagacious opinion: the boy would survive the injury if he didn’t die.

Robert had been carried into the nearby church, the only church situated among the higgledy-piggledy huts in this poor neighbourhood on the outskirts of the city of Tours. The city’s residents came here to dump their rubbish into the Loire. Children scavenged in the refuse on the riverbanks for anything that could be eaten or sold. Robert had slept on the floor of the church since he was a toddler, always at a little distance from the others who had no home.

After Robert’s accident, a kind priest had covered him with a blanket and brought him a bowl of gruel once a day. That was the extent of his nursing. There had been no wise woman to dress the wound with the whites of newly broken eggs or spread aromatic balsam to seal the hideous gash, no mother to massage the newly formed scar every day to press it flat. Whether he lived or died had been in the hands of the Lord. Whether there was minor or major scarring had been in those hands too.

Robert lived, but with a highly visible reminder of the accident. He flushed and averted his face whenever he was teased. Soon after the local children coined his new name, he took to wearing a loose, black hood over his head at all times, slipping it off only in the dimness of the church. He slept in front of the fire in the church kitchen and ate whatever food he was given in charity by the priests. He was often hungry but he never stole food like the other orphans in the town. This was not the result of adult influence or supervision. He had been born with an inviolable sense of right and wrong.

He also appeared to have been born with unusual intelligence. Hearing matins and vespers every day as he did, he was able to chant the liturgy by the time he was six years old, an accomplishment that was to change his life a year later.

One evening, the abbot of the large Abbey of Blois made an unscheduled stop just outside the church. An axle on his carriage had broken just as he was leaving Tours to return to the abbey across the river, and he was forced to take shelter for the night until the blacksmith could mend the axle in the light of day. It would be undignified for him to walk back to his hosts in the centre of Tours, and so he accepted the offer of a night’s accommodation in the church.

For a man with the abbot’s drive and ambition, this sudden waste of a night’s work was very trying. However, his iron self-control did not permit him to show his irritation.

He was invited to lead the priests at vespers.

‘Thank you, but I have a slight headache,’ the abbot replied. ‘I will be glad to pray quietly in a pew on my own.’

The truth was that the abbot intended to use the inconvenient delay to muse over some sensitive church business. Motionless in a dark corner, he was almost forgotten as vespers was chanted. A painter would not have been inspired by his stern face and rigid posture. But if a surgeon could have delicately sliced open the abbot’s scalp and revealed the man’s musings, he would have marvelled at the crystal precision of the abbot’s thoughts and the subtle shading of his calculations.

Viewers would look in vain, however, for the deep red pulse of emotion, or even the soft pink tissue of sentimentality. The abbot was not touched by the sight of a scar-faced little boy helping the priest at vespers, wearing a discarded habit so big for him that he had to lift the trailing skirt to walk. But his curiosity was aroused by the evident fluency of the lad’s Latin as he recited the liturgy of the hour. Only a few candles wavered in the deep gloom of the church, so the boy could not have been watching the lips of the priest: he had to have learned the lengthy service by heart.

‘Who has been teaching that child?’ he asked of the priest who was his host for the night.

‘Ah, you mean little Robert,’ the man said. ‘No one has to teach him. He has a memory more remarkable than any other I have encountered. He breathes in knowledge like air. He is a bastard, you know, a foundling left at the door of the church when he was but three years old, but I suspect that his father, or even perhaps his mother, did not come from the ranks of our illiterate congregation.’

The abbot asked no more questions, but after matins and lauds the next morning he called the little boy to him. The boy looked up timidly at the imposing figure in a severe black cloak.

‘I heard you chant vespers yesterday, and today you said matins and lauds alongside the priest, boy,’ the abbot observed without any preliminaries. ‘Can you recite them on your own?’

The boy did not reply directly but began to chant the Latin, perfectly, without hesitating over a single word.

‘What is thirteen plus seven minus three, boy?’

The boy’s face was blank. Clearly he had never learned the concepts of addition or subtraction. But when the abbot told him a complicated story of some boys playing with pebbles in the street, exchanging this one for two of those and losing certain numbers of their stones along the way, the boy listened with interest and then told the abbot exactly how many pebbles were in the pocket of each boy when they ended their playing for the day.

The abbot observed him silently for a minute, and then drew three letters on a dusty tombstone with his long finger.

‘Can you tell me the names and sounds of those letters, boy?’ he enquired.

‘No, Père Abbé, I cannot read yet. But I hope to find someone who will teach me one day,’ Robert answered eagerly.

‘This is a “b”, this an “a”, and the last one is a “d”,’ the abbot told him. ‘The first one takes the sound

b-b-b

, the second one makes the sound

a-a-a

, and the last one sounds like

d-d-d

.’

Robert’s dark eyes were focused intently on the streaks in the dust.

‘If you want to read what they say together, you make the sounds aloud.

B . . . a . . . d . . . B-a-d. Bad.

So the letters together say

bad.

Do you understand?’

Robert nodded vigorously.

‘Now, I will write a different word,’ said the abbot, printing

Dab

below the other. ‘You have to remember the sounds of each letter in the previous word. Then you will be able to read this word too.’

Robert examined the scribbling on the ground. He murmured to himself for a while, and then raised his eyes.

‘

D-a-b

. It says

dab

. Is that correct, Père Abbé?’

The abbot smiled thinly. ‘It is correct.’ Then he dismissed Robert, and he went to talk to the priest who had told him about the boy.

The mended carriage left the church courtyard that morning carrying a little extra weight. It was the boy’s first journey out of Tours and across the river. He was unnerved by the frigid manner of his august new guardian, Abbot Benedict, but also overwhelmed with joy at his sudden and unexpected good fortune. He was to live in a rich monastery called Blois. He was to eat three times a day – after waiting on Abbot Benedict’s needs first, of course. Most incredibly, he was to be taught to read and write so that he could help the abbot with his heavy burden of work. He was going to be educated to make him a credit to the abbot. He shivered with excitement and then gave a happy bounce on the springy seat.

‘Stop fidgeting, Robert,’ Abbot Benedict ordered. ‘Clasp your hands on your lap as I do, look straight ahead of you and keep still.’

Robert obeyed immediately. For this extraordinary chance, he would have jumped down to the road and run all the way alongside the unsmiling man in his black carriage. Certainly he could keep quiet and stay still, for years, if required.