Critical thinking for Students (2 page)

Read Critical thinking for Students Online

Authors: Roy van den Brink-Budgen

Ken Stanborough accidentally dropped his daughter’s iPod Touch on the floor and, having noticed that it was then getting hotter and that vapour seemed to be coming from it, he threw it outside where ‘within 30 seconds there was a pop, a big puff of smoke and it went 10ft in the air’.

We would treat this evidence-claim in the same way as any other. This means that we would ask any relevant questions about it in order to consider whether it had any

significance. An obvious one would be, ‘Have there been other cases of exploding iPod Touches?’ Though the explanation for the exploding iPod is not something that we can necessarily explore (being a technical issue), we could look for possible inferences from the report. For example, ‘You should take care if your iPod Touch feels hot.’

We find these evidence-claims wherever we look. As we have seen, on their own they do nothing. They just sit there being stated. It is only when something is done with them that something happens.

REDICTION

-

CLAIMS

As well as claims of evidence, we also have predictions that ‘such-and-such will happen’. Such prediction-claims are normally based on some existing evidence-claims.

There is a baby already born today that will live until it’s 250.

In order to consider the possible significance of this prediction-claim, we would again ask questions. ‘Is this a one-off extra-long-living baby or is this baby an example of what will become a general trend?’ ‘Might a 16-year-old reading these words today still be thinking critically in 2160?’ We would need to ask explanation questions (Why is this possible?) before we could make claims of inference (So…). Thus the claim, ‘So we should scrap all this strange business of paying people pensions before they’re 75’, might follow from this prediction-claim (but might not).

In an important way, then, we deal with prediction-claims in the same way as we deal with evidence-claims. We ask questions about their significance. What do we need to know to give this prediction a significance? For example, in the one about the long-surviving baby, without doing this, the claim just sits there. We are clearly not meant to see it in the same way as the claim that ‘There is a baby born today that will live until it’s 85’. It’s meant to be significant. It shouts at you to be explained and then for at least one inference to be drawn from it.

ECOMMENDATIONS

What about claims that are recommendations? They also have to be seen in terms of possible significance. Look at the following recommendation.

We should take more exercise.

This again just sits there, without any significance unless and until someone gives it some. It might be that asking for explanations is important (What evidence-claims support the recommendation?). Questions can (and should) be asked about the words used. What is meant by ‘more’? More than what? How much is ‘more’? What is meant by ‘exercise’? Jogging? Going to the gym? Walking? Without having answers to questions like these, the significance of the claim is a problem. And until the significance is clarified, the claim cannot usefully be used to draw an inference (‘So you should join a gym.’).

RINCIPLES

A bit like recommendations are claims that are principles. We’ll spend some time looking at these in detail in Chapter 8, but we can note at this point that principles are general claims about what ought or ought not to be done.

Cheating in sport can never be justified.

You can see that this principle is no more than a claim. ‘Such-and-such is the case’ fits a principle exactly. It might be thought, however, that we don’t need to fret as much about significance. Perhaps, it might be argued, we don’t need to ask as many questions about principle-claims.

However, principle-claims are loaded with problems of significance. As with the recommendation about exercise, we need to ask lots of questions about the meaning of words. What is meant by ‘cheating’? Is it ‘breaking the rules’? What is meant by ‘sport’? Is poker-playing a sport? Is ‘eating as many burgers as you can in a minute’? What is meant by ‘never’? What about the problem of losing in football when you played for the national team in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (when losing would probably result in you and your family being shot by one of Saddam’s sons)?

We can see then that principles stand as claims whose significance needs testing by asking questions. Before we can usefully draw inferences from them, we have to ask these questions.

In this chapter, we have seen that doing Critical Thinking is very much about asking questions – questions about the significance of claims. These questions are very often to do with meaning.

• What

might

that claim mean?

• What

does

that claim mean?

• What does that word/term mean as it is used in this claim?

• Are there any problems with the meaning of words and terms in the claim?

We’ve so far been looking at claims where nothing has been done with them. We’ve looked at possible significance to see what

could

be done with them. But, if someone has already done something with a claim, we need to do the same sort of thing in order to assess what meaning they have given it.

• What meaning has been given to that evidence-claim?

•

Should

that meaning have been given?

We’ll look at this very big area of Critical Thinking throughout much of the rest of this book. Critical Thinking is indeed all about the significance of claims, very much including what people do with them.

We’re now going to spend time on a very important aspect of looking at claims – looking for and at explanations.

If you look at other books on Critical Thinking, you’ll find that explanations are consigned to a very minor role in the proceedings. For example, in Stella Cottrell’s book

Critical Thinking Skills

we find explanations dismissed in less than half a page out of the book’s 250 pages. This is bizarre.

The normal justification for treating explanations as having very little to do with Critical Thinking is that they aren’t central the study of ‘arguments’, which is what Critical Thinking is often seen to be all about. Here we go again. Unfortunately, the emphasis on arguments as the starting and end points of Critical Thinking can cause a lot of problems. Here it ends up obscuring the importance of explanations in the process of looking at the significance of claims. Putting explanations into such a minor position is a failure to understand their importance, and a failure to understand the importance of looking at the significance of claims.

However, before we turn our attention to the detail of explanations, it would be very useful to be clearer about what we mean by the term ‘inference’. You will remember that we used it in Chapter 1, and indicated its meaning by using ‘So…’. This focuses us well on what’s going on when we’re making or looking at an inference. When a claim is used to claim something else, then we have inference going on. For example:

Derek Bentley had a mental age of 11, so he should not have been hanged.

In this example, the first claim about Derek Bentley’s mental age is used to infer (draw) the second claim that he shouldn’t have been hanged. It can be shown like this:

Derek Bentley had a mental age of 11. → He should not have been hanged.

When we’ve produced a line of inference like this (claim → claim) we’ve got a basic ‘argument’, as the term is used in Critical Thinking. Arguments can get much more complex than claim → claim, but only because they can use lots of claims. However, if you just hold on to the idea of claim → claim, then you’ll know what we’re doing when we’re talking about ‘arguments’. It’s not much more complicated than that, so it’s astonishing how many writers and teachers spend so much time claiming it is.

The only other thing to note is that the process of claim → claim is designed to persuade others that this is the case. The person making the inference is saying ‘here is a claim, so this follows from it’. We might or might not agree, and then we’re straight back where we were in the first chapter, looking at the significance of claims. Does this claim mean what that person says it does? If it doesn’t, then claim → claim doesn’t (or might not) work.

With little or no pain, we have given ourselves a working guide to inference and thus ‘arguments’ as used in Critical Thinking. We’ll return to looking in more detail at inference and argument in later chapters. But let’s get back to what should be of great interest in Critical Thinking – explanations.

We saw in the first chapter that when we looked at claims, especially evidence-claims, we were often needing to ask questions about how we could explain the claim. In that chapter, we spent some time looking at the claim about the recent high proportion of left-handed US presidents.

We got so far with looking at the significance of the claim by asking questions to give us more information. But, in order to push further on with considering the significance of the claim, we need to look at possible explanations. Quite simply, unless and until we do, we can’t draw any inference from the claim.

Including President Obama, five out of the most recent seven US presidents have been left-handed. So …? (claim → claim?)

In Chapter 1, we saw that this claim had a possible significance in the light of the evidence that only about 10 per cent of the US population were left-handed. This possible significance very much pushes us to ask the question, ‘So how can we explain why so many recent US presidents have been left-handed?’

Here are some possible explanations.

1. Left-handed people think differently. They think intuitively (that is, they understand things without having to think them through). This might be useful for political success.

2. Left-handed people often had to deal with strong pressure from teachers to write with their right hand. Having to learn how to deal with difficulties like this and other aspects of a world dominated by right-handedness could make the

left-hander

a stronger, more determined person.

3. Because of the way in which their brains are ‘wired’, some left-handed people process language on both sides of the brain (unlike right-handed people). This could make them really good at making speeches which, in turn, would be useful in being elected as president.

4. Left-handed people tend to be more dominant, more self-centred, more pushy, all qualities that would be relevant for becoming president.

5. Left-handed people often go into specific jobs. For example, we find a relatively high proportion of left-handed lawyers, architects, artists, actors, and engineers. Barack Obama was a lawyer, as were the left-handed Presidents Clinton and Ford. The left-handed President Reagan was an actor. (An earlier left-handed president was Herbert Hoover, an engineer.)

Each of these could be possible explanations, and perhaps together they all add up to

the

explanation. But, as with claims, we need to ask questions of them.

For example, the second one – about left-handers being made to write with their right hand – wouldn’t fit Obama very well. This practice was still found in the 1950s and possibly even the early 1960s, but not beyond that, so he is too young (being born in 1961) to have been affected by it. (Interestingly, it might, however, explain why there were far fewer left-handed presidents before the ones that we’ve been looking at: perhaps they were required to be right-handed.)

The fifth one is interesting because it might provide an explanation which shows that it isn’t the left-handedness as such that’s the thing we should be looking at. Perhaps we should ask, ‘How many recent US presidents have been lawyers?’ (Answer = 3 of the most recent 7, or 42.86 per cent.) And what percentage of the US population are

lawyers? (Answer = 0.36 per cent) And what percentage of US lawyers are

left-handed

? (Possibly as much as 40 per cent!)

So here we have a new possible significance for the original claim we looked at. Given that lawyers have a relatively high rate of being elected as president, and given the higher rate of left-handedness in lawyers, we would expect that there will be a relatively high rate of left-handed presidents.

The claim about left-handed US presidents highlights well the importance of explanations in Critical Thinking. Explanations can focus us on the possible significance of claims. By doing this, they help us to look at what might be inferred from claims. (In the US presidents example, you might well have made the point that, in a way, all we’ve done is to solve one problem by creating another. OK, we’re clearer now about why there have been so many left-handed presidents. But why are so many presidents lawyers? Perhaps you can think further about that one.)

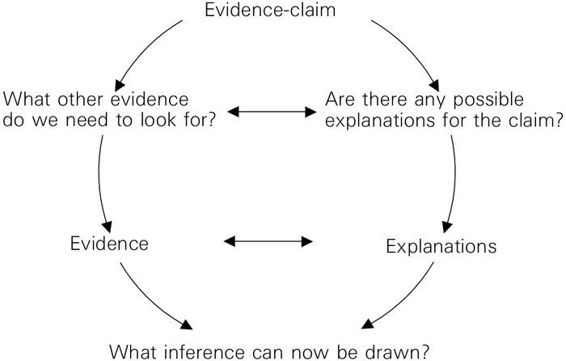

We can show the way in which claims, explanations, and inference are connected by using a simple diagram. Starting with an evidence-claim, we can see that our route to an inference lies through explanation. The relationship between evidence and explanation is shown by arrows going both ways, to emphasise that evidence is normally part of explanations, and that explanations often focus us on to what sort of evidence we need to look for.

A relatively high rate of recent US presidents have been lawyers + a relatively high rate of US lawyers are left-handed →

it is not surprising that a

high rate of US presidents are left-handed.

You will see that a possible inference has now been drawn (in italics). You could probably think of others. (

There will continue to be a relatively large

number of

left-handed

US presidents.

)

Before you leave this example, you might want to consider whether the other explanations that we gave are significant. But, before you do that, let’s just return to a question about the evidence on this subject that we asked in Chapter 1.

How many other countries have (had) left-handed leaders?

The relevance of this question should be clear. If there is a feature of left-handedness that tends to push left-handed people towards the top in politics, should we not find it in countries other than the US too? If we don’t find this, then we might have to look for an explanation that fits the US but doesn’t have to fit generally.

In the UK, there were only two left-handed Prime Ministers between 1945–2009: Winston Churchill and James Callaghan. That was two out of twelve, and they were in power for only about 12 per cent of the time. However, the present UK Prime Minister (2010), David Cameron, is also left-handed, so this makes three out of thirteen since 1945. In Canada, there’s never been a left-handed Prime Minister. In Israel, however, the Prime Minister is the left-handed Benjamin Netanyahu (as at October 2009). You can usefully research this further yourself, but there seems to be no other country with the same recent dominance of left-handed political leaders as the US.

You will remember that lines of inference (or ‘arguments’) are seen as having the function of persuading the reader/listener that ‘because such-and-such is the case, it therefore follows that…’ Some see a defining feature of explanations as being the opposite. They say that explanations don’t have the function of persuading us of something, but instead merely ‘account for’ something. However, this works only with some explanations.

Winter is the more common time for outbreaks of flu. This could be for a number of reasons. One is that, in winter, people spend far more time indoors so people can infect others more easily. Another is that, in winter, there is less sunshine, so the ultraviolet rays in sunshine are less likely to kill the flu virus.

In this explanation, the claim that ‘Winter is the more common time for outbreaks of flu’ is the claim that is being explained. The writer isn’t trying to persuade us that this is the case, in that presumably we’re not going to dispute it. (We might, of course, dispute the author’s explanation, offering other reasons as to why flu is more common in winter. Importantly, we’re now right back to the question of the significance of claims.)

However, there are explanations which aren’t just accounting for something. Such explanations deal with claims whose significance might be highly disputed. Here’s an example. There have been many explanations as to why the

Titanic

sank in 1912. Though few people are going to dispute whether or not the ship sank, there are considerable disputes as to the explanation or explanations. One recent explanation is that of the quality of the rivets used in the building of the ship.

The

Titanic

sank in 1912 because of the poor quality of the rivets used on the ship. According to two scientists, the shipbuilders Harland and Wolff were having considerable trouble getting enough top quality rivets for the three ships they were building all at the same time – the

Titanic

, the

Olympic

, and the

Britannic

. It was decided therefore to use what were termed ‘best’ rivets instead of the usual ‘best-best’. These poorer-quality rivets were less strong than the ‘best-best’. Furthermore, these poorer-quality rivets were used on the bow and the stern of the Titanic, with the stronger ones being used for the centre of the hull, because it was calculated that this was where the ship needed to be the strongest. Unfortunately, it was the bow of the ship that was hit by the iceberg, forcing the poor-quality rivets to fracture.

So what’s going on here?

This is an explanation of why the

Titanic

sank after hitting an iceberg. In this sense, it could be said to be accounting for why it sank. But it’s importantly doing something different. It amounts to an explanation of why poor-quality rivets would have caused the

Titanic

to be so badly damaged. To see it in terms of responses to a claim, let’s break it up into its parts.

Claim

: Poor-quality rivets were used in the building of the

Titanic

.Explanation

(also a claim): There was a shortage of high-quality rivets at the time of the building of the

Titanic

.Claim

(+ explanation): The poor-quality rivets were used on the bow of the ship. (The high-quality rivets were used in the centre of the ship because it was calculated that that was where the ship needed to be at its strongest.)Claim

: The

Titanic

’s bow hit an iceberg.Claim

/

inference

(as a result of explanations): The

Titanic

sank because of the poor quality of the rivets used on the ship.

We can see that the whole thing is a series of claims, with explanations forming a central part of what’s going on here. Though few people dispute that the

Titanic

sank after hitting an iceberg, it is not the sinking as such that is the centre of this sequence of claims. It is the explanation for it.

Here we have then an explanation which is very much ripe for Critical Thinking. We could ask questions about the claims being made.

What about the other two ships being built at the same time? Did they also sink?

The

Britannic

hit a mine in 1916 and sank. The

Olympic

carried on for 24 years, sailing until it was ‘retired’.

Has evidence from the wreck of the

Titanic

been found to support the weak rivets explanation?

Yes. It was always expected that a large gash in the bow would have been found, caused by the iceberg tearing into the metal. However, this is not the case. There are six narrow slits in the bow where the metal plates have parted, allowing water to rush in.

What other explanations have been given for why the Titanic sank?

There are plenty of these. They include the unusually large number of icebergs in April 1912, the lack of binoculars to see icebergs, and the calmness of the sea (so that there were no waves to be seen breaking on the iceberg). You can look for further explanations. (Indeed, it is very likely that the

Titanic

sank for a number of reasons.)