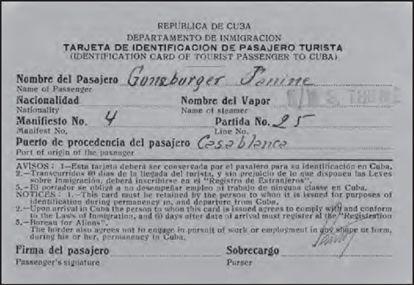

Crossing the Borders of Time (42 page)

The tourist identification card provided to Janine aboard the

San Thomé

for debarking in Cuba

The site, however, is easily reached today not only by ferry, but also by car through a short tunnel crossing under the rocky tip of the harbor where the forts of El Morro and La Cabaña, looking out to the ocean, once comprised the most powerful Spanish defensive position in the New World. Here, in colonial times, a large wood-and-bronze chain was stretched across the harbor each night to block foreign ships from reaching Havana. Guards at the massive fortress of La Cabaña sounded a cannon to signal that the harbor was sealed, preventing those already in port from sailing away under cover of dark.

On July 31, 1942, the New York–based immigrant newspaper the

Aufbau

publicly pleaded for mercy and justice on behalf of 450 refugees from Hitler’s Europe, the Günzburgers among them, still confined at Tiscornia after almost three months. The detainees included 250 passengers from the

San Thomé

as well as 200 from an earlier sailing arranged by the Joint. Passengers from that ship, the

Guinée

, also a Portuguese vessel, had been interned since April 9, about a month longer than the

San Thomé

group.

As of 2004, the street sign on Callejón Tiscornia provided the only indication of where the detention camp for Hitler’s refugees stood. The camp had been replaced by Cuba’s Instituto Superior de Medicina Militar

.

(photo credit 15.1)

“The captive refugees are surrounded by silence,” the

Aufbau

reported. “Every once in a while they hear rumors that their liberation is nearing, only to find out that what looked like a transitory period is developing into a state of permanence. They live without comfort, in overcrowded quarters, inadequately nourished, exploited by individuals who sense an opportunity to enrich themselves. Their spirits are low; they brood over their undeserved fate and find no answer.”

An internal report of the Joint’s Relief Committee condemned their condition with stark facts: “The facilities are entirely inadequate” for a population it described as including 88 children, 66 elderly, 168 women, and more than 100 men. “The great majority of the refugees live in dormitories in groups of 120 to 125 each; men and women are separated from each other so that there is no privacy of any kind.” Noting that the refugees could not understand the reasons for the indiscriminate internment of babies, children, the sick, the feeble, and the aged, the report warned, “We feel very strongly that there is a serious danger of a general breakdown of health and increasing signs of camp psychosis.”

Passengers from both ships were being held subject to “case-by-case examination,” the Joint in Havana explained to New York headquarters. “Rumors have been circulated to the effect that there were Nazis among these groups. To the best of our information, these are unfounded.” But getting the refugees freed from the camp involved complex financial, diplomatic, and political issues, and the American State Department, demanding “the most complete investigation of each of these cases,” seemed less than eager to help speed the process.

Initially promised release within days—

sí, sí, mañana, mañana

—the refugees gloomily waited with no sign of progress. For the Cubans, meanwhile, detaining these lost Europeans was proving highly profitable. The émigrés took no pains to disguise their goal to get out of Cuba and head for the United States the instant that their visas came through, so Batista’s regime was less concerned about building long-term relationships with them than with making the most of their stay on the island. The Cubans imposed camp fees of $1 per person per day, in addition to medical fees and so-called extraordinary fees that together amounted to $45,000 (equivalent to more than $600,000 in current value) by the start of July. At the rate they were paying the Cubans, families like Sigmar’s could have supported themselves both better and longer on their own in Havana, but the grossly inflated camp fees quickly devoured any money they had. “It is leading them into bankruptcy, no matter how well-to-do they may have been at the start,” the Joint reported. Along with detainees who could afford to contribute, the Joint was covering fees for half of the refugees, those deemed penniless, because the Cubans made paying the fees a precondition for eventual release.

Compounding money problems was the camp canteen, charging exorbitant prices in a monopoly market. The Cuban music that tumbled from loudspeakers over the camp and filled the store with upbeat, rhythmic songs of the tropics—with mambos and rumbas, drums and trumpets—failed to blot out the extent of the scam. Without competition, the bodega charged at least double the price for everything it sold to the inmates, who could barely subsist on rations alone. Camp doctors themselves advised refugees not to eat the meat or the fish served at meals because it was spoiled. Alarmed by the sight of refugees starving, the Joint distributed money to shop at the canteen for those who had nothing, and also sent in bottled water, 1,000 oranges, mangoes, bananas, or pineapples daily, 450 eggs, and sometimes sardines for the adults, as well as butter and milk for the malnourished children.

As weeks went by, the detainees banded together in a committee and elected leaders to deal with the Cubans and handle their interests with the Joint. Incensed by the canteen’s blatant price gouging, they organized boycotts with pickets, and their activism lifted their spirits; for the first time in years they effectively managed to wield influence and push prices lower. Food, however, was just one of a long list of troubles. Physically weak and emotionally spent, trapped in crowded and unhygienic conditions, many fell victim to heat, lice, bedbugs, and illness. Lacking the extra money required to stay in the clinic, those who were sick remained in the dorms, where crowding barely left space to walk between beds. The

San Thomé

group sparked an epidemic of a flulike disease that the doctors described as “seasonal grippe,” while whooping cough, enteric fever, hepatitis, and accompanying jaundice claimed many others.

PATIENT EXPIRED

was the sign that Trudi only half jokingly hung over a rope, trying to set up a makeshift quarantine around the metal bunk bed where Janine, stricken with hepatitis, lay moaning, yellow, and nauseous. But others quickly came down with it also, including an infant of just seven months, who sickened and died. “It goes without saying that such a child might have been saved under proper conditions,” the Joint concluded, despairing of the state of the camp. Yet because the child and his mother had shared a bed close to her own, Janine would not stop blaming herself for being the proximate cause of his death.

While the ill were not quarantined, the refugees’ contact with the rest of the ailing, war-weary world was so sharply restricted that the Joint summed up their status with one grim word: “incommunicado.” At the very moment they desperately needed to find out the fate of relatives elsewhere, make new arrangements, and reach out to friends or family already arrived in the United States for aid in securing visas and loans, they were kept isolated.

“Despite the fact that all mail is carefully censored all the way,” the Joint reported, the Cuban Ministry of Communications prohibited the delivery of critical mail, which might have provided important news, much-needed money, or documents that would help verify the refugees’ backgrounds. Nor did the Cubans permit the inmates to send any mail, a situation that punished Janine particularly, as her heart had been fixed, from the day the British in Jamaica confiscated Roland’s precious letter, on getting it back and writing to tell him where he could find her. More than sickness and bugs, heat and boredom and inedible food, her inability to make contact with him over so many months remained the overriding cause of her torment.

What if he’d been picked up in Lyon as an Alsatian? Already, the Germans might have him. Might have sent him to Russia. He could have been killed! She couldn’t bear to wait any longer to get to a post office, and so, when a tooth flared up, she begged the camp doctor for permission to make a trip to a dentist, never expecting to be kept under guard by two policemen throughout the time she spent in the city. She returned to Tiscornia minus a molar, but with her letter to Roland still in her pocket, as her minders would not allow her to send it. Nor would they let her attempt to retrieve any mail from Roland that might have been waiting for her, poste restante in Havana, as the British had promised.

Her only hope was to smuggle a letter out of the camp with someone she trusted, someone permitted to come and go freely. Her range of choices included just one, Sigmar’s cousin Max Wolf, a shrewd businessman who had managed to sail from France to Havana with his wife and children months earlier and had been held at Tiscornia for only a number of days. He was now living in a spacious apartment not far from the Malecón, where cooled by sea breezes, he could look north to his future over the Florida Straits and plan a path to profit on Wall Street. Meanwhile, having urged Sigmar to follow his route of escape to Cuba with the ultimate goal of reaching New York, he dutifully came to visit by ferry from Havana each week.

A heavyset man, Max invariably arrived at the gate exhausted and huffing from his arduous climb from the dock to the camp bearing food, cigars, and the latest newspapers. Once past the guards, with his face florid below his straw hat and under the shadow of his stubbly beard, Max would collapse in a chair in the open-air pergola under the trees that the refugees used as their common salon. Janine would watch him, quietly transfixed, as the floor gradually darkened around him, soaked by sweat that dripped down his legs and pooled at his feet.

His wife, Emma, never made the trip to the camp, but she regularly baked buttery pound cake and sweet fruit tarts for her husband to carry up to their friends. Her son Erich, on the other hand, often came to visit Janine, and it was the fondest desire of both fathers that their offspring might someday marry each other. Even in Lyon, he was the rival who most vexed Roland, knowing the power of Sigmar’s approval. Erich had come there to see the family on several occasions and before leaving France had inked a declaration of love in Janine’s little blue autograph book for the open appraisal of any reader, including Roland:

Was this the same Hanna of earlier times whom I had never bothered to notice in Freiburg? She has become a superb young woman! Now I cannot fail to appreciate her calm, decided, and serious character, and I realize too late my enormous stupidity in having left such a charming person so quickly. What more natural than for me to want, by any means, to return to Lyon to see her again and to find her as adorable as ever and to treasure an unforgettable memory of her?

Indeed, it was Erich whom Roland had in mind when he wrote in his parting letter to Janine that while it was normal for parents “to try to make you marry the man that they choose,” she should always remember that no one could force her. Still, it was not beyond her, after months of unavoidable silence that nevertheless grieved her heart almost as much as rejection, to seek to make Roland jealous by way of the letter she was hoping to send him. She therefore frankly included the news that Erich Wolf was also in Cuba and had been regularly—yes, devotedly—making the strenuous trip to the camp in order to court her. But how she could manage to mail it was far less clear.