Criminal Poisoning: Investigational Guide for Law Enforcement, Toxicologists, Forensic Scientists, and Attorneys (13 page)

Authors: John H. Trestrail

3.10. THE TERRORIST AS POISONER

Certainly since the tragic attack on 9/11, the world has become conscious of the role that terrorism has played in causing deaths worldwide. Terrorists’ tools have mostly been explosives and guns, but poisons are also in their armory. There are numerous examples of radical groups who have been found to possess not only the knowledge of how to use poison, but also the actual poisons. What follows are just a few examples of these groups and the poisons that they used in their attacks:

• Order of the Rising Sun, Chicago, Illinois, 1972: typhoid.

• Red Army Faction, Paris, France, 1984: botulinus toxin

• Rajneesh Commune, The Dalles, Oregon, 1986: salmonella

• Minnesota Patriot’s Council, 1992: ricin

• Aum Shinrikyo Cult, Tokyo, Japan, 1995: sarin nerve agent • Anthrax Mail Tamperer, Washington, DC, 2001: anthrax

3.11. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF HOMICIDAL POISONINGS

In an attempt to shed some light on the poisoner, I have collected and analyzed 1026 documented known poisoning crimes in which the offender was convicted. This is a 51% increase from the 679 cases studied in the prior edition

Poisoners

57

Figure 3-4

of this work. What follows are the results of these analyses. As far as the geographic distribution of the cases analyzed, most were from the United States (404

[39%]) and the United Kingdom (255 [25%]), but numerous cases were from many of the world’s countries.

3.11.1. Most Common Poison Used

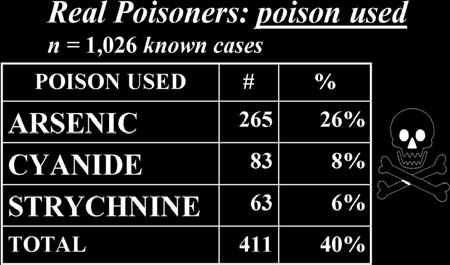

As can be seen in

Fig. 3-4

, the most commonly used poisons in order

have been the “Big Three,” consisting of 265 (26%) cases of arsenic, 83 (8%) cases of cyanide, and 63 (6%) cases of strychnine. These three poisons were involved in 411 (40%) cases of the 1026 poisoning cases analyzed.

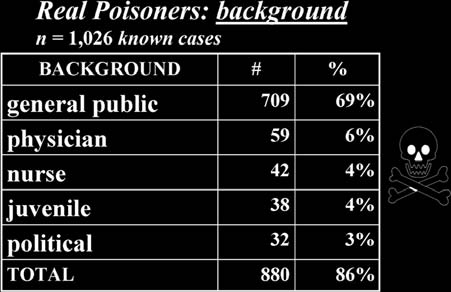

3.11.2. Poisoner’s Background

The analysis indicated that in 709 (69%) cases the vast majority of the offenders came from what could be called the general public, i.e., private citizens.

Fig. 3-5

presents the results.

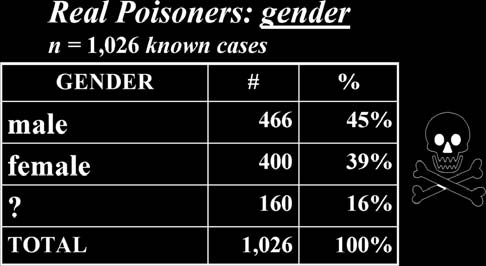

3.11.3. Poisoner’s Gender

The majority of the known offenders were found to be male in 466 (45%) cases; the 400 females represented 39% of the cases. This analysis must be looked at with the caveats that in 16% (160) of the cases the gender of the offender was unknown, and that these cases represent only incidents that were detected. It could be, once again, that females were more successful at remaining undetected in the crime (

see

Fig. 3-6

).

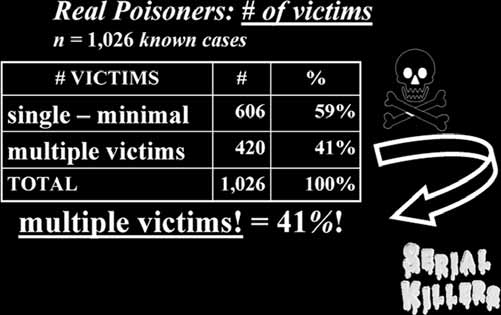

3.11.4. Number of Victims

In 420 (41%) of the cases, there were multiple victims, and these cases were divided into separate incidents. This indicates that in almost half of these

58

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 3-5

Figure 3-6

poisoning crimes, the poisoning offender was a “serial poisoner.” To quote Schonberg’s Law, “Anybody who gets away with something will come back to get away with a little more” (Schonberg, 1972). Certainly no other means of homicide produces this percentage of offenders with multiple victims. If there are no consequences to a behavior, it becomes chronic, and whereas most serial killers attack strangers, most serial poisoners attack those they know (

see

Fig. 3-7

).

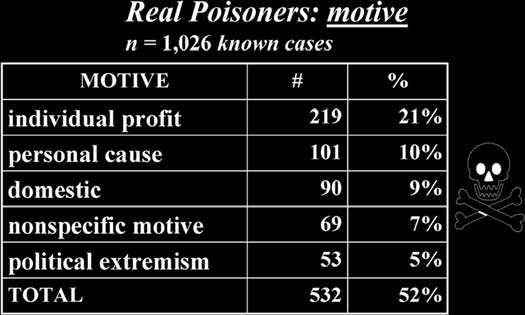

3.11.5. Poisoner’s Motive

Examination of the recorded motives for the crimes revealed that they usually involved love or money. Using the crime classifications in the

Crime Classification Manual

by Douglas and Burgess (1992), it was found that 219

Poisoners

59

Figure 3-7

Figure 3-8

(21%) cases were motivated by individual profit, 101 (10%) cases by a personal cause, and 90 (9%) cases by a domestic reason (

see

Fig. 3-8

).

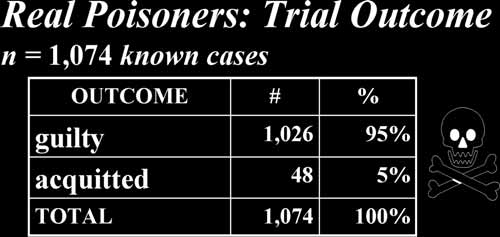

3.11.6. Offender’s Trial Outcome

In examining an enhanced set of 1074 cases of known poisonings, in 1026 (95%) of the cases, the suspect was convicted of the crime. Many of the remaining 48 (5%) cases were dismissed under a cloud of suspicion, but prosecutors were unable to prove the cases beyond a reasonable doubt (

see

Fig. 3-9

).

60

Criminal Poisoning

Figure 3-9

Figure 3-10

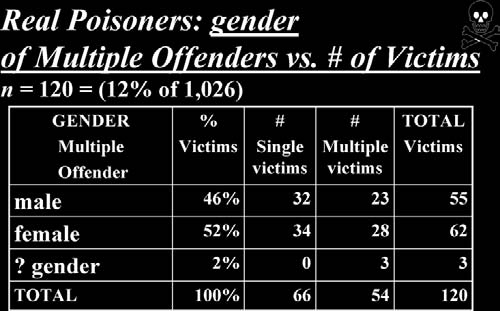

3.11.7. Multiple Offenders on Victim(s)

In 906 (89%) of the cases, only a single offender was involved in the crime. Multiple offender cases, although rare, are usually easier to convict, because there is the possibility of the two or more participants providing evidence against one another (

see

Fig. 3-10

). In the 120 cases involving multiple

offenders, 55 (46%) were male, and 62 (52%) were female, with 3 (2%) of unknown gender.

3.11.8. Gender of Offender vs. Number of Victims

It has been speculated by some that if the female is less easily detected in her crime, she would have a greater opportunity to carry out her deeds on

Poisoners

61

Figure 3-11

multiple victims over a longer period of time. In an analysis of the subset of 420 known cases that involved multiple victims, for female offenders, 43%

had multiple victims, yet for males it was 46%. This indicates that there is a slightly greater chance of males having multiple victims, but it might not be a significant difference between the genders (

see

Fig. 3-11

).

As can be seen from this chapter’s discussion of the poisoner, much more needs to be determined about this type of criminal offender. Remember, one can be a famous poisoner or a successful poisoner, but not both! To be able to lift the veil of secrecy that surrounds poisoners, it will take a concentrated and coordinated effort on an international scale to examine commonalities and possible cultural differences in the use of poison as a weapon for murder.

3.12. REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association:

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

, 4th ed., Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 2000, 714–717.

Douglas JE, Burgess AW, Burgess AG, et al:

Crime Classification Manual

. Lexington Books, New York, 1992.