Creature from the 7th Grade : Boy or Beast (9781101591833) (12 page)

Read Creature from the 7th Grade : Boy or Beast (9781101591833) Online

Authors: Andy (ILT) Bob; Rash Balaban

Â

I SMELL A RAT

BANDITOES AND ONE-UPSTERS

are voting today to decide whether I will become socially acceptable at long last, or remain stuck for eternity on the absolute lowest rung of the popularity ladder. Sam and Lucille and I still aren't speaking to each other. Principal Muchnick keeps following me around to make sure I don't break any more rules. And everywhere I go I see Craig Dieterly lurking in the shadows, waiting to spring out and teach me a lesson I will never forget. No wonder my stomach hurts.

“Show me where, Charlie?” Nurse Nancy asks.

“Here.” I point to my distended belly. “It kills. I can't stop burping. And I feel like I'm about to throw up.” I am sitting on my crate in Nurse Nancy's office feeling sad and lonely and sorry for myself.

“Oh, dear,” she says. “You'd better lie down.” She motions to the cot in the corner of the room.

“I'll just sit here, if that's okay. I'm a little big for the cot.” I couldn't squeeze myself onto three of those things.

Nurse Nancy drags over a large wastebasket and places it beside me. “Just in case,” she says. “I'll be right back. Don't move.” She puts a cold compress on my forehead and hurries out of the room. It actually does make me feel a little better. Principal Muchnick pokes his head through the door.

“What's up?” he asks. I point to my stomach and moan. “You'd better not be faking again, that's all I can say, Drinkwater. Feigned illness is an official no-no. Section eight, paragraph three in the rule book.”

I burp loudly. It smells pretty bad. Principal Muchnick is out of that room faster than you can say “mutant dinosaur burps are disgusting.”

Soon Mr. Arkady glides effortlessly into the room, followed by Nurse Nancy. “You are lookink terrible, Mr. Drinkvater,” he says. “Stick out your tunk.”

“My what, Mr. Arkady?”

“Tunk,” he repeats. “Tunk!” And then he sticks out his tongue and points to it.

“Are you sure, Mr. Arkady?” I ask.

“Don't be shy, Mr. Drinkvater. Vee have all seen tunks before.”

I stick out the first few feet. Nurse Nancy turns a sickly yellow and looks like she is going to pass out. Mr. Arkady reaches into his white lab coat and quickly slips on latex examining gloves. He carefully explores the tip of my tongue. “Hmm . . . lean beck, pleace.” He palpates my big round stomach. “Does this hurt?”

“A little, sir,” I reply.

“Open your mouth and say âahh.'” He takes out a little flashlight from his lab coat and peers into my throat. “Very interestink.”

“What's wrong with me, Mr. Arkady?” I ask.

“A little acid reflux, maybe, Mr. Drinkvater,” he replies. “Nuthink serious.”

“Is there anything I can do about it?”

“Sure,” he answers. “Eat less. Cut out fatty foods. And reduce stress leffels. A saltine cracker at bedtime can do vunders.” He reaches into his lab coat again and pulls out two white tablets. “Take these. They vill help.”

“What are they, Mr. Arkady?” I ask.

“Tums. They cause tremendous farts in chimpanzees and lizards, so vatch out every-buddy.” Nurse Nancy runs from the room. Mr. Arkady tosses the tablets into my waiting jaws, takes out a soft cotton pad, and begins rubbing my belly with it.

“Sometimes it is difficult to be a teen-itcher,” he says. “The stress of adolescence can be terrible. Alvays tryink to fit in. And feelink socially unacceptable. Phooey. Who needs it? You must relax. And breathe dipply. Every-tink vill be okay. I guarantee it. Please stop vurryink.”

“Thanks, Mr. Arkady,” I say. “I'm feeling a little better now.” Mr. Arkady really gets what I'm going through.

“That's good.”

“But I'm awfully sleepy.”

“That's because I am rubbink your belly.”

“Are you hypnotizing me, Mr. Arkady?” I ask.

“I hope so, Mr. Drinkvater.”

“It's vurking. I mean working,” I say, as my eyes begin to close and my head slumps to the floor.

“You vill feel much better ven you avaken,” he whispers.

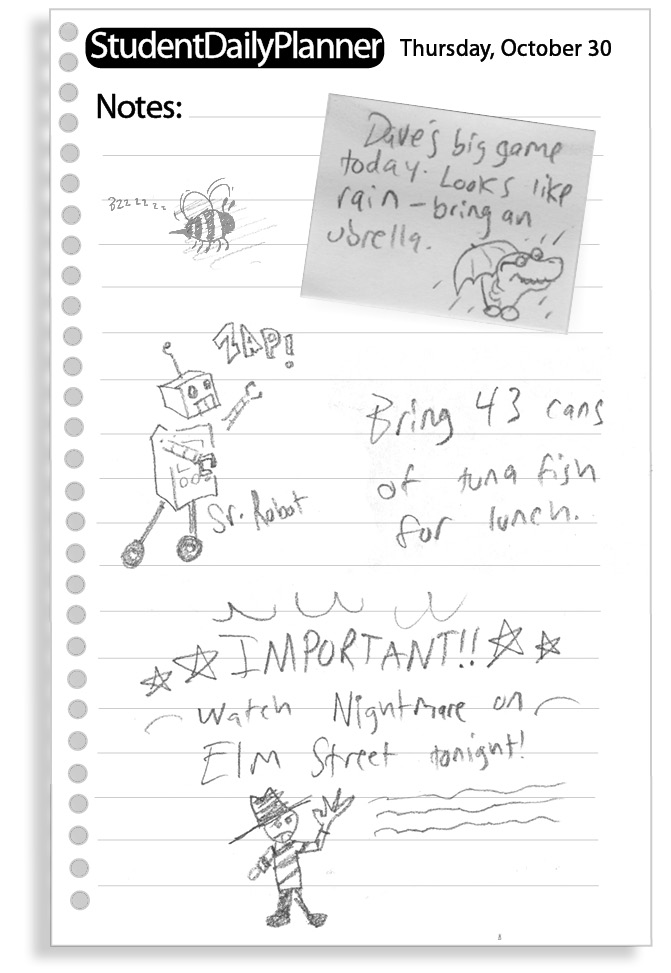

After what feels like several seconds I hear the end-of-the-day bell and suddenly awake with a start to realize that I have spent the entire day in Nurse Nancy's office. I hurry downstairs to wait for my parents to pick me up and take me to Dave's big game.

It's cold and damp outside. My favorite kind of weather. One of my fifth-grade fans comes over to me and tugs at my shirt sleeve, holding up a piece of paper for me to autograph.

“How much can you get for one of those things?” I ask. Something funny is going on in my stomach. It feels like a volcano is about to explode down there.

“A quarter,” he replies.

My price has dropped substantially since yesterday. The boy doesn't even call me “sir.” If I ever get to be a Bandito maybe my price will go up.

As I write, an overpowering urge to pass wind gets the best of me, and I release a torrent of Tums-induced flatulence into the air, accompanied by the loudest fart in the history of farting. It sounds like a hundred whoopee cushions, only louder. Mutant dinosaur burps smell like roses compared to this. The stench is overpowering. My eyes begin to water, and I feel like throwing up again.

“Oh my God, who cut the cheese?” The fifth-grader drops my autograph and staggers off, gagging. “Quick, somebody, hand me a gas mask!” he shouts. “I'm dying here.” I fan the air around me with my tail.

A streak of lightning slashes through the sky. There is a loud clap of thunder and the sky opens up. Mom's beat-up pickup truck chugs slowly toward me, huffing and puffing. It backfires loudly and comes to a stop in front of the building. “I thought you'd never get here,” I say.

“Hop in!” Dad says. He gets out of the cab and comes around to unlatch the back for me. He holds up a folded newspaper to keep the rain off his shiny bald head. “I left a tarp in there for you,” he tells me. “Better get under it. Mom's afraid you'll catch cold.”

“I'll be fine,” I say, climbing onto the truck bed. “I'm a lizard, remember? I practice thermo-regulation.”

“Hurry it up, son. The game starts in ninety minutes and we're already running late. We promised Dave we'd get there for the opening kickoff.” Dad slams the tailgate shut behind me.

“It was all my fault,” Mom calls from the driver's seat. “I got stuck behind a parade on the way to pick up your father. Who knew it was Polish Pride Day?”

“We've got to get out of here immediately, Doris,” Dad warns. He shakes the rain off himself and gets back into the cab. “There's a powerful smell of methane in the air today.”

He quickly rolls up his window, and we lurch out of the driveway. Springfield is forty miles away. They're making repairs on the main highway, so we have to take back roads. The rain is coming down in sheets. Like everything else in this old truck, the windshield wipers don't work very well. I really hope we get there on time. I know how much this game means to my brother.

After about fifteen minutes, Mom puts on the brakes and the old truck grinds to a halt in the middle of the road.

“Looks like some kind of accident up ahead,” I say, hopping out of the truck bed. “I'll go over and see what's happening.”

“Be careful, sweetie,” Mom says. “It's awfully wet out there.”

It sure is. I slide through a river of mud as I pass about a dozen stopped cars. I come to a shiny new Ford lying under a giant fallen oak. Its massive trunk and limbs block the road completely. The driver stands outside his car, shaking his head and staring sadly at the hood, which is crumpled like an accordion.

“Are you okay, mister?” I ask.

“That tree just missed me by about six inches. Hate to even think about it,” he replies. As he turns to look at me, a flash of lightning illuminates the sky, and I see a look of horror cross his face as he realizes he is talking to a creature. His eyes bulge. The blood drains from his face. “Who are you?

What

are you?”

“I'm Charlie Drinkwater, sir,” I say, holding out my claw politely. “I'm in the seventh grade at Stevenson Middle School. Pleased to meet you.” Suddenly I let loose with another stink bomb, and the man pulls out a handkerchief and covers his face. Memo to self: Don't take any more Tums. Ever.

“Get away from me, you m-m-m-m-monster!” he stammers. “Heeeelp!!!!!!!!!!”

“Anything I can do, mister?” My father approaches, holding his nose and carrying a small red plastic mug. “Cup of coffee?”

The man grabs the cup and runs to his car. He cowers behind it, covering his nose with his handkerchief.

“We called the police,” Dad says. “They say it'll take them half an hour to get here. What with the rain and the mud and all.”

“What about the game?” I ask. “Dave will be so disappointed.”

“We'll make it there by halftime, son.” Dad brushes the rain from his shoulders. “I just hope he understands.”

I make a decision. “Stand back,” I say.

“What are you going to do, son?” Dad asks.

“You'll see.” I head straight for the tree in the middle of the road.

My mom puts up her big yellow umbrella and hurries over to see what I'm doing. “Don't hurt yourself, sweetie!” she yells. She joins my dad and about twenty other drivers and passengers who have gotten out of their cars and come over to look at me and the tree.

“I'm okay, Mom, don't worry!” I yell back. I lean over, dig my claws into the tree, and attempt to drag it away from the middle of the road. My flippers sink into the soggy ground. I take a deep breath. I plant my legs firmly beneath my bulging torso and pull the tree with all my might, but I can't seem to budge it.

I let go and the tree falls back into the mud, splattering me from my flippers to the top of my head. I wipe my hooded eyelids with my claws, wrap my giant tail tightly around the tree, and hold on with all my might. I start walking slowly but surely, dragging the mighty oak with every painful step. The rain beats down on my scales. Every muscle in my body strains from the effort.

No one utters a sound until I have at last deposited the tree safely by the side of the road and collapse beside it, panting. The crowd bursts into a spontaneous round of applause, covering the sound of yet another one of my tremendous farts.

The man with the crushed Ford emerges from behind his car and walks over to us, still clutching the handkerchief to his face. “Wow. That's a very unusual kid you have there,” he tells my dad. He gingerly holds out his hand to me. I take it in my claws and shake it gently.

“We like to think so,” Dad replies, holding his nose tightly.

“He's only twelve,” my mom adds proudly. She leans over and whispers in my ear, “Get into the truck, son. Quickly. I smell a herd of cows approaching.”

Everybody heads back to their cars. Soon we are chugging down the road again. I wipe the mud from my body and try to catch my breath. The rain is letting up. I stick my head through the window. “Think we're going to make it, Dad?”

“It sure looks like it,” Dad answers, relieved.

We pick up speed, and it is smooth sailing for several minutesâuntil the truck suddenly lurches violently. The engine sputters and dies. Everything gets very quiet. We coast silently for a few more feet, land right in the middle of a giant mud puddle, and, with a sickening gurgle, sink several feet into the ooze.

I stay in the broken-down truck with Mom while Dad hitches a ride into town, rents a U-Haul van, and comes back to get us. It takes forever. We drive the rest of the way to Springfield in near silence. “It doesn't look good, does it?” I ask. Dad just stares at his watch and sighs.

WINNING ISN'T EVERYTHING

WE GET TO

the big game just as Dave completes a thirty-seven-yard pass into the end zone that breaks the tie with the Springfield Sprinters and clinches the play-offs for the Stevenson Salamanders. Ecstatic fans wearing big rubber salamander hats are screaming their heads off as we watch Dave's teammates carry him away on their shoulders, chanting, “We love Dave! We love Dave!” over and over.

My brother breaks into a huge grin when he sees us coming.

“I'm MVP, Dad! Can you believe it, guys?” Dave yells.

“That's great, son!” Dad yells back. “Congratulations!” I haven't seen Dave this happy for a long time.

When things finally calm down, Dad tells Dave that not only did we miss the opening kickoff, we were so late we missed the entire game. Dave is so disappointed he looks like he is going to cry. “All I wanted was for you guys to come and watch me play the most important game of my life,” he says. “Was that too much to ask? One lousy game?” We go back to the rented U-Haul van and wait in silence while Dave showers and changes into his regular clothes.

At last Dave gets into the van and we start the long ride home. “If you really wanted to see me play, you never should have taken that old junk heap in the first place, Mom. It's always breaking down and you know it.” Dave's voice cracks when he speaks.

“We really wanted to get to the game on time, honey, but we had to take the truck,” Mom explains. “Charlie's way too big to fit into a regular car.”

“It's all about Charlie again,” Dave says flatly.

“Don't blame me. It's not my fault,” I protest. “I didn't

ask

to be an oversized creature who can't fit into cars, Dave. You're just upset 'cause you're used being the only one in the family who gets any attention.”

“Yeah. Right,” Dave says. “Like I care. Believe me, if I wanted to be jealous of anybody, Charlie, it wouldn't be you.”

“I didn't say you were jealous of me, Dave,” I protest loudly. “That's not at all what I'm talking about. You never understand me.”

“Then why the heck don't you say what you mean!” Dave shouts.

“Children, stop it this minute,” Dad orders sternly. “Charlie, don't be so argumentative. Dave, don't yell at your little brother. It's not nice.”

After several minutes, Mom breaks the silence. “If we didn't take the truck tonight we would have had to leave Charlie at home. And I know you wouldn't have wanted that, Dave.”

“Would that have been so terrible?” Dave asks. “Charlie doesn't even

like

football. He doesn't know the first thing about it. He could have stayed home and written another one of his A papers like he always does. He wouldn't have cared. Why does everybody worry about

Charlie

all the time? Why doesn't anybody ever worry about me for a change?”

“I

do

worry about you, Dave,” I tell my brother. “And no matter what you say, we really tried to get to your game on time, and I'm totally sorry we didn't make it.”

“Apology not accepted,” Dave grumbles.

“Don't be so stubborn, honey,” Mom says. “We all worry about you, Dave.”

“We're proud of you, son,” Dad says quietly. “We know you worked like a dog to win that award tonight. And we wish we could have witnessed your great success. But it wasn't your mom's fault we didn't get there. And don't blame Charlie, either. This afternoon your little brother carried a giant oak tree all the way across a rain-soaked street so that we could get to that game on time. I just want you to know that.”

“I don't care. I still feel terrible.” Dave's voice drifts off and he stares out the window. “I want to crawl into bed and pretend tonight never happened.”

Just because your big brother is older than you, it doesn't always mean he's more grown up.

Balthazar is the only one who seems the least bit interested in food tonight. He barks happily when he hears everyone coming and sniffs for signs of hidden surprises in our pockets as we hang up our rain-soaked coats. He doesn't seem afraid of me anymore. I'd say “wary” is more like it. It's not much. But it's an improvement.

“Aren't you going to Janie's house, Dave?” Mom asks. “I thought she was having everybody over for the after-party.”

“She is,” Dave replies. “I told her I had to go home and soak my wrist.”

“Did you hurt yourself again?” I ask.

“No,” he replies tersely. “I don't exactly feel like celebrating tonight.”

When we get up to our room Dave puts his MVP trophy on his bookshelf next to his eight million other trophies and then gets ready for bed. I pull my crate over to my desk and start doing my math assignment: “Car X and Car Y leave Chicago at exactly the same time. Car X travels at an average speed of forty-two miles per hour. Car Y travels . . .” I hear the click of Balthazar's nails in the hallway. I look up and see him hovering in the doorway, watching me cautiously.

“Hey, Bally. What's up?” I ask. He whines softly. “Don't be afraid, boy.” I crane my long, skinny neck over and lean my head way down so I am eye to eye with him. “Want a treat?” His ears perk up, and I can tell he is listening to me really hard. A glimmer of recognition crosses his big brown eyes. He barks softly and wags his tail. I think he has just figured out who I am.

“It's me. Charlie,” I whisper. “It's really me.” I take the liver snap out of my pocket. I have been carrying it around with me all week, waiting for just the right moment to give it to him. I hold it out in my claws. He cocks his head to one side and stares at me.

“Take it. Go on. I won't hurt you, Bally. I want us to be friends again.” He walks slowly over to the bed and takes the liver snap from my claw in his lips. “Good Bally.” His tail thumps loudly on the floor. “I've really missed you, pal.”

“Who are you talking to?” Dave asks me as he comes out of the bathroom and gets into bed.

“Nobody.”

“Oh. For a second I thought you were talking to me.”

“I wasn't.”

“That's good,” Dave says. “Because I don't much feel like talking to anybody tonight.” He switches off the light beside his bed, punches his pillow a couple of times, and then tosses and turns. I listen to the whistle of a far-away train. In a few minutes I can hear my brother softly snoring.

I look over at Balthazar. He hasn't taken his eyes off me. He waits near the head of my bed and tentatively holds out his paw. I reach out slowly and take it in my claw. I don't want to frighten him. “Come up here with me, Bally,” I whisper. “C'mon. You can do it. Up, boy.” I pat the covers next to me. “Up.”

For a few long moments Balthazar looks at me like he is trying to make up his mind, and then he leaps onto my bed, turns around twice, and snuggles up right next to me. “Good boy.” He has, it appears, made peace with my transformation at last. I'm glad to know that at least somebody has.