Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors (52 page)

Read Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #Nightmare

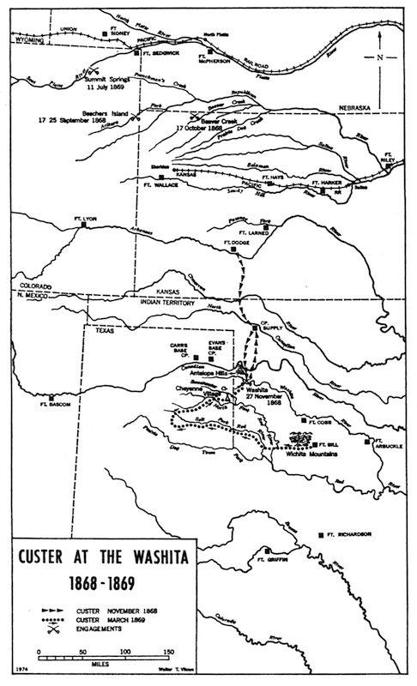

After establishing Camp Supply, Sheridan had to mediate a dispute over rank. The governor of Kansas had raised a force of volunteers for the Indian wars and was bringing it, under his own command, to Camp Supply. Fearful that the governor would claim seniority, Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Sully of the Army’s expedition issued an order claiming the command in his capacity as a brevet brigadier general. Lieutenant Colonel Custer promptly countered with an order assuming command in his brevet grade of major general. Sheridan confirmed Custer and sent Sully back to district headquarters at Fort Leavenworth.

18

Custer prepared to march the next day, before the Kansas volunteers arrived.

On the morning of November 23, 1868, Custer woke to find his tent covered with snow. A foot of fresh snow was already on the ground and the wind was howling, bringing more snow with it. Vision

was limited to a couple of yards. “How will this do for a winter campaign?” Adjutant Cooke asked Custer as he delivered the morning report. “Just what we want,” was the reply. Custer rode over to Sheridan’s tent to say good-bye. Sheridan asked him about the storm. “Just what we want,” Custer repeated. “If this stays on the ground a week, I promise to return with the report of a battle with the Indians.”

19

The snow was, in truth, a Godsend, for as every hunter knows, tracking game in a fresh snow is child’s play—if the hunter is strong enough to keep going—while tracking game for any distance over the bare prairie is almost impossible.

Surrounded by his dogs, Custer had “Boots and Saddles” blown, swung onto his horse, and signaled to the military band that he was bringing along. To the tune of “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” the column moved out.

20

The storm was a challenge to which Custer responded magnificently. Setting his course south by a compass (not even the Osage guides could find their way in the blinding snow) he rode at the head of the column. He kept the men close up, in constant physical touch with each other, so none got lost. Somehow he managed to make fifteen miles that day. He led the men to Wolf Creek, where they dug in the snowdrifts to find fallen trees. When the fires were built and the coffee boiling, the men congratulated each other on how well they had done. Their morale was high. Custer made a bed for himself with a buffalo robe, lay down with a huge dog on each side of him to provide warmth, and slept soundly.

21

Over the next few days the eight hundred cavalrymen moved steadily south, hoping to strike the fresh trail of an Indian war party returning to its winter camp. Custer caught a buffalo bull floundering in a snow-filled draw and killed it; other soldiers brought down more buffalo and the men enjoyed fresh meat. The nights were bitterly cold, but now that the storm had passed the days were sunny and warmer, so the men’s spirits remained high.

On November 26 Custer struck the trail he had been hoping for. Tracks indicated that it was a party of Indians returning from Kansas to their village in Oklahoma. Custer had no idea what the Indians might have been doing in Kansas, what tribe they belonged to, their strength, or their location—indeed, all he knew was that his column was somewhere south of the North Canadian River. But the fresh tracks of the prey are like a magnet to the hunter, and he followed them south through the day and into the night. He cut loose from his wagon train in order to speed up his movement, leaving eighty men to guard it, with instructions to follow his trail.

After darkness fell, Custer joined the Osage guides at the head of the column. The melting snow was freezing again, so the horses made a racket as they broke through the frozen crust. Custer had the men keep a half mile behind the guides in order to minimize the noise. He stopped once to feed the horses some oats and allowed the men to make some coffee to go with their hardtack. It was the only meal the animals or troopers had eaten since 4

A.M.,

and they would not eat again until noon the next day. That the soldiers could keep going under such conditions was a tribute to Custer’s ability as a trainer and leader of men.

22

When he took up the chase again, Custer passed along orders that no one was to speak above a whisper and that no pipes or cigars could be lit. Silently, except for the crunch of broken snow, his 720 men rode mile after mile. Around midnight, one of the Osage guides smelled smoke. Custer couldn’t smell any and wondered if the guide was losing his nerve—Indians did not like to fight at night, he knew, and the Osage guides were fearful of bumping into a big village. Custer sent the other guides forward to investigate while the column followed at a slow walk.

After an hour or so, one of the guides came creeping back to Custer. “What is it?” Custer asked. In his broken English, the Osage replied, “Heaps Injuns down there.”

Custer dismounted and crawled forward through the snow to the crest of the hill. Looking down into a valley (he had not known he was near a river) he saw what looked like, in the uncertain light, a large body of animals half a mile away. His first thought was that they were buffalo. Turning to the guide, he asked in a low tone why the Osage thought they were Indian ponies. “Me heard dog bark,” was the reply. Still not fully convinced, Custer strained to hear something, anything. He thought he heard a bell, which might mean a pony herd, as the Indians sometimes put a bell on the lead mare. Still uncertain, he hesitated—and then heard the sound that convinced him that he had finally run the prey to earth. A baby cried out in the night.

23

Quietly returning to his officers, Custer blurted out orders in staccato sentences. He divided his column into four nearly equal detachments. One group would swing around to the far end of the village, while two others would proceed to the sides. Custer would stay with the fourth detachment at his present location. Once they had the village surrounded, they would stay in place until first light, when Custer would give the signal to attack.

Here was audacity indeed. Here was the pay-off for Sherman and

Sheridan in rescuing Custer from disgrace. He was doing exactly what they had hoped he would do. Custer had no idea in the world how many Indians were below him, who they were, or where he was. His men and horses were exhausted. It was freezing cold, but he ordered his men to stand silently, not even allowing them to stamp their feet, for fear the Indians would discover their presence. He was going to attack at dawn from four directions at once. He had made no reconnaissance, held nothing back in reserve, was miles away from his wagon train, and had ordered the most complex maneuver in military affairs, a four-pronged simultaneous attack. It was foolish at best, crazy at worst, but it was also magnificent and it was pure Custer.

This would be Custer’s first big fight with Indians and he intended to make the most of it. After catching an hour’s cat nap on a buffalo robe on the snow, he walked around among the men, building up their confidence. When the sky began to brighten he had them remove their overcoats and haversacks so they would be able to fight unencumbered.

At the first full light Custer had the band strike up the regiment’s favorite tune, “Garry Owen.” The music didn’t last long, as saliva froze in the instruments, but it hardly mattered, because with a whoop, Custer led his column on a charge down into the village, shooting through the tipis. The other columns were all in place and they attacked, too, firing as fast as they could.

Warriors rushed from their tipis, confused, disorganized, unbelieving. Custer’s men shot them down. Some Indians managed to get their weapons and fled to the safety of the Washita River, where they stood in waist-deep, freezing water, behind the protecting bank of the river, and started returning the fire. Others managed to get into some nearby timber and began to fight. But that first assault was overwhelming, and Custer had control of the village. His men were shooting anything that moved. Many of the troopers had been fruitlessly chasing Indians for two years and they poured out their frustrations; everyone was extremely tense after the nightlong approach to the village and the indiscriminate killing relieved the tension. In any event, the soldiers said later, it was hard to tell warriors from squaws, especially because a few of the squaws had taken up weapons and were fighting back. So were Indian boys of ten years of age. The troopers shot them all down. Still, according to George Grinnell, who got his information from the Indians, “practically all the women and children who were killed were shot while hiding in the brush or trying to run away through it.”

24

Within an hour, probably less, resistance was minimal. A few warriors kept up a sporadic firing from the banks of the river, but for all practical purposes the battle was over. Looking around, Custer could see dead Indians everywhere, one hundred or more of them, their blood bright on the snow. He was in possession of fifty-one lodges and a herd of nearly nine hundred ponies.

25

Custer had won a smashing victory. Best of all, inside the tipis his men found fragments of letters, bits of bedding from Kansas homesteads, daguerreotypes, and other pieces of evidence that these Indians had indeed been guilty of raiding into Kansas. The Indians had held two white captives, too, whom they had killed when the troops overran the village. Now no one could accuse Custer of attacking innocent Indians, of being like Chivington at Sand Creek. And it had all been accomplished with small loss; one officer killed and two officers and eleven enlisted men wounded. Major Elliott and a nineteen-man detachment were missing, but someone had seen Elliott and the men giving chase to a few Indians who were attempting to escape and he was expected back shortly.

While his men reduced the few remaining pockets of resistance, Custer set up a field hospital in the largest tipi and wondered what to do with his victory. He also began to wonder whom he had beaten. Fifty-three women and children had remained hidden inside their lodges when the attack began; they were now all prisoners. Through his interpreter, Custer learned that he had just rubbed out Black Kettle’s Cheyennes—the same Cheyennes who had been struck at Sand Creek. Black Kettle himself, always a champion of peace, had been one of the first to die.

26

Custer also learned that he was at the far end of an enormous Indian winter camp; downstream were the villages of the Kiowas, Arapahoes, Apaches, Comanches, and others.

27

Custer had a long talk with Black Kettle’s sister. She said she had told Black Kettle what would happen if he didn’t curb the young braves, on whom she blamed everything. She went on and on in that vein, until Custer began to suspect that she was playing for time. Growing impatient, he was about to cut her off when she placed the hand of a beautiful seventeen-year-old Cheyenne girl in his. “What is this woman doing?” Custer asked his interpreter.

“Why, she is marrying you to that young squaw,” was the reply. Custer dropped her hand and hurried outside. There he saw an ammunition wagon rattle into the village; the quartermaster of the wagon train had sent it on ahead.

28

By noon warriors from the downstream villages began to appear

on the bluffs surrounding Custer’s position. As their numbers increased they began firing into Custer’s ranks. He formed a defensive perimeter and decided that the best thing, all in all, was to get the hell out of there and report his victory to Sheridan. “On all sides of us the Indians could now be seen in considerable numbers,” he later wrote, “so that from being the surrounding party, as we had been in the morning, we now found ourselves surrounded and occupying the position of defenders of the village.” He gave the impression that the Indians were present in overwhelming numbers, but as a close student of the battle, Milo Quaife, convincingly demonstrates, there could not have been more than 1,500 warriors at the outside, and more likely less than one thousand that he had to deal with.

29

’ This was hardly a force able to stand up to some seven hundred well-mounted and well-armed cavalrymen.

Nevertheless, Custer decided to retreat. First he followed Hancock’s example and burned the village, destroying more than one thousand buffalo robes, seven hundred pounds of tobacco, enormous quantities of meat, and other material. Lieutenant E. S. Godfrey later remembered tossing a beautifully beaded buckskin gown decorated with elks’ teeth into the flames.

30

While the fires roared, Custer thought about what to do with the captured pony herd. The pintos were afraid of white men and could not be controlled by them; if Custer tried to move out with nine hundred ponies he would never be able to move with any speed, and besides, if he kept the animals, the Indians would attack ceaselessly in an effort to get them back. Dismayed at the alternatives—he loved horses as much as any man—he sadly told the captive women and children to select ponies for themselves, so that they could ride back to Camp Supply with the column. After the captives made their choices, Custer detailed four of his ten companies of cavalry and ordered the men to shoot the ponies. Within minutes more than eight hundred pintos lay on the ground, neighing, kicking, in their death throes, the blood spurting from their wounds, making the snow-covered ground more red than white.

31