Crude World (13 page)

This is the Trans-Ecuadorian Oil Pipeline System, known by its Spanish acronym, SOTE. More than three hundred miles long, it was built in the 1970s. In 2003 it gained a twin that doubled Ecuador’s export capacity, transporting Oriente oil over the Andes to the Pacific port of Esmeraldas. Ecuador now produces 500,000 barrels a day, with the largest portion of exports going to California. Whether it is irony,

parody or farce, one of the most environmentally conscious states in America depends on oil from a region that has suffered a catastrophe to provide it. Ecuadoreans are not amused; the pipelines are used as billboards for graffiti of the anti-imperialist sort, such as “The oil belongs to the people.”

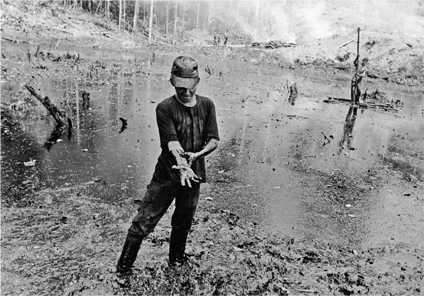

Oil spill in the Oriente region of Ecuador

These two pipelines are akin to aortas connected to a network of steel veins that move oil from the wells and processing stations spread over the humid flatlands. The smaller pipelines aren’t underground or routed away from roads and people, as they would be in a richer, better-run country. They rest on rickety pylons one or two feet high and just a few feet—or sometimes inches—from the roads. If you swerve into one of these pipes to avoid a pothole or lose control of your vehicle because you are drunk, you will create an oil spill. (It happens all the time.) Collisions are not necessary to create spills, because the pipelines are old and poorly maintained; they leak constantly. Until the 1990s, local residents say the environmental carelessness even involved the spraying of oil on dirt roads, so as to suppress the waves of dust that rose from them.

In the beginning, there was a misbegotten pioneering ethos. A new world was being carved out of the jungle; this was what progress was supposed to be. Hundreds of miles of new roads perforated the jungle, along with wells, waste pits, pipelines and processing stations. Boom-towns sprang up to house and entertain the thousands of construction and oil workers, and these insta-towns had the typical frontier accessories, including seedy bars, prostitutes and violence of the drunken sort. In a nod to the corporate creator of all these things, the regional capital was called Lago Agrio, which was the Spanish translation of the name of the American town where Texaco was born: Sour Lake. The transformation was accelerated by settlers who followed the oil roads. It is an irony of extractive industries that some of the damage they trigger is caused not by their own pollution but by settlement that is the result of opening up once-remote areas. “When a road is built, the settlers immediately come,” a rain-forest activist told me. “And when they arrive, there is no control on the cutting of trees. That’s how deforestation happens.” Ecuador’s government encouraged this process. To prevent

Colombia from invading the mineral-rich region and to relieve overpopulation elsewhere in Ecuador, the government gave land to anyone who cleared the jungle and started farming.

During extraction, water is pumped into oil fields to force out the crude, and when the oil comes up, so does “produced water”—a constant burp of oil, salt and metals that can include benzene, chromium 6 and mercury. In less spry fields, as much as 90 percent of the liquid that comes out of the ground can be produced water, not oil. Instead of reinjecting the tainted water into the reservoirs or filtering out contaminants—standard practices now, and done in other countries back then as well—Texaco dumped the brew into unlined waste pits or poured it directly into the Amazon’s rivers, according to environmental activists who are suing Texaco. More than 18 billion gallons of waste-water were disposed of in this way, they say, as well as 16 million gallons of oil—far more than the

Exxon Valdez

supertanker spilled into Prince William Sound. Texaco was lucky, because if you tip oil into Alaska’s waters, everyone knows about it and cares deeply. In the Amazon in the 1970s and 1980s, not so much.

In Ecuador, Texaco burned off at the surface the natural gas that accompanied the oil when it came out of the ground, just as Shell did in the Niger Delta. As I mentioned earlier, if the amounts are large, as they were in the Oriente, they can be deadly for the environment as well as for the people who live nearby. In the Oriente, the burning of natural gas was so unrestrained and unmonitored that there is no reliable estimate of the amount of toxins released into the air.

It may not be much of an exaggeration to say that the rain forest was Texaco’s rubbish bin. But that is not the worst part of the story.

In Lago Agrio I met Donald Moncayo, a leader of the Amazon Defense Front (also known as the Frente). Like any citizens’ group whose name includes the words “Front” and “Defense,” it was a no-frills outfit that operated out of a few chaotic rooms in a two-story building that had a warning sign at its entrance: “Site Under Surveillance.” In case a visitor wasn’t sure who was doing the surveilling, the sign helpfully showed an army tank. The Frente was involved in a multibillion-dollar lawsuit

against Chevron (which completed a merger with Texaco in 2001) and counted among its adversaries not just the American oil giant but the Ecuadorean military, which at the time of my visit had lucrative security contracts with Chevron and other oil companies.

Moncayo, who was in his early thirties, had been raised in Lago Agrio because his father had gone there to find a better life. As a boy, Moncayo swam in a river that had veins of oil; the locals were unaware of the health hazards of the dark goo that was showing up in their previously pristine waterways. Moncayo worked briefly in the oil industry, which was the largest employer in Lago Agrio, but soon left for the ranks of environmental activists. It was not a lucrative choice—Moncayo now lived in a wooden shack with no running water or electricity, and when I stopped by one day, a very large pig was napping by his front door.

It was time for my Toxic Tour—this is the term Moncayo uses to describe the inspections he arranges for journalists. You could call Moncayo my toxic guide. We bounced in my rented 4×4 over the red dirt roads that crisscross the feeble jungles around Lago Agrio, trundling past rickety homesteads made of salvaged wooden slats. Most of these shacks did not have water, electricity, glass windows or mosquito nets; they were glorified lean-tos in which people lived their entire lives, deriving no benefit and, in fact, much misery from the oil a few thousand feet under the earthen floors of their homes. They looked impassively at me, another gringo who would come and go.

Our first stop was a dirt field the size of a soccer pitch that had, at its center, a rusted wellhead. Moncayo said the well had been shut down in the early 1990s. No problem so far. He then led me to a pond fifty yards away that was filled with murky water in which I saw globs of oil. Oil that had leaked into the ground long ago, when the well was in operation, was finding its way back to the surface. Dirt had recently been thrown into the water to absorb the oil, but this was the work of Sisyphus, because it would never end. “Every so often, more oil comes out, and they put more dirt on it,” Moncayo explained.

We drove on for fifteen minutes, then stopped along a dirt road, where a farmer, Francisco Jiménez, told me an oil tanker truck had

jackknifed into a stream adjacent to the road. Because the tanker was too heavy to be pulled out, Jiménez said, the oil had been dumped out of the tanker and into the stream. Jiménez walked to the stream and stuck a shovel into the ground, pulling out a clump of wet earth. The soil was streaked with oil, and the stream, I noticed, was topped with a film of crude. Jiménez told me that Texaco workers came a few days after the tanker accident and put some of the coagulating oil into sandbags, but most of it was untouched, seeping deeper into the ground and into the streambed. The oil-soaked sandbags remained where they’d been filled, just a few yards from the water. The company’s workers could not be bothered to take them away, he said.

The tanker accident, Jiménez added, happened twenty years ago. The sandbags had been there for twenty years. Yet the pollution was still rising to the surface and was still alive in its unfortunate way. (Because the spill happened long ago and was minor in the grand scheme of pollution in the region, it was not possible to find a Texaco official who could deny or confirm it.) This was a reminder of one of the strange properties of oil: we may hastily bury it in the ground, but it does not disappear. Two things can happen. It may sink deeper, poisoning the groundwater, or it may rise to the surface, poisoning the water there. Or it may do both. We may wish to forget about oil, but oil will not let us.

To reach our last stop we drove down a dirt road that ended in a sickly, faded-green jungle; something was off. We walked a few hundred yards, pushing through the undergrowth, until we encountered what looked like a small, dark lake. It was actually a large pit filled with oil sludge that had the consistency of cookie batter. Where had the oil come from? It was dumped long ago, Moncayo said. Instead of disposing of spilled oil in an ecologically responsible way, Texaco would save money by pumping it into a tanker truck and driving the truck into the jungle, he claimed. With no one looking, the oil would be poured onto the ground, out of sight and out of mind.

“What would happen in Texas if there was a spill like that?” Moncayo asked, pointing at the black lake in front of us.

I said it would be cleaned up, quickly.

“We’ve been waiting seventeen years,” he replied.

If a curious mind wanted to know what a major oil company might do without oversight in the developing world, the answer was to be found in the Oriente. And a remedy, in the form of a multibillion-dollar lawsuit pushed forward by a Harvard Law School classmate of Barack Obama’s, could also be found there.

When Texaco discovered oil in the Oriente, Ecuador was a deeply impoverished country with a tiny industrial sector and no expertise in oil. It is only a small exaggeration to say that few Ecuadoreans, even the educated elite in Quito, could tell one end of a drill bit from the other. In the Oriente, Texaco’s representatives were dealing with illiterate Indians who did not even speak Spanish, the country’s official language. The first offering from Texaco, in exchange for permission from the Indians to look for oil, was a delivery of bread, cheese, spoons and plates. (The Indians threw out the cheese because it smelled so peculiar.) As in Nigeria and other underdeveloped countries, the foreign oilmen were met by an unsophisticated population that trusted their promises of good things to come.

Texaco eventually negotiated a contract that was typical in those days. It entered into a joint venture with a state-owned company that had been formed for the occasion; because Ecuador did not have a state oil company, one had to be created. Though it was a partnership, Texaco was the “operator,” meaning it managed all activities. Because Ecuador’s government had almost no expertise in the oil industry, it rarely questioned anything Texaco did. If Texaco said there was no problem dumping produced water into the Amazon, the government went along with it. In the early years of the venture, other than vague rules about respecting the health of the land and the people, Ecuador did not even have environmental laws for the oil sector. René Vargas Pazzos, a former army officer who presided over the state oil company in the early 1970s and was later minister of natural resources, said in an affidavit that Texaco had “complete autonomy” because the Ecuadoreans

involved in the industry and in its oversight were either clueless or powerless.

“All of the members of the government of Ecuador assumed that the technology employed by Texaco was first-rate technology,” Pazzos stated. “No one in the government thought that this petroleum giant utilized second-rate technology in Ecuador, including the dumping of production waters and other contaminants in the environment. No one ever questioned the practices of Texaco, for the simple reason that during all this time [no one] had the necessary information to question and oppose the practices which were chosen by an American company that presumably operated in an ethical manner around the world.”

By the 1980s, a gathering disaster had fully gathered. Not only had the land in the Oriente been spoiled; the country’s finances were ruined. The government had taken out billions of dollars of loans, on the assumption that it could pay them off with oil revenues, but when prices began to fall and a series of natural disasters struck the country, there was not enough money to go around. Thanks to oil, Ecuador had drilled itself into more than $10 billion of debt. The honeymoon with Texaco was over. The only good news was that Ecuador had slowly accumulated a moderate level of industrial expertise because some members of the new generation, sent to America for training, had returned home with engineering and other degrees. The state oil firm, a shell at its creation, was now capable of running the wells and pipelines that Texaco built. In 1992, as its joint-venture accord expired, Texaco left the country and handed over its facilities to Petroecuador.

This was not an entirely happy ending, because Petroecuador was not much better than its American godfather. The company cut corners as much as Texaco had, for the simple reason that the government, deeply in debt, needed every penny it could squeeze from its oil company. Instead of investing in better technology and safer practices, the government used oil revenues to pay off foreign debts and fund usual government operations (though in 1999 and 2000 the government defaulted on debt payments). Although Petroecuador has made some improvements in recent years, in the 1990s natural gas continued to be flared into the air, and polluted produced water continued to be

dumped into rivers and leaky waste pits. The Amazon, victimized by a foreign corporation, fared little better at the hands of its state-owned successor.