Cross and Scepter (27 page)

Authors: Sverre Bagge

Late medieval art gives a similar picture. A large number of wall paintings have been preserved from the fifteenth and early sixteenth century in Denmark and parts of Sweden, mainly in local churches, and in recent years they have been the subjects of extensive iconographic analysis. There are the standard Old and New Testament scenes from the history of salvation, but these paintings excel in horrific depictions of the devil's temptations and the punishments in hell, an emphasis that echoes sermon

exempla

. The popular character of these paintings may indicate that local peasants had some influence on the choice of themes and thus may give some indication of popular religion, although there is no firm evidence to support such a theory.

These changes in religious expression, observed in art as well as in preaching, have often been explained as expressions of a new mentality of fear and hysteria brought on by the Black Death. No doubt, the frequent outbreaks of this terrible disease must have occasioned fear. Nevertheless, the idea of the entire period being dominated by terror seems extreme, the result of modern scholars imagining their own reactions to such disasters. Medieval people had after all far more familiarity with disease and sudden death than do we. Moreover, most religious expressions of the brevity of life and the terrible punishments in hell pre-date the Black Death. A gradual change in the direction of more vivid and emotional representations of these ideas from the late thirteenth century onwards should probably be understood instead as in part a change in rhetorical expression from abstract symbols to the concrete representation of visual reality, and in part as an attempt by the Church to draw the laity into a more active participation with religious life. These two explanations probably overlap in their impact, and both seem largely to be a result of the new piety introduced by the mendicants.

Sources on the religion of the ordinary people are meager. When it comes to the nobility, more information is available, but

it has not been explored extensively up to now. The numerous written sources from the later Middle Ages that originate with the nobility give the impression that the influence of the Church and religion was strong and pervasive. God is frequently referred to in correspondence, whatever the subject matter, in phrases like “by God's will,” “if God allows,” “may God protect you,” and so forth. Such expressions are of course not evidence of personal piety, but they do give some indication of the atmosphereâin the same way as their absence in present-day society reflects its secular character. Extant testaments show nobles leaving enormous sums to the Church, a generosity not always appreciated by society. Relatives clearly had interests that ran counter to the interests of the Church, and we know that they often contested what they considered excessive donations, sometimes successfully.

On the other hand, the value that the aristocracy placed on honor, revenge, and secular display must have been difficult to reconcile with Christian ethics (even if any apparent tension would have been somewhat eased by the fact that prelates and secular aristocrats often held the same values and acted in similar ways). Ecclesiastical criticism of aristocratic values was expressed in sermons and religious art attacking an obsession with the pleasures of this world and pointing to the narrow path that leads to salvation. We are badly informed about how this ethical conflict was experienced or possibly resolved by individual nobles or by the class as a whole. However, it is not simply a question of ideals versus practice. When failing to adhere to Christian norms, the medieval aristocrat often acted in accordance with a specifically aristocratic ethics and set of values. Thus, the noble had to maneuver between various ethical codes. Only on his deathbed would he fully embrace Christian values. With this in mind, one might regard great generosity to the Church as payment for persisting in a specifically aristocratic ethics and lifestyle. The issue may have been less troubling for women, who seem generally to have been

more pious than men. This may also have been the case in Scandinavia, but our information is limited.

Generosity to the Church should not of course be regarded solely as an expression of piety, for it could also amount to a display of the ostentation that was so essential a part of the lifestyle of the nobility. Funerals and death anniversaries were celebrated with particular pomp and circumstance. The rite of leading the horse of the deceased into the church at his funeral is an especially impressive example. The horse was guided to his master's coffin in the church, thus symbolically following him to his grave, and offered as a sacrifice to the church. The heirs subsequently redeemed the horse for a large sum of money. Despite all the aristocratic ostentation, the displaysâof pride, and care for the pleasures and wealth of this world, noble funerals nonetheless served to unite the ideals of the two estates of society, for they created an occasion for showing off piety as well.

Popular response to the message of the Church can mainly be traced indirectly. Miracles, pilgrimages, and the cult of the saints show ordinary people's attachment to the Church and Christianity, although some sources indicate that magic of a more or less pagan character was also practiced. Both Christian and magic rituals provide us with clear evidence of people turning to the supernatural to seek help in disease and various other life difficulties. They tell less about the search for God and salvation in the life to come. However, the imbalance is largely due to the character of the source material. Our major source, the extant miracle collections, are intended to prove the sanctity of particular persons by showing that they had performed “real” miracles, contrary to the normal workings of nature. Mere conversions or spiritual experiences were too ambiguous to be accepted as evidence, and, perhaps for this reason, were not recorded.

In his great book on medieval sainthood, André Vauchez distinguishes between “hot” and “cold” regions, according to their

ability to produce saints. Scandinavia as a whole must be considered relatively “cold.” Most of the saints venerated in the region during the Middle Ages were the common saints of Western Christendom as they appear in the Roman calendar. However, some local saints emerged from early on, and a few of them were even venerated outside Scandinavia. Most of these Scandinavian saints belong to Vauchez's northern type; i.e., they are people holding high office, who are mainly venerated for their miracles after death. Their official lives are usually impersonal and stereotypical, as well as fairly brief, while the main focus is on their miracles. The royal saints are typical examples of this. Whereas the popularity of the Swedish St. Erik and the Danish St. Knud seems to have been limited, St. Olav in Norway had great popular appeal, inside and outside the country, and a large number of pilgrims sought his shrine, particularly on his holiday on 29 July. By contrast, the southern type is a charismatic figure, whose reputation for sanctity is largely based on a remarkable lifeâSt. Francis is the best-known example. The preeminent Scandinavian exemplar of this brand of sainthood is St. Birgitta of Vadstena in Sweden.

A Scandinavian Saint

Birgitta was born in 1303 as the daughter of the

lagman

Birger Persson, a member of the highest Swedish aristocracy, while her mother, Ingeborg, was related to the royal house. At the age of fourteen, she was married to Ulf Gudmarsson, also a member of the top aristocracy. The marriage was happy; Birgitta bore eight children and lived as a mistress of a great aristocratic household. However, a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in 1341âa tradition in Birgitta's familyâbecame a turning point. The couple decided to live apart and devote themselves to religion. Ulf joined the Cistercian monastery of Alvastra, where he died shortly afterwards, in 1344, while Birgitta spent her time in prayer and contemplation in a house nearby. Birgitta had grown up in a pious family and been very religious throughout her life. She had her first revelation, of Christ's suffering, at the age of ten. Nevertheless, the separation from her husband and his death marked a radical change, as expressed in an episode told by her biographer, Peter Olovsson. Shortly before his death, Ulf had given her a ring, asking her to think of the salvation of his soul. A few days after his death, Birgitta took it off. When those around her pointed out that this did not indicate much love for her husband, Birgitta answered:

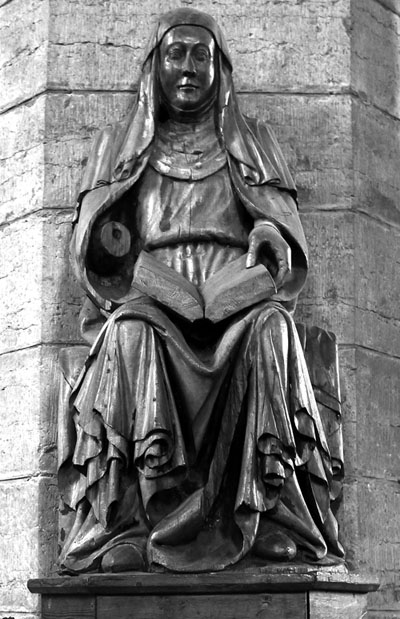

Figure 17.

St. Birgitta, sculpture in Vadstena Church (Sweden), c. 1390. There are several portraits of Birgitta, but this is considered to be the most authentic. Dept. of Special Collections, University of Bergen Library. Unknown photographer.

When I buried my husband, I buried all carnal love, and although I loved him of all my heart, I would not wish to buy him back ⦠against God's willâ¦. And therefore, that my soul shall lift itself to love God alone, I will forget the ring and my husband and leave myself to God alone.

After her decision to devote herself completely to religion, the revelations became frequent and directed her life. In 1345, she was told to found a new order and given detailed instructions for its organization, but the ecclesiastical authorities stopped her. In autumn 1349âthe year of the plague in Scandinaviaâshe left for Rome to celebrate the Holy Year 1350 and never returned. Now, her great project was to make the pope return from Avignon to Rome, but she was also working for the foundation of her order, which was finally accepted by Pope Urban VI in 1370, although the first monastery was not established until after her death, in 1384. Birgitta also intervened in Swedish politics and supported the opposition against Magnus Eriksson that led to his deposition in 1364. In 1372 she went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, where she became ill. She died in 1373, shortly after her return to Rome. She was canonized in 1391.

Birgitta had altogether more than seven hundred revelations, which were written down in four large volumes filling fourteen hundred pages, the

Revelationes celestes

(Heavenly Revelations). Birgitta either wrote them down herself and had them translated into Latin or told them to her confessor who wrote them down. In one of the revelations, she was ordered by the Virgin Mary to learn Latin, and, according to several witnesses who testified during her canonization process, she became quite fluent in the language, although she did not feel sufficiently confident to write her revelations in Latin herself. The revelations have a strongly sensual and visual character, with dramatic descriptions of the suffering of Christ and the saints, the pain of sinners in hell, and the ugliness and horrible stench arising from the devil and the sinners, all this very much in accord with the emotional and concrete character of contemporary art and sermons. On one point, Birgitta even directly inspired artistic representation. During her last pilgrimage, to the Holy Land, Birgitta had a vision of Christ's birth. She saw him lying on the earth while his mother worshipped him. This became a common motif in pictures of the Nativity in the following period. The revelations also testify to Birgitta's knowledge of doctrine and even lawâexpressed in descriptions of God's judgment of humankindâand include detailed and precise rules for her order. Despite her total break with her former life, Birgitta could draw upon her experience as the head of a large aristocratic household.

Claiming that one has received revelations from Christ and the Virgin Mary might easily have aroused suspicion in the fourteenth century, when the inquisition was in full swing and eager to persecute heretics of all kinds. And the danger was likely heightened when the revelations, like Birgitta's, were often critical of ecclesiastical as well as secular authorities, as for instance in the following outburst against the pope:

He is more disgusting than the Jewish usurers, a greater traitor than Judas, crueler than Pilate. He has devoured the lambs and strangled the shepherds. For all his crimes, Jesus has thrown him as a heavy stone into the abyss, and he has sentenced him to be devoured by the same fire that once devoured Sodom.

Birgitta was nevertheless accepted, and we can only suppose that her personality as well as her status must have been important factors. She was used to moving in high circles, and she had an excellent relationship to the higher clergy in Sweden, which may have helped her to acquire a similar network in Rome. Her advisers included the learned Nils Hermansson, bishop of Linköping, one of the wealthiest and most important dioceses in Sweden, and her confessor, Master Matthias, a leading theologian. Her later confessors, after Matthias's death, Peter Olovsson of Alvastra and Peter Olovsson of Skänninge, were also learned theologians. Thus, Birgitta had access to the best theological minds of her age, and her writings show that she made good use of them, keeping firmly within doctrinal orthodoxy. A widespread feeling of crisis in the Church might also have helped her, for she became part of a broad movement to reform the Church and bring the pope back to Rome.

Institutionally, the most lasting result of Birgitta's activities was the Birgittine Order, officially named the

Ordo Sancti Salvatoris

(the Holy Savior's Order), whose detailed rules were expressed in some of her revelations. Each monastery housed both monks and nuns, although strictly separated, under the leadership of an abbess. The original foundation, Vadstena in Sweden, became an important religious and cultural center with, among other treasures, the largest library preserved from medieval Scandinavia.