Creation (33 page)

Authors: Katherine Govier

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #FIC000000, #FIC019000, #FIC014000, #FIC041000

“Not fully an artist, not fully a woman. Is that my fate?”

He locked his hands at the small of her back and pulled her into his chest until neither of them could breathe.

“No, Maria. It is not to be your fate.”

“But what, then?”

To his mind came Jeanne Rabin, the young beauty who could neither read nor write, the graceful fiery girl who bore him and died, his father’s mistress. He did not repudiate her, but celebrated her. “You can be as you are, a help and a comfort to me.” He had nothing else to say. He lifted his empty hands. It meant

I want you

.

Suddenly Maria was three feet away. “You fail in your imagination, Mr. Audubon.”

His arms circled empty air. “How do I fail, Maria?”

“‘Drawn from Nature, by J. J. Audubon.’ You write it on every watercolour. But you do not draw the birds from nature. You watch them, it is true. You adore them in nature. But they are not good enough for you that way. You have to kill them. Your birds suffer to give you your art. You don’t allow them life.”

“They do not suffer, Maria. To suffer is to have hope. Birds do not hope.”

“Is that your final word?”

He did not understand what they were talking about.

Maria collected her brushes and colours. She took up the paper between two fingers. There was half a butterfly on it.

“Can you imagine that I would be content with this?” she taunted.

Then she was gone, so slender, so quick amongst the tropical plants. She paced toward the house alongside the peacocks that strutted in their alley. He came along behind her.

“You — and my brother-in-law. There are two of you,” she said. “Old men.” She had changed again. It was her teasing voice. “You fight over my kisses. For you it is an amusement. You must know this. I’ll have one man for a husband, not two to court me. I will be an artist of the world, not of the garden.”

“

Maria set down her brush. Her drawing

fluttered off her lap; the butterfly rose in alarm and was gone

.”

J

ohnny pulls his father from the cramped hold. Audubon protests.

“I’m working.”

“You’ll work better once you’ve seen this.”

Johnny yanks the thigh-high moccasins onto his father’s feet. Audubon blinks in the unaccustomed light. There is so much sky and water, one can be blinded simply by the emptiness.

They go to the cliffs where they have seen the razorbills light, and poke sticks into the holes between the rocks. Some of these cracks or fissures are as tall as a man but not wide enough to slide into sideways. Others are the size of a fist but deeper than the sticks can probe. They find one they can crawl into. It is for this kind of adventure that the father brought the son to Labrador. Johnny is too wild, Lucy said; you must harness that energy. But now it’s different — Johnny is bringing his father along.

As they make their way on hands and knees into the smooth-washed rock, birds begin to cry. Audubon would like to cover his ears but he cannot: he is using his hands for feet. The cries intensify as he crawls deeper, they echo and return; it is as if he is crawling down the throat of a bird. There is also the thrum of beating wings from farther down the wet tunnel. He makes himself as small as possible, pushing his ten-foot pole ahead of him. Birds begin to fly by his ears, trying to escape. Their panicked wings brush his face. They bash themselves into the rocky sides of the cavern. They fall and in the dark he kneels on them, squashes them under the heel of his hands. Hundreds of birds rush past him toward the air. They are crying.

“I can go no farther,” he whispers to his son.

Johnny is behind. He does not hear.

“I can go no farther, son!”

“Are you tired?”

“No! I cannot breathe. You go on.”

But Johnny would have to crawl over his father’s body to continue.

The two begin to crawl backward, still in the cloud of birds. Ahead is the laughter of the others as they scare up and spear the panicked birds. Audubon’s heart beats high in his chest. Over Johnny’s back he can see a bullethole of light: the opening. A dab of sky on the slick blackness. When he has gone perhaps ten more feet he looks again. The dab is slightly larger. In this way, with the crying of birds in his ears and wingtips brushing his cheeks, he gets himself out. Johnny crawls back into the crevice.

Air! Audubon crawls to the ledge, his chest heaving. He lies for a moment looking skyward, and then turns to see what they have wrought. Dazed with fear, and making their pitiful sounds, the little auks fly directly into the muskets of the sailors, who have stationed themselves just beyond the mouth of the cave and are shooting for the fun of it.

As the birds scatter and fall his heart pounds and his breath comes short with their panic. He changes places then, on that cliffside, with the birds. He imagines himself the prey and the men his pursuers.

He has done this since he was a boy. He has feared the guns, the volley of shots, the shouting, the running.

When he was nine he stood at the high windows of his father’s house in Nantes. The soldiers of the Commune pointed their muskets at people in the streets and fired. The explosions ricocheted off the grey stone walls and people fled in panic. He stayed in the window and saw, through the smoke, the lucky ones escaping, running uphill.

And before that, in Santo Domingo, he ran from guns, only hip high to the dark women with their flowered skirts who dragged him through the narrow rows of sugar cane. Behind him were brandished torches, shouts, and blood-chilling screams.

But he is a man now, and no soldiers, no overseers, pursue him. He has his gun. He is furthest from being the victim when he has his gun.

He lies a minute, feeling strange, and faint. Then he kicks himself to his feet and takes up his musket. Soon they have a pile of birds on the rocks.

O

N THE SHORE

by the anchorage, the cook and the boy pluck the birds’ feathers. Johnny has a basket of eggs. Each one is pure white, with one end dotted with blackish red spots.

“Deep in the crevice we found many eggs lying close together, deposited on heaps of stones. Do you see how clever the birds are? In this way, when the water rushes down the cavern, it flows beneath them through the rocks, and so the eggs are not ruined,” says Johnny.

“How many eggs in a group?” asks Audubon.

“We know each lays only one egg and yet, deep in the crack, we found two under almost every bird.”

“Because the place is more secure?” says Audubon. “Or less?”

He reaches down again to Johnny’s sack and takes out a young live auk. It is tiny, its bill showing nothing of the huge thick curve which it will take on in adulthood. The chick is soft and downy. It looks blindly into his eyes and chirps, air whistling faintly through its bill. He offers his finger. The little bird snaps at it, taking it between the top and bottom of its bill as if it were a shrimp. He tries to remove his finger from the bill of the chick, but he cannot. He stands and lets the little bird dangle from his finger by its own strength.

He shakes his hand but the chick does not drop off. He puts his fingers around its little throat and presses. Still the bill does not open.

It would rather choke than let go.

R

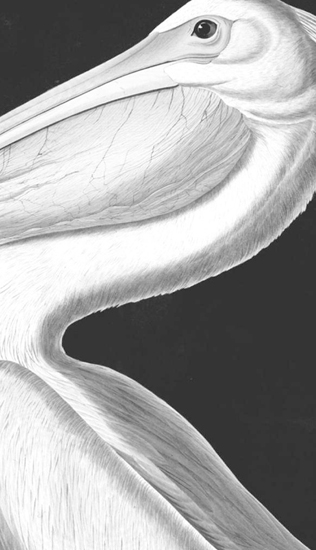

obert Havell lifts the watercolour of the White Pelican out of its wooden packing box. Audubon has outdone himself. The work gets better and better.

The White Pelican is defiant against the night sky. Behind it, a canopy of trees closes over the inlet. The pelican’s big muscular body exudes strength and pride and a kind of amoral energy. It dares the onlooker to be its equal.

And Havell finally realizes that for Audubon the pelican, the bird, is not the subject of the painting. The subject is a state of being. Wild. The pelican is a creature of it, inviolate. He is crude, custodial. He is standing in the present. The future is to the left of the page, where his eyes are fixed. Statuesque, even comical in his particularity, he neither bends to it nor retreats, but challenges it to envelop him.

And when it does, the bird will rise on those contraptions he calls wings and flap awkwardly away.

Havell has never seen a White Pelican, or an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, or indeed most of the birds he engraves. They live across the Atlantic, in a land he knows only from letters, a land created as backdrop to birds, as far as he can tell.

He has never been to Labrador, or to Florida, where Audubon saw this bird, or to Charleston, where he completed this painting in the home of his friend John Bachman, aided by Lucy, Johnny, and the mysterious Maria Martin. Robert Havell spends all his days in his shop at 77 Oxford Street in grimy London. He has remained there since he began this work, which has become his life.

This has not stopped him from creating landscapes for the birds found by his employer in America. He has engraved meandering swamps, threatening thunderclouds, crescent waterfalls, ice-bound rocks and even the tiny rims of city dwellings. Audubon not only allows this but increasingly has come to rely on it as he races to finish his enormous book. Havell adds flowers and insects where these have not already been added by others. He sets stages for the birds, which, to him, are actors; he creates his own landscapes.

London is grey and ugly and dead. Increasingly Havell finds the city to be a vacancy, in contrast to the wild creatures in their dense wooded hideouts, in their mad costumes of coloured feathers. The vision of a bombastic stranger, as alternately harsh and affectionate as his father was, and not so much older than himself, has taken over his world.

Today he will engrave the plate of the White Pelican.

E

ARLIER IN THE MORNING

he sent two boys to the coppersmith’s in Shoe Lane, Holborn. They carried the plate back along the streets, between them; at thirty inches by forty inches, it is awkward and heavy. The boys then heated it over the fire, and when it was so hot that they needed gloves to touch it, they took it out of the fire and laid it on a table, where they rubbed the polished side of it with etching wax. They warmed the plate again to make the wax flow, took it off the fire again, and dabbed it all over with the dabber. Then they suspended the plate from the ceiling by four chains, one in each corner. Now, hung overhead this way, it is ready for him.

He positions himself underneath. He takes four wax tapers tied together, lights them and holds them over his head. Standing directly beneath the plate, he looks up. His tail of hair, tied at the nape of his neck, hangs down his back. He positions himself with one foot forward and one back, and one fist pressed into the base of his spine to lessen the back pain. Looking up, he begins to heat the plate, moving his torch hand back and forth so the flame blackens the wax that will be the etching ground. He never lets the flame stand still, as it would burn the wax.

When the plate is blackened, he steps away to let it grow cold, at which point it will be ready to receive the bird.

The White Pelican waits. He fills the huge page with his deep chest and a profile that strains credibility. The White Pelican is not white at all but brilliant yellow. The big yellow sac under his bill and his fierce eye are balanced, at rear, by a ducktail of soft yellow. Havell does not fail to register that this bird was painted after Audubon met Maria Martin. The artist has become more dramatic, more confident. He has been aware of the difference for some time now. In the past year Audubon’s birds have ceased to be illustrations. With the pelican, the artist has managed to give the scientific information he prides himself on giving in a backhanded way; he’s not looking at, but inside, this big bird. The picture is bird

qua

bird.

H

AVELL WILL MAKE

a new background for the pelican. He has the entry for the letter press, which Audubon has written: “Ranged along the margins of a sand-bar, in broken array, stand a hundred heavy-bodied Pelicans,” he reads. These are the artist’s words, or perhaps the artist’s words as Lucy has rewritten them, Lucy herself never having seen the birds. “The Pelicans drive the little fishes toward the shallow shore, and then, with their enormous pouches spread like so many bag-nets, scoop them out and devour them in thousands.”