Crime Seen (3 page)

Authors: Kate Lines

Shift work wasn’t an easy adjustment for me. I’d eaten my fair share of donuts, but I’d never developed a taste for coffee that the other guys drank so much of, particularly on night shift to help keep them awake. When the highways were quiet in the early-morning hours, Rick and I often sat at the side of the road in our cruiser and reviewed various criminal and provincial statutes that I needed to know. If he was driving and I happened to fall asleep in the passenger seat, he would sometimes drive off the highway and deep into a residential area. He then would wake me and tell me that if I was going to fall asleep, I had to take over driving and find my own way back to the highway.

My boss, Corporal Ted Stanford, was fifty years old with a head of thick white hair and salt-and-pepper moustache. Ted had three daughters and seemed to take me under his wing as his fourth. He had worked almost his entire career at Port Credit detachment. He was a kind-hearted, gentle man who took pride in having a shift of young, keen officers who needed no prodding to get out on the road and get the job done.

Ted even had some sympathy for the new rookie who had trouble staying awake on midnight shifts. I never had much of an appetite for eating lunch at three or four in the morning like the others on my shift, so I’d usually have a nap on the sofa in the women’s washroom. Ted’s office was directly across the hall from it. He would take note of when I went down and, forty-five minutes later, he’d softly tap on the door to get me back out on the road.

One night some of the guys came in off patrol before I arrived for my nightly nap break and set up a mannequin just inside the door of the women’s washroom. The arms were straight out from the sides with a bright yellow motorcycle cop’s raincoat overtop. The head was covered with a helmet. When I came into the ladies’ room, I had to switch on the light that was usually left on—that should have been my first clue. They heard me scream all the way to the other end of the detachment in the radio room where the guys were eating lunch. I could hear them laughing and a few chuckles came from Ted’s office as well. There was no nap that night—I couldn’t get my heart rate down enough to fall asleep.

I was soon performing my duties on my own. I met some of the nicest people running radar and when stopping cars for traffic violations. It was always a judgement call on what the best method was to deal with poor driving behaviour. A warning often seemed most appropriate. A small few didn’t seem to realize that calling me a “pig” or “bitch” was a sure way of earning them a ticket. But more often than not, I handed out tickets with people thanking me and telling me to have a nice day. I treated everyone with respect and almost all returned it back. One memorable exception was an evening when I got sucker-punched while arresting a drunken male pedestrian playing chicken with the traffic on the QEW. My pride was hurt more than anything. Thankfully Rick was with me and along with the help of two motorists we had stopped for driving infractions my roadside wrestling match was brought to a quick end. (All the two drivers received from me that night was my deepest appreciation for their assistance.)

I always wanted to treat people fairly. One early morning I was just about to finish my night shift when a car ran a red light right in front of me. I went after it and, when stopped, asked the driver my usual request for “driver’s licence, ownership and insurance, please.” As the driver complied, he told me he was dealing with some health issues, the breakup of his marriage, problems at work, and on and on. He even became tearful. I expressed my condolences for the difficult time he was having—but he got a ticket anyway. His sad tale just didn’t quite ring true to me.

At a friend’s house party in Toronto a few weeks later I joined a small group of people I didn’t know. One of the ladies was saying that a guy she worked with always used a “big sob story” when he got caught by the cops for doing something wrong. Apparently he never got charged because the cops always felt sorry for him. But a couple of weeks ago he came in to work outraged that he’d gotten stopped by some bitchy female cop after blowing a red light. For the first time the story didn’t work and he got a ticket. I just smiled.

One hot summer afternoon another officer and I were catching up on some paperwork in our air-conditioned detachment office. We were dispatched together to get out on the road right away and observe for a bank robber. A zone alert had been issued giving his and his vehicle’s descriptions and that if stopped to treat him as armed and dangerous. As was standard procedure in such calls, we took a shotgun with us and stowed it in the trunk.

We weren’t out on the road long when we saw a car that matched the description driving on a four-lane street. We turned on our gumball-red roof light and siren and the driver pulled over onto the shoulder of the road with us pulling in behind him. When I got out I grabbed the shotgun out of the trunk. As often happened, rubberneckers slowed down traffic to a crawl. My partner came up to the vehicle on the driver’s side and I proceeded on the passenger’s side. As we got closer to the car we both realized at about the same time that it didn’t exactly match the car description we were given, nor did the driver match the bank robber’s description. My partner spoke to the driver through his open window to explain why he was stopped. The passenger-side window was up so I opened the door to add my apologies. As I was opening it the driver yelled, “No!” just as six very expensive-looking Siamese kittens jumped out and scampered past me down into the ditch.

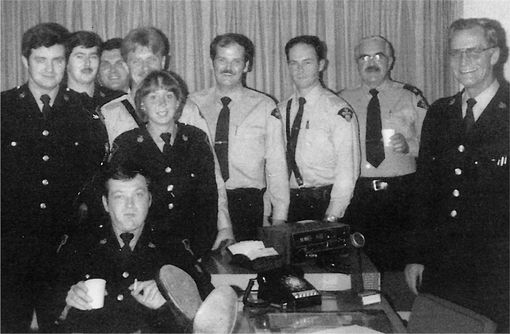

Standing: Bruce Pritchard, Ross O’Donnell, Mike Watters, Chris Newton, me, J.D. Cromie, Rick Walsh, Ted Stanford, Roy Wilkinson; Seated: Ken MacPherson

With the shotgun still tucked under my arm, I went after the escapees, calling, “Here kitty, kitty.” Unfortunately with the heat all the cars going by had their windows down and could no doubt hear me—I can’t imagine what they thought was going on. I was finally able to gather up all of the kittens and return them to their relieved owner. After returning the shotgun to the trunk, I got back into the cruiser and said to my partner, “Don’t say a word. Just drive.”

Ontario was the first province in Canada to require vehicle occupants to wear lap seat belts. Even though the law had been in force for several years when I became a police officer, there was poor compliance. Many times I gave a warning about a traffic infraction, but rarely passed on the seat belt violations. I had seen first-hand too many serious injuries or deaths resulting from people not wearing their seat belts.

The scene of a traffic accident was the one place that people were usually happy to see me. I responded to one where a young family on a camping vacation was rear-ended by a speeding car. Their eight-year-old son in the back hadn’t had his seat belt on. His parents had not moved him since the crash and were frantic when I arrived. I found him crumpled up on the floor of the back seat. His back and legs were badly injured from the impact. The father told me and the ambulance driver, “The sound of your sirens was the sweetest sound I have ever heard.” Sadly, from what I saw, I don’t think the boy would ever walk again.

When we uniformed police officers had to awaken families in their homes in the middle of the night, we were well aware that our presence would be far from welcome. The OPP delivered news not only of traffic fatalities, but also those relating to homicides, suicides and accidental deaths. When we knocked on the door they immediately knew it wasn’t going to be good news.

You could never anticipate what the response to the bad news would be. One thing that was likely was that they would remember every detail of what you said to them for the rest of their lives. You had to be very clear that given what you knew to be true—you were certain that it was their loved one that had died. Some wanted to think it was somehow a mistake but you had to tell them the cause of their loved one’s death and the circumstances as best you could. With encouragement, most would contact another family member or friend to come and be with them. We always sat with them until they arrived. It was the worst-possible assignment and you wanted to do your best-possible job.

On one occasion I was the lead investigator in a fatal single-motor vehicle collision. It occurred at about 1:30 a.m. on a fairly quiet stretch of highway. I was on patrol in the area when I got a dispatch call for a 10–45 (fatality). I was there within minutes. Pieces of the car were strewn about on the highway and in the ditches. The largest piece was the rear axle and an attached portion of the trunk. The partially decapitated body of a male driver, of what was once a Chevrolet Camaro, was in the grass median. Witnesses said this car and another one seemed to have been racing down the highway at speeds likely in excess of 160 kilometres per hour. The Camaro driver lost control and hit a series of cement bridge posts, breaking further and further apart with each impact. The other driver never stopped.

Rick and several other officers attended the scene to assist me with interviewing witnesses and taking scene measurements and photographs. I obtained the dead man’s identification from his jeans pocket and realized his home address was just a few kilometres away. He was three weeks shy of his twenty-first birthday. The coroner arrived and officially pronounced him dead. A funeral home came to collect the body.

It was then time for the horrible task of visiting the residence listed on the driver’s licence. I asked Rick to come with me and we arrived at about 3:00 a.m. We parked in the driveway and went to the side door where a light had been left on, probably for the young man we had just left. I knocked several times and a middle-aged man answered the door. I introduced myself and Rick and requested that we come inside. I asked him if he knew the name of the young man and he said that he was his father. I asked him if he was alone and he said that his wife had just been awakened as well. I asked him to get her as I wanted to talk to them together. The two returned, both still in their pajamas, and I told them the news that their son had been killed in a car accident. They said they had just seen and talked with him a few hours earlier. I told them again that I was sure it was him. The young man’s father just stared at me in disbelief. His mother became hysterical and inconsolable. We encouraged the father to call a relative, which he did. Through his tears, he asked a few questions about how the accident occurred and I told him what few details I knew. I dreaded that either of them might ask if they could see their son and his mother eventually did. I was at a loss for what to say, responding only that it was not possible at that time. We waited with them in the living room for the arrival of other family members. It was gut-wrenching. After their relatives arrived Rick and I excused ourselves, letting them know we would return later in the morning.

We attended the hospital morgue to view the body and were then sure that the confirmation of identity that was required would be impossible through any facial recognition. When we returned to check in with the family we found a cousin there who was agreeable to accompany us to the morgue to spare the family the task of identification. On the way to the hospital we explained the circumstances. He advised us that he had spent many summers at a lake swimming with the deceased and knew that he had several birthmarks on one shoulder. At the morgue the body was draped in a sheet. Rick and I stood on each side of him, holding him steady. The sheet was pulled back to show the shoulder area and he was able to identify the birthmarks as those of his cousin. He was very distraught afterwards, but acknowledged he was glad that it was him that came and not the parents. We returned him back to the home. I had been putting off the one last conversation that I had to have before I finished my shift. I spoke with the father privately, hoping that somehow having had a few hours to have the initial shock sink in, he would now be able to cope with the further details of his son’s fatal injuries. Or maybe it was just me needing the time to get up the courage to tell a father that he would not be able to see his son’s face one last time. Those were the worst few minutes of my life.

And then, after seventeen hours of work, I went home and cried myself to sleep.

In 1979 I was living on the eighth floor of a condominium in Etobicoke, west of Toronto. On November 10 I was home all Saturday evening and turned off my television just before midnight. I didn’t want to stay up too late as I was starting day shift the next morning. As I shut my bedroom blinds, I glanced out the window and saw the orange glow of what seemed to be a large fire in the west, about ten kilometres away. I drifted off to sleep thinking my fellow emergency responders in the Mississauga Fire Department likely had a long night ahead battling some type of industrial fire.

I didn’t open my blinds before I left for work the next morning but as I drove toward the office I could see smoke still billowing from the area of the fire I’d seen the night before. When I arrived in the parking lot at work it was full of marked police cars from other southern Ontario detachment areas. Getting out of my car I could smell the smoke and a strong chemical odour. Our small detachment office was crammed with officers and we were soon briefed that at 11:53 the night before a train had derailed in an industrial area about five kilometres northwest of the detachment. Part of the derailed load included “dangerous commodities” cars, one being a load of ninety tons of chlorine gas. Forty-five thousand Mississauga residents were already on the move following overnight precautionary evacuation orders. There would be no tickets handed out or arrests made that day, or for the next several days.