Cracked (6 page)

Authors: James Davies

“Will this do damage to the credibility of psychiatry itself?”

“Well, James, I think things have been unfortunate in that regard,” said Frances pensively, “because that's already happened.”

For one reason or another, it just felt appropriate to end our interview there.

6

The criticisms Frances expressed to me regarding

DSM-5

have now infected the wider mental health community. During 2012 a flurry of damning editorials, including two eloquent pieces in

Lancet

and one in the

New England Journal of Medicine,

strongly

criticized

the

DSM-5

's pathologization of grief. This chorus of dissent has been repeated in over one hundred critical articles in the world press and by the appeal of over one hundred thousand grievers worldwide. Furthermore, in 2012 an online petition went live protesting against the changes proposed by the

DSM-5

. It was endorsed by over fifty organizations related to the mental health industry, including the British Psychological Society, the Danish Psychological Society, and the American Counseling Association.

The arguments they advanced were similar to those made by Allen Frances: By lowering the diagnostic thresholds for warranting a diagnosis, more people may be unnecessarily branded mentally unwell; by including many new disorders that appear to lack scientific justification, there will be more inappropriate medical treatment of vulnerable populations (children, veterans, the infirm, and the elderly); by deemphasizing the sociocultural causes of suffering, biological causes will continue to be wrongly privileged. In short, the petition then concludes, “In light of the growing empirical evidence that neurobiology does not fully account for the emergence of mental distress, as well as new longitudinal studies revealing long-term hazards of psychotropic treatment, we believe that these changes pose substantial risks to patients/clients, practitioners, and the mental health profession in general.”

37

With all this mounting pressure on the

DSM

to seriously mend its ways, who better to ask than the chair of

DSM-5

whether these criticisms will have any impact. So I tried to get the interview, but unfortunately I was unsuccessful. This is because, as I would learn, all members of the

DSM-5

taskforce have actually been forced to sign confidentiality agreements by the APA, which makes their talking frankly about what they are doing legally precarious. So instead, I put the question to the next best person, Dr. Robert Spitzer. Did Spitzer think the

DSM-5

should stop and reconsider before going through with publication?

“Well, they have already had to postpone publication several times,” said Spitzer candidly, “because of all the problems. So I just think the

DSM

committee should ask the APA for an extension until all the work has been done properly. But this is not happening, and I think it is because the APA wants it published next yearâit needs the huge amount of money sales will bring.”

Indeed, the APA has spent around $25 million developing

DSM-5

and now needs to recoup its investment, as the coffers at the APA are now low. As it needs the $5 million a year the

DSM

makes from its global sales, the APA is now in a real dilemma, as Allen Frances pointed out: “Will it put public trust first and delay publication of

DSM-5

until it can be done right? Or will it protect profits first and prematurely rush a second- or third-rate product into print?”

The answer came on December 1, 2012, when on that fateful day, and only having minimally addressed a handful of criticisms, the APA finally approved the new

DSM-5

for global publication. As the chair of

DSM-5

, David J. Kupfer, joyously put it: “I'm thrilled to have the Board of Trustees' support for the revisions and for us to move forward toward the publication.” What this approval means is that by the time you have this book in hand, on a shelf somewhere very near you now sits the manual that will influence mental health practice for decades to come.

As to what further damage all this will do, of course, remains to be seen. But if the legions of authoritative critics are to be believed, then the future does not look so bright. We can expect the inflation of diagnosed schoolchildren like those in Canada, and vastly more medicated youths like young Dominic in London. In short, we can expect vaulting numbers of children and adults alike to become yet more statistical droplets in the ever-expanding pool of the mentally unwell.

THE DEPRESSING TRUTH ABOUT HAPPY PILLS

W

hen I started out working as a psychotherapist in the NHS in the UK, I knew nothing about the construction of mental disorders, about false psychiatric epidemics, about the out-of-control medicalization of normality, about the disconcerting confessions of

DSM

chairmen, and certainly nothing about the alarming facts that I'm about to reveal to you now.

Like most people inside and outside the medical community, I used to think that antidepressants worked. I pretty much accepted, like everyone else, that these pills modified chemical levels in the brain in order to create improved states of mind. This was why most of the patients referred to me for long-term psychotherapy were taking antidepressant medication. The pills helped stabilize their moods to the point that they could engage more successfully in therapeutic work. That is what I was taught. That was the party line. But it wasn't long before I discovered the party line is wrong.

But how could this be? The pharmaceutical industry makes over $20 billion each year from antidepressant medications. Doctors up and down the country are convinced of their effectiveness. The media regularly and glowingly reports how these pills help millions each year. And countless patients claim that their lives would have been ruined without them. Surely it would therefore be simply conspiratorial to suggest that all this money and all this enthusiasm is the product of a misleading myth.

That is precisely what I am about to suggest, as solid scientific research now shows clearly that antidepressants don't actually work, or at least not in the way people think.

2

In early May 2011, I wrote to Professor Irving Kirsch, an associate director at Harvard Medical School and today perhaps the most talked about figure internationally in antidepressant research. Our exchange went something like this:

38

Dear Professor Kirsch,

I am writing a book on psychiatry and I'd appreciate the opportunity to interview you about your important work on antidepressants. I'll be in Boston in early May. If it's convenient, I would love to come over to Harvard and interview you there. Just say the word.

Dear Dr. Davies,

I'd be delighted to chat with you, but I'm not in Boston in early May. I am now in Florence, but I'll be at my home in the UK in April. Perhaps we can meet there?

Dear Professor Kirsch,

In the UK? Perfect. Where shall I meet you?

Dear Dr. Davies,

At my home in Scorborough, Yorkshire ⦠you know that part of the world?

Dear Professor Kirsch,

Sure, I know it well â¦

⦠But what, I was then tempted to ask, is a Harvard professor doing living on the Yorkshire moors?

One Friday morning in April, I would find out. I set off from my home in Shepherds Bush, West London, and drove 250 miles up the M1 to rural Scorborough. Kirsch, it turns out, had been a professor at the University of Hull before moving to Harvard Medical School. When working at Hull, Kirsch and his wife had become so attached to the surrounding area that they had decided to keep paying the rent on their lovely Georgian villa, which was sequestered in an urbane and picturesque little hamlet just outside the city.

As my exhausted little car rattled up onto the driveway, Kirsch was standing by the door. He waved and smiled kindly, greeting me like a friend he hadn't seen for years. After entering the house, he kept turning around eagerly to ask me questions as he led me down a long corridor and into his main drawing room.

It was grand and congenial, like an Oxbridge senior common room, festooned with authentic Georgian furnishings and illuminated with the light from a flickering chandelier and a sweeping bay window. We settled onto two plump easy chairs in front of the old fireplace whose chimney breast, which made me smile as I noticed, was stuffed with newspaper to ward off the bitter Yorkshire wind.

As I surveyed the man and the scene, it was clear to me that Kirsch had traveled great distances in his lifeâsocially, artistically, geographically, and intellectually. He was a real, live product of the American Dream. He was born to Polish immigrants in New York City in 1943. He'd been heavily involved in the civil rights movements of the 1960s, while also writing pamphlets against the Vietnam War (at the request of Bertrand Russell). Before becoming a psychologist in his early thirties, he'd worked as a violinist, accompanying artists like Aretha Franklin and enjoying a stint in the Toledo Symphony Orchestra. Just before gaining his PhD in psychology in 1975, he was nominated for a Grammy award for an album he'd produced, which included doctored snippets from the Watergate hearings.

39

His journey is, therefore, an interesting one: his life has oscillated between music, psychology, pacifism, and politicsâbetween New York, California, Krakow, Boston, and now Scorborough.

It seemed ironic to start our interview by asking Kirsch, a devoted pacifist in his youth, about a war he had recently started within the medical community ignited by his scientific research. The war was so turbulent because so much was at stake, not only for the millions of adults and children who now take antidepressants, or for the hundreds of thousands of doctors around the globe who are now prescribing them, but also for the pharmaceutical industry that makes billions a year from antidepressant sales. What I wanted to know from Kirsch was how someone so seemingly peaceful could have created such widespread pandemonium.

“By complete accident,” answered Kirsch with a boyish smile as he sipped tea from an antique china cup. “I wasn't really interested in antidepressants when I started out as a psychologist. I was more taken by the power of beliefâhow our expectations can shape who we are, how we feel, and, more specifically, whether or not we recover from illness. Like everyone else at the time,” continued Kirsch, “I just assumed antidepressants worked because of their chemical ingredients. That's why I'd occasionally referred depressed patients to psychiatrists for antidepressant medication.”

Everything would change for Kirsch after a young man called Guy Sapirstein approached him in the mid-1990s. This bright and eager graduate student had become fascinated in the placebo effects of antidepressants. What gripped Sapirstein was how depressed patients could actually feel better by taking a sugar pill if they

believed

it to be an antidepressant. This led Sapirstein to wonder about the extent to which antidepressants worked through the placebo effect, by creating in patients an expectation of healing so strong that their symptoms actually disappeared.

Once Sapirstein had outlined his interests, Kirsch knew he wanted to get on board. And so it wasn't long before both men set about investigating the question together: To what extent did antidepressants work because of their placebo effects?

“Instead of doing a brand-new study ,”said Kirsch, describing the method they employed, “we decided to do what is called a meta-analysis. This worked by gathering all the studies we could find that had compared the effects of antidepressants to the effects of placebos on depressed patients. We then pooled all the results to get an overall figure.”

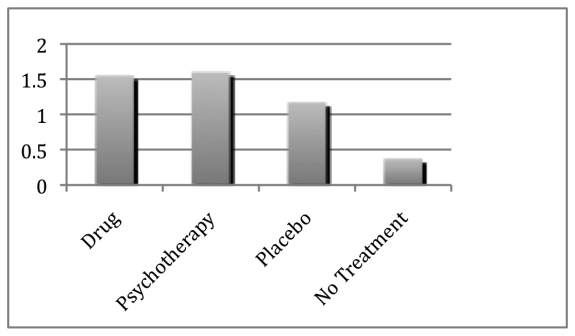

In total, Kirsch's meta-analysis covered thirty-eight clinical trials, the results of which, when taken en masse, led to a startling conclusion. “What we expected to find,” said Kirsch, lowering his teacup, “was that people who took the antidepressant would do far better than those taking the placebo, the sugar pill. We couldn't have been more wrong.” And if you look at the graph below you'll see exactly what Kirsch means:

40

The first thing you'll notice is that

all

the groups actually get better on the scale of improvement, even those who had received no treatment at all. This is because many incidences of depression spontaneously reduce by themselves after time without being actively treated. You'll also see that both psychotherapy and drug groups get significantly better. But, oddly, so does the placebo group. More bizarre still, the difference in improvement between placebo and antidepressant groups is only about 0.4 points, which was a strikingly small amount.

“This result genuinely surprised us,” said Kirsch, leaning forward intently, “because the difference between placebos and antidepressants was far smaller than anything we had read about or anticipated.” In fact, Kirsch and Sapirstein were so taken aback by these findings that they initially doubted the integrity of their research. “We felt we must have done something wrong in either collecting or analyzing the data,” confessed Kirsch, “but what? We just couldn't figure it out.”

So in the following months Kirsch and Sapirstein analyzed and reanalyzed their data. They cut the figures this way and that, counted the statistics differently, checked what pills were assessed in each trial, and reexamined their findings with colleagues. But each time, the same results came out. Either they could not spot the mistake, or there simply was no mistake to spot. Eventually there seemed to be no other alternative than to take the risk and publish their findings that antidepressants, according to their data, appeared to be only moderately more effective than sugar pills.

“Once our paper appeared,” Kirsch recalled, smiling, “there was ⦠well, how can I put it ⦠controversy. The most significant critique was that we had left out many important trials from our meta-analysis. Perhaps an analysis that included those studies would lead to a different conclusion.”

Indeed, Thomas Moore, a professor at George Washington University, pointed this out to Kirsch by revealing that his meta-analysis had only assessed the

published

trials on whether antidepressants work. Their study had therefore failed to include the drug trials left

unpublished

by the pharmaceutical companies who conducted them. Kirsch and Sapirstein had been unaware that pharmaceutical companies regularly withhold trials from publication. When Kirsch looked into how many trials this amounted to, he was aghast at what he found: nearly 40 percent of all the trials on antidepressant drugs had not been publishedâa staggering amount by all accounts.

I asked Kirsch what he did next. “Moore suggested we appeal through the Freedom of Information Act to get the unpublished company studies released,” answered Kirsch. “Once we were successful at that, we undertook a second meta-analysis which now included

all

the studiesâboth published and unpublished.”

As the results came in from this second meta-analysis, Kirsch grew even more alarmed. They showed that the results of his first study were plainly wrong: antidepressants did not work

moderately better

than placebos; they worked

almost no better at all

.

3

Moving away for a moment from the cozy sitting room in which Kirsch was recounting his unsettling series of discoveries, let's backtrack a little so I can illustrate to you how the studies into antidepressants that Kirsch's meta-analysis surveyed were conducted.

To do this, imagine yourself in the following scenario: You've been depressed for at least two weeks (the minimum time needed to be classed as depressed, as you'll recall from Chapter 1). So you eventually decide to drag yourself to your doctor, who asks you if you would like to participate in a clinical trial. The aim of this trial is to test the effectiveness of a new antidepressant drug (which may cause some side effects if you take it).

Your doctor then explains how the trial will work: before you are given the antidepressant, your level of depression will be measured on something called the Hamilton Scale. This is a scale that runs from 0 to 51, and the task is to work out where you sit on this scale.

Your doctor explains that all the trial researcher will do to work out where you sit is ask you a number of questions about yourself, such as whether you are sleeping well, whether you have an appetite, whether you are suffering from negative thoughts, and so on. You'll then be given points for each of the answers you give. For example, if you answer that you are sleeping well, you'll be given one point, whereas if you say you are hardly sleeping at all, you'll be given four points. The more points you accumulate, the higher you are rated on the scale, and the higher you are rated on the scale, the more likely you are to be classed as depressed. That's how the Hamilton Scale works: If you're rated at 26, you're thought to be more depressed than if rated at 19. You've got the idea.

After this initial assessment, the trial researcher will then place you in one of two groups of patients and prescribe a course of pills. But there's a catch. You'll be told that only one group of patients will be prescribed the real antidepressant, while the other group will be given a “placebo pill”âa pill that is made of sugar and which therefore contains no active chemical properties. No one will be told which group they are in, nor will anyone know what pill they are taking until their treatment has ended some three months later and their levels of depression have once again been measured on the Hamilton Scale. Your first rating (pre-treatment) and second rating (post-treatment) will then be compared.