Criminal That I Am (15 page)

Read Criminal That I Am Online

Authors: Jennifer Ridha

When we hang up, I call Best Friend and burst into tears. She is as reassuring as she always is, but I can hear in her voice tones of disbelief.

“I just don't know how I will be able to handle prison,” I tell her. “And it's not just peeing in front of people. Have you heard about how women's prisons can be? Those girls are mean.”

For some reason, perhaps the image of me attempting to defend myself from the evil overtures of mean girls, this makes us both laugh. She tells me it's not going to happen. I tell her that I have seen the government do much more for much less. I know she agrees, but in allegiance to me she says it can't end this way.

I spend another sleepless night thinking about what will happen. Tossing and turning, my tears turn into anger. I am angry at myself. Angry for what I've done, where I've managed to end up. I am even angry that I bothered telling the truth, angry that the outcome here is possibly worse than had I just denied everything.

Tired of despising myself, I shift my ire to Cameron, drifting in and out of consciousness, hating him in ten-minute increments. I think back to the game I invented for his benefit, Who Would You Rather Punch? In this moment, there is no question that I would rather punch Cameron, closed-fist, square in the face.

Several days later, the angerâat myself, at Cameron, at everythingâbegins to fade. I allow myself to hope that this story will have a different ending. That the government will see that my ill-advised conduct was not born out of anything other than a misguided desire to help someone in a bad situation.

I repeat this to myself as though saying it will make it true. But I do

not altogether dismiss the possibility of the alternative. I decide to add kickboxing to my workout regimen. Just in case.

A

bout a week later, the day before my attorney is to make his presentation, I am lying on my couch. My face is slathered in a beauty mask, my feet are wrapped in moisturizing socks. This is actually an exercise recommended by my therapist called “self-care.” The practice has something to do with preventing the onset of clinical depression, but I think it is really meant to keep you from letting yourself go when everything around you is crumbling. Either way, it seems to work.

My afternoon of self-care is replete with the latest installment of Oprah's Farewell Season. I am elated when she announces that her guest for the day is Martha Stewart.

I have always loved Martha. I relish her intricate lessons on how to create all things handmade, something that Martha manages to do so effortlessly. Her cookbooks line my kitchen shelves and her craft books are stacked next to my sewing machine. During my case, in an attempt to distract myself, I put them to good use. By the time my case is over I will have sewn an entire new wardrobe, knitted half a dozen sweaters, and tried enough new recipes to feed a small village.

Today, Martha is talking about how to make the perfect grilled cheese sandwich and properly fold a fitted sheet. But before she does, she sits down with Oprah to discuss her time in prison.

Martha's criminal case is one that I followed with great interest, both because I am a dedicated devotee and also because the case was so very strange. Martha's crime took place at a proffer session like mineâperhaps, even, in the same stuffy conference roomâbut in a case where she had no real criminal exposure. In other words, her crime transpired in a place where she did not need to be. According to an article in

The New Yorker

, the reason why Martha's attorney ended up escorting his client to the scene of her crime is because he believed that declining to participateâin other words, pleading the Fifthâis not something you could suggest to someone like Martha Stewart. I find this reasoning odd, especially because corporate moguls like Martha exercise the right to remain silent all of the time. The Fifth

Amendment is as integral to the criminal process as flour is to pie, preferably one with a flaky crust.

During the proffer session, Martha apparently misrepresented the nature of a stock sale. And in a refrain similar to my own case, because of her public stature the government said it could not let the falsehood go.

So Martha catches a case. And when that case goes to trial, her best friend testifies against her. Back when it happened, I was disgusted on Martha's behalf. But thinking about it now, while my attorney is preparing to make a last-ditch effort to save me, I can't imagine being able to conjure the strength to endure such a betrayal. Unlike her pot roasts, Martha is as tough as they come.

Sitting on Oprah's stage, Martha has clearly moved past everything that's happened. She regales the audience with lighthearted tales of prison, how she managed to whip her entire facility into shape. I imagine myself serving time with Martha, learning at her side in the prison kitchen and during craft time. We swap stories from our cases and commiserate about the dismal décor in the U.S. Attorney's Office. I possibly get thrown in the SHU for following her around so much.

Her interview is winding down and it's almost time for grilled cheese. Then Oprah asks Martha whether she carries any residual shame for her crimes, and whether it weighs on her, what has happened, what she did.

I sit up at the question. I have grappled with this myself, wondering if I will ever be able to move on from all of this. I want to know if Martha has any advice as to how to remove this particular type of stain.

Oprah asks something like: Did you feel that you had let yourself down, or let other people down?

Martha pauses for a brief moment, and I hold my breath.

“No,” she says, and then talks about something else.

I rewind the exchange and watch it again.

I breathe a sigh of relief. Martha gives me hope that one day I will be able to let go of what I've done. When, just like her, I will be able to discuss what I've done with the same ease as making a grilled cheese sandwich.

I carry this moment with me for the remainder of my case, and for

long after. I consider it yet another invaluable lesson from Martha, and yes, a very good thing.

M

y attorney calls me after his presentation.

“What now?” I ask.

“We wait,” he says.

A

nd so, once again, I wait. I continue to be consumed with worry about my case, my fate. My thoughts also inevitably wander to Cameron, whether he is undergoing the same sequence of events, whether he is also waiting, whether he is wondering if I am waiting, too.

Our communication completely cut off, he still manages to show up in a strange dream. I am running through a hospital, knowing he is there, trying to find him. The hospital has an enormous screen announcing patient rooms and visiting hours in the same way that airports announce arriving flights. I scan the names but can't decipher any of them. I then rush from floor to floor, frantically throwing open patient room doors, asking hospital personnel where he might be found.

I'm about to give up when I turn a corner and see a door slightly ajar. I look inside. Cameron is lying on a hospital bed, barely conscious, visibly in pain. I'm terrified that he might be dying.

“Don't worry,” I tell him as I rush to his side. “I'm here, and I'm getting you a doctor right now.”

I run back into the hallway in search of a doctor. I'm shouting for assistance, but none of the doctors around me stop what they are doing. I finally see a doctor, a beautiful woman in a sterile white coat, looking at me expectantly. I go to her, grab her arm. I tell her that Cameron is sick, that he is in need of immediate medical attention, that I need her help.

Though I feel nearly unhinged, the doctor is calm, almost serene. She follows me into Cameron's room, looks at the manila file containing his chart. “Well, he's very sick,” she says.

“Do you think you can treat him?” I plead.

“I can,” she says. “But are you sure that you want me to?”

I look at her with confusion. “Why wouldn't I want you to?”

She gestures at herself, as though to indicate that in allowing her to treat Cameron, he may find her more alluring than me. That by bringing her to Cameron, I might ultimately be harming myself.

I don't bother considering such a stupid, selfish thought. “Are you kidding me?” I scream at her. “Don't just stand there!

Help him!

”

She quietly nods, says she will help him get better, that she will be back in a moment. With her words, relief washes over me. I run to Cameron, put my arms around him. I tell him that I've found him a doctor, that she will make him feel better, that his pain will be gone soon.

Cameron leans in close, turns his head toward my ear. As he begins to speak, I am startled. His voice is louder and clearer than anything else in the dream, as though someone has suddenly adjusted the audio levels in my brain. He sounds exactly as I remember, so much so that even in the dream I realize that his voice is something I have otherwise forgotten.

He says this: “Jen, I don't deserve you.”

And then the dream ends.

I

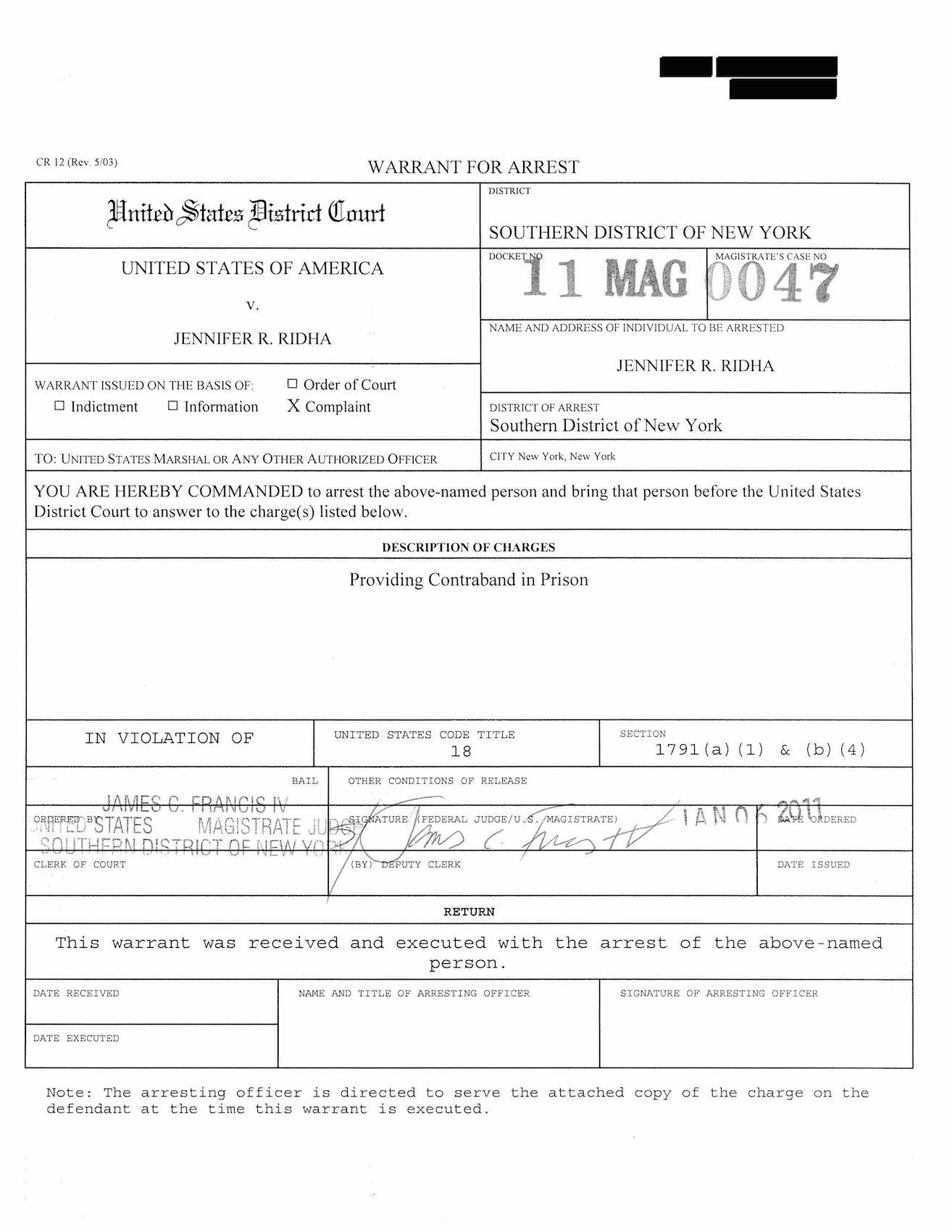

n November, the government finally decides what's to be done with me. They have agreed to enter into a deferred prosecution agreement that will result in the dismissal of my charges in six months.

In keeping with protocol, the government does not provide reasons for the change of heart. If someone told me it was because they determined my conduct was not in the end worthy of prosecution, I would think this might be true. If someone told me it was because disproportionate benefits were conferred upon me because of the stature and prowess of my attorney, I would think this might be true, too. Either way, I am grateful and relieved.

The general terms of a deferred prosecution agreement are these: for the next six months, I am required to remain crime-free. I must report in person to Pretrial Services on a weekly basis, my whereabouts recorded, my employment verified, my urine tested. A home visit will be conducted at my apartment to ensure that I live where I say I live. Also, specific to my agreement, I am required to continue seeing my therapist, a Âprovision

based on the not altogether unreasonable proposition that my conduct could have been prevented by regular therapy. After the six-month period passes, if all hoops are jumped, the charges will be dropped.

The next steps are these: I will have to formally admit my conduct to the government. I will have to surrender to the U.S. Marshals and then appear in court for my arraignment. During processing, I will be entered into the criminal justice system, my fingerprints and mug shot taken, my vitals registered. I will be held in lockup as the Marshals work through my paperwork. I will possibly be drug tested. I will then go to court, my rights read, my charges announced, my deferred prosecution agreement filed.

The proceedings, obviously, are open to the public.

I am ready to go into court and get this over with. Unfortunately, Pretrial Services has to approve me as someone they would be willing to monitor, and so there is yet more waiting.

In order to be approved by Pretrial Services, I have to provide answers to a questionnaire and collect a series of documents. It is almost Christmas by the time the questionnaire arrives. Eager to get the process moving, I scan through the form. But when I read what it asks, I begin to cry.

By this juncture in my case, I am prepared for the government to know everything there is to know about me. But I am not at all prepared for extensive personal questions about my family. I am required to provide their ages, occupations, and current whereabouts. It asks how long my parents have been married. It asks whether my father has ever hit my mother, whether anyone in my family has ever grappled with drugs. It asks if I have told my family about my criminal activity. It asks about their reaction upon learning of my criminal activity. It asks what my reaction was to their reaction. It goes on and on for pages.

Even though the answers are benign, I feel horrible that I have dragged my family into my wrongdoing, that my crimes are essentially their crimes, too. I feel an added layer of guilt because of my parents' beginnings under a totalitarian regime. I learned over the course of my childhood that the fears instilled by dictatorship don't easily subside. My father did not discuss the nature of his vote with anyone, not even his children, lest our big mouths broadcast it around town. When my

mother mistakenly believed my brother was a missing personâhe was in fact behind the football field with the rest of his class observing a fistfightâshe still refused to call the police, adamant that if she did we would be placed on some kind of list. And now, I am providing indelible details about their private lives to the government.

Given that the answers are required of my deferred prosecution agreement, my choices are few but to complete the questionnaire and to collect the dozen or so documents required. After the law school's Christmas party, I use the Xerox machine in the faculty lounge to copy all of the required documents. The next day, I pull everything together and send it off.

A few days later, I receive a message on my cell phone from my putative Pretrial Services Officer. Her voice is kind. She's calling to tell me she's received my materials and thanks me for providing them in such an organized manner. Apparently, these tend to come to her in a disheveled state, and I have just made her job much easier. She also wishes me a Merry Christmas.

Her message gives me an odd sense of pride. Perhaps it is the shame I feel in dragging my family through the court system with me. Or maybe it still means something to me to do a good job. Either way, I decide that this is proof that I still have something to offer to the world. I may have faltered in my duties toward society and family. But I am good at being a criminal defendant.