Crime Time: Australians Behaving Badly (2 page)

Read Crime Time: Australians Behaving Badly Online

Authors: Sue Bursztynski

Tags: #Children's Books, #Education & Reference, #Law & Crime, #Geography & Cultures, #Explore the World, #Australia & Oceania, #Children's eBooks

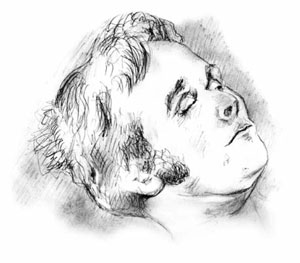

ALEXANDER

‘CANNIBAL’ PEARCE

W

hen Alexander Pearce, an Irishman, was transported to Australia in 1819, it was for stealing a few pairs of shoes. Today, that crime would incur a small sentence, but in those days, it could get you hanged. Alexander, however, was lucky. He was sent for seven years to the penal colony in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). In fact, some of Australia’s nastiest prisons were in Tasmania.

Alexander went to Macquarie Harbour, a prison so tough that prisoners were willing to kill each other, just so they could go back to the Hobart jail for a break before they were hanged. At Macquarie Harbour you could be punished for the smallest things – even for singing! Prisoners worked for twelve hours a day in winter, sixteen in summer, on very little food.

Everyone believed that escape was impossible. The sea destroyed small boats, you couldn’t swim to freedom and the bush around the settlement was thick. If, by some chance, you did get out, Hobart Town was 225 kilometres away.

In spite of all the risks, Alexander and seven other convicts decided to take their chances, first in a boat, then heading through the bush to Hobart Town.

One of the convicts, Robert Greenhill, was a former sailor and knew how to find his way. The others were Matthew Travers, Alexander Dalton, Thomas Bodenham, William Kennely, John Mather and William ‘Little’ Brown.

They hacked their way through the bush, but after nine cold, wet days, they had run out of food. Two days later, Kennely joked that he was so hungry he could eat a man. Robert Greenhill said this was a great idea. Human flesh, he said, tasted like pork.

The first victim was Dalton. He had volunteered to whip other convicts back at Macquarie Harbour and wasn’t popular. Greenhill hit him on the head while he was asleep. The body was divided up the next morning.

Brown and Kennely, fearing they might be next, returned to Macquarie Harbour. They made it back, but were so exhausted that both of them died anyway. At least they avoided being eaten!

The next victim was Bodenham, whose body was shared among the four survivors. Even though they saw kangaroos and emus, the runaways had nothing with which to hunt them, so Pearce, Greenhill and Travers attacked and killed Mather.

After a snake bit Travers, he made a very tasty meal for Pearce and Greenhill. Finally, Pearce took Greenhill’s axe while he was asleep and killed him. Taking an arm and a thigh, he continued on through the bush. From there on he was lucky. He met a shepherd, Tom Triffet, who was also Irish and was only too happy to help an escaped Irish convict. And Pearce learned that he wasn’t too far from Hobart Town.

A few days later, Pearce left with two bushrangers, but in January 1823, soldiers caught the three men. The two bushrangers were hanged, but not Alexander Pearce, who was sent back to Macquarie Harbour. He said he’d eaten the other runaways, but the police didn’t believe such a crazy story.

Other convicts at Macquarie Harbour now admired Pearce, because he had proved it was possible to escape. He might have got away with his crimes if he hadn’t developed a taste for human flesh. He escaped again, this time with a boy called Thomas Cox, who ended up as dinner. Pearce was caught with bits of Cox in his pockets and the boy’s body was in the bush nearby.

On 19 July 1824, Alexander Pearce went to the gallows, not at all sorry for what he had done. ‘Man’s flesh’, he said, ‘is delicious, far better than fish or pork’.

DID YOU KNOW…?

Until a few years ago, a loophole in taxation law allowed convicted Australian criminals to claim ‘business’ expenses, such as bullets, guns and other equipment needed in the practice of their criminal careers.

MATTHEW BRADY

THE GENTLEMAN BUSHRANGER

W

hen Matthew Brady was hanged in May 1826, thousands of women cried. He wasn’t exactly Robin Hood; if he gave to the poor, we’ve never heard about it. But he was good-looking and he had – well,

style

! Also, he was known for his courtesy to women and not killing without good cause. In fact, he only killed once and that man had deserved it. No, not quite Robin Hood, but close.

Matthew Brady started life in Australia in chains. We’re not sure why. It may have been for theft, or, according to some versions of his story, for forgery. Whatever the reason, he was sentenced to seven years and left his home in Manchester, never to return.

In Hobart, Matthew became an assigned servant. This was a system by which free settlers applied to have convicts to work for them. He hated being a virtual slave and tried to escape several times. During the first three years of his sentence, Matthew was whipped 350 times!

Finally, Matthew went to Macquarie Harbour, a penal colony on Tasmania’s west coast. No one escaped from there. That was until Alexander Pearce and seven others managed it in 1822. Of course, only Alexander Pearce had actually survived the journey, because he ate the others. But now convicts knew escape was possible.

In June 1824, shortly before Alexander Pearce was hanged, Matthew and thirteen other convicts escaped in a whaleboat, with soldiers shooting at them. Luckily for them, one of the men had been a Royal Navy navigator. He steered the boat to a place called Derwent.

There, they stole weapons and food and went inland to a place which is now known as Brady’s Lookout. It was safe. They lived there in hiding while they rode out to rob people. The gang became known as Brady’s Bunch.

Matthew nearly died when a man called Thomas Kenton, who had been receiving their loot, betrayed him. Kenton and two soldiers hit him and tied him up. The soldiers went to fetch more men. While Kenton was out of the hut, Matthew managed to burn through his ropes and grab Kenton’s gun.

He didn’t kill Kenton then. Matthew didn’t like killing. But Kenton lied about him, saying he had killed troopers. A year later, Matthew shot Kenton, as he was sneering that he knew Matthew didn’t kill people.

When Governor Arthur offered a huge reward for his capture, Matthew put up his own poster outside the Royal Oak Inn, offering a reward for Arthur’s capture.

Matthew’s men were loyal. One of the gang whom Matthew had kicked out for trying to rape a woman was captured, but refused to betray Matthew, even though he was to be hanged.

Over the next year, however, the men were killed off one by one, till only a few were left. The reward offered for Matthew had tripled to 300 guineas, around $700, which was a huge amount in those days. He had to get away before someone decided it was worth betraying him.

In late 1825, Matthew sent a message to the governor. He wanted to get out of the colony. If he didn’t, he’d capture an important settler, Richard Dry. But Arthur had done something Matthew didn’t know about: he had planted a traitor in Brady’s Bunch.

Matthew kept his word, capturing the whole house, with family and guests. He had a wonderful time and so did the women. He danced with them and sang for them at the piano. But a servant slipped out and brought soldiers to help. Matthew rode out with his men, wearing the hat of a Colonel Balfour, who had led the soldiers. It was typically cheeky, but this was his last success. He had been shot in the leg.

Governor Arthur’s spy, a convict called Cohen, told the soldiers where the gang was hiding. Matthew escaped, but his wound was still bad. He was caught by a bounty hunter called John Batman, who was to found Melbourne several years later.

Lots of people signed a petition to save Matthew’s life. It didn’t help. He had caused too much trouble to be allowed to live. While he was in prison, his admirers sent him flowers, food and fan letters. On the way to the gallows, women threw flowers at him.

Matthew bowed to the sobbing crowd, then accepted his fate.

DID YOU KNOW…?

The first crime in Australia happened only two weeks after the First Fleet arrived on 26 January 1788, with its load of convicts. Two convicts were tried for stealing. Other crimes happened only a few weeks after that.

AUSTRALIA’S FIRST BANK ROBBERY

S

ydney in 1828 was a very different place from today. Half the people living there were convicts. Not all convicts were kept locked up as prisoners are today. Many could walk around where they wanted as long as they went to work and turned up for church on Sunday mornings. Church was important. Any convict who didn’t come to pray could be locked up.

While many people were sent to Australia for crimes that would get them only a fine today, there were others who just kept on doing things they shouldn’t. The problem with keeping all those criminals in one place was that if anyone wanted to pull off a big heist it was easy enough to find experts.

James Dingle, who had been freed in 1827, had a wonderful idea. He knew about a drain under George Street, which led to the foundations of the new Bank of Australia, where rich people kept their money. Why not dig through to the bank? He discussed the matter with a convict, George Farrell, and a man called Thomas Turner, who had been involved in building the bank. Turner gave some advice, but dropped out of the plan in case the police suspected him. The thieves replaced him with a man called Clayton. They invited a safecracker by the name of William Blackstone into their plot. If anyone could make this work, he could.

The robbers decided to dig over three Saturday nights. They couldn’t do it on Sundays, because Farrell and Blackstone had to go to church, so they shovelled through the night. On the last Saturday, they were nearly through into the bank’s vault, where the money was kept. They really didn’t want to wait. So Dingle went to the convict supervision office and asked permission for Farrell and Blackstone to miss church that day. Whatever excuse he gave the clerk, it couldn’t have been, ‘They’re busy digging into the bank vault’. Anyway, it worked and they kept digging until Sunday evening.

After a break for sleep, they went back and took absolutely everything kept in the bank. At about 2.30 a.m., they were coming up from the drain with their loot when two policemen came past. They spoke to Dingle, who wasn’t carrying anything and told the officers that he had fallen asleep outside. One of the policemen was a little suspicious because it was a wet night and Dingle was too dry to have been sleeping out in the rain, but he let Dingle go.

On Monday, the robbery was discovered. A reward was offered for any information leading to the arrest of the robbers, but nobody came forward.

Now there was the problem of what to do with the loot. The bank notes were hard to spend, because the bank had records. The thieves decided to use a fence, someone who buys stolen goods and sells them to others. A fence called Woodward offered them a good price for the loot, then simply ran off with it. They did have some money left and they spent it gambling and drinking.

Blackstone was arrested for another crime and sent to Norfolk Island, a very nasty prison. He offered information about the robbery and Woodward, in return for freedom and a ticket back to England. The police agreed and in 1831 rounded up the other thieves. Dingle and Farrell were sentenced to ten years of hard labour. Woodward got fourteen years. We don’t know what happened to Clayton, who wasn’t arrested. Blackstone got his ticket home, but just couldn’t resist stealing from a shop before he went. So much for going home. Blackstone was sentenced to life on Norfolk Island, but somehow managed to get back to Sydney.

However, somebody wasn’t happy with him. In 1844, his body was found in a swamp in what is now the Sydney suburb of Woolloomooloo.

The Bank of Australia struggled on for several years after the robbery, but closed in 1843. The thieves had wiped it out.

DID YOU KNOW…?

Ikey Solomon was one convict who first came to Australia voluntarily. In 1827, Solomon was on trial for receiving stolen goods, but escaped while on his way back to prison: the coachman driving him there was his father-in-law! Solomon got as far as America, but when his wife, Ann, was sent to Tasmania for receiving stolen goods, Solomon went to join her. Everyone knew who he was, but he couldn’t be arrested without the paperwork, which had to come from England. The arrest warrant finally arrived and he was sent back to England for the trial he’d escaped. Then he was transported – to Tasmania! The writer Charles Dickens, who saw his trial, wrote Solomon into his novel Oliver Twist as a villain called Fagin.