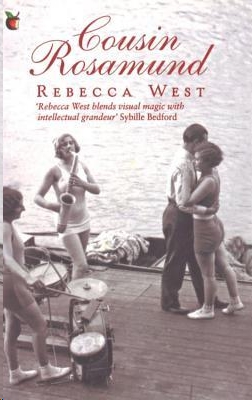

Cousin Rosamund

Authors: Rebecca West

Cousin Rosamund

Rebecca West

Contents

N

OTHING

was ever so interesting again after Mamma and Richard Quin died. I cannot think that any two human beings have ever been more continuously amused and delighted than Mary and I had been after Cordelia had married and we were left alone with our mother and brother and Kate. But though it was worse than hunger and thirst to miss the warmth and surprise and laughter we were excused the most cruel components of grief. We had not to ask ourselves where our dead had gone and to admit that their destination might be no further than rottenness, and to abhor the criminal waste. Our dead were like the constellations; we could not touch them but we could not doubt their existence. We knew them to be magnificently engaged, and though we could have wished an end of effort for them, we knew that their destiny was as native to them as music was to us. But we had to leave Lovegrove. Our house could have seduced us into the practice of magic; we might have re-created the past and inhumed ourselves in it.

So we let Alexandra Lodge to a composer and his violinist wife, who were glad of the music-rooms, and Mr Morpurgo found us a house in St John’s Wood. Rosamund was still working in a Paddington hospital and would always have to be near Hariey Street and the nursing-homes, and had taken a flat with her mother near Baker Street, and we chose that particular district because of all North London it is most like South London. There is the same repressed woodland against which the masonry just holds its own, and at night the shadows of the branches lie in as undisturbed a pattern on the quiet pavements, and the street-lamps shine with the same soft yellow submissiveness under the weight of the quiet night, and the houses with their lit windows look like fortresses withstanding that night. We liked the long classical church that stands in a grove at the corner opposite Lord’s, with a girl kneeling on a monument among the trees, her long hair falling over her humble shoulders, her face upturned in the ambition of prayer. If we were driving home together at night we often stopped the car just there and looked through the railings at her and walked the rest of the way home.

The house Mr Morpurgo had found for us was a union of two houses of the same period as our Lovegrove cottage, with the two coach-houses on each side enlarged into music-rooms. It was so large that Kate became a cook-housekeeper and had another servant and a charwoman under her, and often wore a black silk dress with a huge cameo brooch at her throat which made her look like the housekeeper in a Brontë novel. This delighted Mr Morpurgo, who approved our habit of wearing Empire dress in the evenings and had filled our rooms with exquisite Empire furniture and had chosen for us Empire stuffs for curtains and upholstery. Because our dresses were like stage dresses, and because the home he made for us was like a stage setting, we were in some danger of becoming more like objects than people. But indeed we had no choice about the clothes. When we first grew up clothes were quite beautiful, though they were nearly always too bulky, and they had a feature which helped all women to look elegant. Sleeves were then very elaborately made, by seamstresses who never touched any other part of the dress. They were cut in several long strips, which were designed to lend every arm favourable proportions. But as we grew through the late twenties, there rose the star of Chanel, who imposed on women the most hideous uniform that they have ever worn. The gravest of us had to go about by day in straight skirts up to our knees, with wide belts round our hips, and our heads buried in flower-pot hats that covered our foreheads, and by night in dresses that were as short and even more ridiculous in form. They were cut with square necks and plain shoulder-straps, so that at a dinner-party the women might have been sitting round the table in bathing-dresses; and they were often embroidered all over with heavy beads, so that the hem formed a sagging frill above the calves. But there was an alternative for the evening in the

robes de style

which Lanvin had just invented for Yvonne Printemps, and though these were eighteenth-century dresses their acceptance gave us permission to wear our Empire dresses. These were indeed beautiful, and old photographs show that they gave Mary’s swan-like beauty its full opportunity; and though I cannot look at my photograph and see it any more than I can look at my own image in a looking-glass, I can see that in those dresses I was an interesting spectacle. But to be that, and only that, often seemed a misfortune which continually threatened Mary and myself, though we were always rescued from it by a certain force.

I remember very well a certain autumn day which illustrated our plight. I had gone to Paris for a most interesting concert at the Salle Gaveu. I had taken the opportunity to play some solos by the Russian composers, but the main purpose of the evening was the first performance of a concerto by Louis Besricke, who was still working in the Debussy and Fauré tradition though he indulged in greater technical complexities. Everything was paid for by a Jewish millionaire and we had more than the usual number of rehearsals, as many as even the composer wanted. On the first day it appeared that the interpretation of the concerto which I had evolved while working on it in London was not correct, and the bearded composer stopped me and said, smiling, ‘Mais, mademoiselle, vous êtes trop mâle pour mon frêle oeuvre.’ The orchestra looked at me with that tender and gracious amusement which a group of men can feel for one woman, though it is rarely felt by one man for one woman, and never by a group of men for a group of women. After that it was all a laughing and sentimental adventure, the rehearsals all seemed to last no more than ten minutes. But not only the rehearsals, the whole of each day was lovely. I used to leave my hotel early before anybody could telephone and walk along the rue de Rivoli, with the first tarnished chestnut leaves blowing over from the Tuileries Gardens, and along the Avenue Gabriel, past the Jockey Club and its tamarisk hedge, always looking through the trees at the Théâtre Marigny and wishing I could have been an actress as well as a pianist, just for the sake of playing at that theatre, and going up to the Arc de Triomphe by the Champs Elysées, then still noble and intact, with not a shop to be seen. There was even still standing that countryish house on the right, where great dogs were always softly belling behind the high garden walls; it had the air of a place where people were living out the long consequences of some violent action. I would go to my practising and my rehearsal inspired by this local excellence; and when I had done with music for the day the city refreshed me again, though not so much as in my lonely mornings, for my French contemporaries alarmed me. After the First World War it had become fashionable in Paris to be silly, and an appalling measure of French intelligence and spirit, and even some of its classical spirit, was devoted to establishing silliness as a way of life. Men loved men and women loved women, not because there was a real confusion in their flesh, such as Mary and I often noted in those with whom we worked, but because a homosexual relationship must be nonsense in one way, since there can be no children, and it can be made more nonsensical still. Where there can be no question of marriage there is no reason against choosing the most perversely unsuitable partner; and often we met gifted Frenchmen who took about with them puzzled little waiters or postmen or sailors, flattered and spoiled but never acclimatised. But it was much more frightening that people of talent injected silliness into their whole structures by taking drugs; for Mary and I, like most artists, knew that drink and drugs were our natural enemies. It was hateful, too, that many of the people who were most heartless in their loves, who took up these young men and gave them luxury and loneliness and a disinclination for their own natural habits, and who smoked opium or took morphine or cocaine and became walking nightmares of malice and fear, often became Roman Catholics, and made no effort to purify themselves, though that effort would not have cost them much. From our childhood we had known the nature of darkness, we had seen Papa abducted by ruin, and we knew that all these people could have stopped what they were doing at any moment, had they chosen. These people thought we were held back from them because we knew less than they did, though of this we knew more, but they were friendly, and they liked our playing, so they asked us to their parties, and these were beautiful. They lived in huge white empty rooms, often with great windows opening on the night sky and the spread lights of the city. I went to two such parties on that visit; but I took greater pleasure in my visits to the villa by the Parc Monceau where the parents of the composer of my concerto lived.

Monsieur and Madame Besricke were like a thousand other people in Paris, and they were apparently undesirable. They were superbly handsome but deformed by pretensions. The old man, who had inherited a moderate textile fortune and had been a poet and critic of some note, wore a Rembrandt beret and disarranged his classical features by an expression intended to convey that he was wise, witty, sceptical, tolerant, kindly and sensual; and his thin wife dyed her hair mahogany red, and wound scarves about her, and sometimes cooed and sometimes tapped her words on her teeth, to show that she possessed an immense range of emotions. It was as if Anatole France and Sarah Bernhardt had gone on living after the essence of them had died, growing old and dusty in the practice of their personal tricks. But running parallel with this stale affectation was a brilliant current of joy and honesty. They saw justly what was beautiful in their son’s music and character, and what had been beautiful in their other two sons who had been killed in the war. They saw what was beautiful in my work, and if I went there in a new dress they would make me stand in the light and told me what it did for my looks. They gave me the use of their memories, and through them I know what it was like to listen to the lectures of Ernest Renan at the Collège de France, hurrying to get there as if it were a theatre, and I went to many parties given long before I was born. And they constantly cried out to each other the names of places in France which it was imperative I should visit. The hours I spent with them were somehow like those evenings at home when we sat round the fire and ate chestnuts after we had washed our hair. It was warm and happy in these rooms which were crammed with the litter always collected by nineteenth-century French celebrities, that porridge of Genoese velvets and chips off Gothic cathedrals and Persian rugs and Renaissance bronzes and Limoges enamels and wild-beast pelts and North African silverwork and Greek marbles. Though most of these objects lost their quality and meaning in this hugger-mugger, the Renaissance bronzes and the Greek marbles remained themselves. The old people loved to see me taking pleasure in them; but did not know that for me they held an ironic significance. These bronzes and marbles were made in the likeness of the gods and goddesses, whom the ancients allowed to exist on condition that they understood everything men do and enjoyed everything. Now such images of tolerance adorned only the homes of the innocent aged; and in the white rooms of contemporaries, where the most bizarre transactions were carried on, the only permitted ornaments were those neutral objects, cacti and seashells.

The concert was a success. I was not too

mâle

for my composer, and the next morning it was settled that I would play the concerto during the following year in London and Berlin and Vienna and New York and Boston. The composer had not been sure about it till the performance; he owned with a smile that he had not till then fully understood what he meant by it. The conductor and I smiled back at him, and then exchanged a secret smile, for neither of us had greatly liked the concerto till suddenly, as the music we made was heard by us and the audience, the truth was manifest in the hall. Then we had a lovely lunch at Voisin’s, with all sorts of rich things like foie gras that I would not have dared to eat before the concert, and then I took a lot of chrysanthemums to Monsieur and Madame Besricke, and we drank cherry brandy in little coloured glasses and they said that I was to come back soon, and then I took all the flowers I had been given at my concert to an old pianist who was dying in a house in Passy. Then I went to the hotel and put on an evening dress, so that I could go straight from Croydon to a concert where Mary was playing the Emperor Concerto. Then I was driven to the airport, too fast, for it was late, and people gave me more flowers and waved goodbye. As the plane mounted and the earth swung round us like a billowing skirt, I was filled with thirst for the sight and sound of my mother and my brother, and nothing that had happened to me in Paris retained any value. The one interesting phrase in a

concertante

by a worthless German composer ran through my head again and again, until we crossed the Channel, so quiet in that soft and sleepy blue that is the sea’s autumn wear, and it pierced my breastbone that I was travelling along a low passage of uninteresting air between the earth where my mother’s body lay and the outer space where I felt her to continue. But I could not feel my brother’s presence anywhere, then or when the bus took our plane-load from Croydon through South London, which was darkening, and we would have been going downstairs to see if we could help Kate with the supper, had our lives not perished.