Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court (39 page)

Read Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #England, #History, #Royalty

111

. HMC

Egmont

(1923), Vol. 2, p. 425.

112

. Hervey (1931), Vol. 3, p. 761.

113

. HMC

Egmont

(1923), Vol. 2, p.

114

. BL Add MS 75358, Lady Burlington (‘Thursday 8 o’clock’, 1737); Duchess of Marlborough to the second Earl of Stair (17 August 1737), quoted in Cunningham (1857), Vol. 1, p. cli.

115

. The Earl of Bolingbroke quoted in Walter Sichel,

Bolingbroke and his Times

, 2 vols, (London, 1901), Vol. 2, p. 357.

116

. Holland (1846), Vol. 1, p. 74.

117

. Hervey (1931), Vol. 3, pp. 767, 793.

118

.

Ibid

., pp. 760, 763.

119

. SRO 941/47/4, p. 610, John Hervey to Count Algarotti (17/28 September 1737).

120

. Ilchester (1950), p. 267.

121

. TNA LC 5/202, p. 436 (11 September 1737).

122

. Brooke (1985), Vol. 1, p. 52.

123

. Philip Yorke,

The Life and Correspondence of Philip Yorke, Earl of Hardwicke

(Cambridge, 1913), Vol. 1, p. 171.

124

. Hailes (1788), p. 92.

125

. Tillyard (2006), p. 18.

126

. HMC

Egmont

, Vol. 2 (1923), p. 436.

127

. Cambridge University Library SPCK MS D4/43, f. 26, quoted in Smith(2006), p. 219.

128

. Pennant (1791), p. 119.

EIGHT

‘May Caroline continue long

For ever fair and young! – in song.

… the royal carcass must,

Squeezed in a coffin, turn to dust.’

1(Jonathan Swift)

The appalling family wounds of summer 1737 remained unhealed that autumn, and Caroline was still eaten up with hatred for her son.

But the next conflict at court would be fought between mightier forces than the warring royals. A battle between eighteenth-century medicine and mortality was about to begin, and the scene of the struggle was to be the bed of the weakened queen.

Her fight for life would take place back at St James’s Palace, which was still in the same unsatisfactory condition as it was when the Hanoverians first came to England. Foreigners considered that there were ‘few Princes in Europe worse lodged than the

King of England’, and once the royal family was temporarily forced out of the palace by the ‘stench of a necessary house’ belonging to the tavern next door.

2

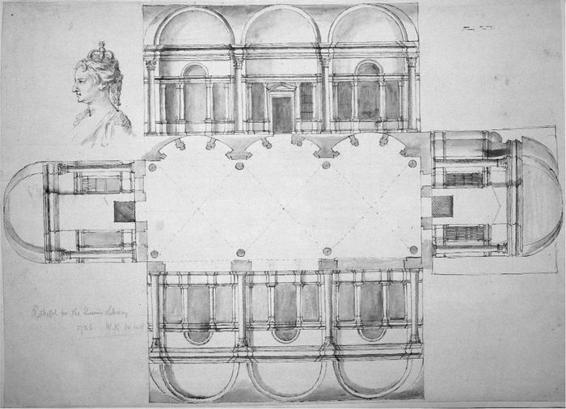

Caroline’s ‘room of her own’: the library William Kent designed for her at St James’s Palace

After many trying years as queen, the balance of Caroline’s life had shifted and was now weighted towards despair. By the later 1730s, she was feeling neglected by her husband as well as her son. As time went by, George II’s summer holidays in Hanover grew longer and longer, so much so that his family and his adoptive British subjects felt that they hardly saw him at all. Caroline constantly dwelt upon her failures as a wife and a mother: ‘her Majesty is exceeding uneasy and often weeps when alone’.

3

Caroline decided to comfort herself during one of the king’s unaccountable extended absences by beginning to build herself a new library at St James’s Palace. This was to be a room of her own, a consolation; it was a private project that would be of no conceivable interest to her husband. And it was not surprising that she turned for soothing discussions about the necessary decoration to the jovial and familiar William Kent.

Together they agreed upon a rich cornice, twenty-one bookcases, busts of philosophers and green couches trimmed with silver lace.

4

In her library, this peaceful and private place, Caroline planned to cure her cares with literature. She was certainly fond of

her three thousand books: on various occasions we hear of her laughing at

Gulliver’s Travels

; listening to literature read aloud during the tedious hours at her toilette; and sending out a Lady of the Bed-chamber to get her ‘all my Lord Bacon’s works’.

5

William Kent doodled this lovely portrait of the mature Queen Caroline at the edge of his page. She stoically insisted that she minded her husband’s infidelities ‘no more than his going to the close stool’

Caroline was impatient to put her temple of learning to use, and John Hervey was annoyed when the builders promised her unachievable progress. He wrote crossly to Henry Fox, who’d recently been put in charge of the unimproved and still inefficient Office of the King’s Works: ‘which of the devils in Hell prompted you to tell the Queen that everything in her Library was ready for the putting up of her books? – Thou abominable new broom, that so far from sweeping clean, has not removed one grain of dirt.’

6

It was in her unfinished library, on 9 November 1737, during her fifty-fifth year, that Caroline collapsed to the floor with an unbearable pain in her stomach.

*

What are we to make of the many and varied dispatches from the front line of Caroline’s battle with death, penned over the next few days as the whole nation waited with baited breath and snapped up every crumb of information available?

John Hervey’s account of the following week of Caroline’s life, covering the progress of her illness, is the great set piece of his memoirs, the most memorable, most melodramatic and blackest of all his sketches of court events.

Although it is Hervey’s horrifically gory account that has become the best known, other contemporary descriptions of Caroline’s illness were more reverent, noting that she bore pain ‘like a heroine’ and with ‘a Christian firmness and resignation of mind’.

7

And indeed the minor but telling details of the next few days would make a great impression upon the nation: ‘these little circumstances are too trivial in themselves to relate, but when they concern the last moments of Princes, are to be taken notice of’.

8

All the accounts of Caroline’s final few days, whether sensational or instructional, agreed that this uniquely testing time

would reveal her ‘greatness of soul’.

9

The queen would find her greatest strength in her weakest hour.

*

Despite the public’s unquenchable thirst for information, royal health was surrounded by secrecy. George II took great pains to disguise any chink of weakness, and John Hervey noted

a strange affectation of an incapacity of being sick that ran through the whole Royal Family … I have known the King get out of his bed, choking with a sore throat, and in a high fever, only to dress and have a

levée

, and in five minutes undress and return to his bed.

10

There were actually very good reasons for the king to maintain even a ‘ridiculous farce of health’. If the news of an illness leaked out, it would ‘disquiet the minds of his subjects, hurt public credit, and diminish the regard and duty which they owe him’.

11

Earlier in 1737, George II had suffered horribly from haemorrhoids, and he’d eventually undergone the painful operation to have them cut out. He had endured ‘violent inflammation and swelling’, and ‘his surgeon was forced to attend him with alternate applications of lancets and fomentations’.

12

The king could not bear to speak of his humiliating illness. He dismissed his solicitous servants as ‘troublesome, inquisitive puppies’ who were ‘always plaguing him with asking impertinent, silly questions about his health like so many old nurses’.

13

Caroline also suffered from the necessity of having to be present and correct in the drawing room whatever the circumstances. In the past her health had often given cause for concern. At one court occasion, ‘she found herself so near swooning’ that she had to send a message ‘to the King to beg he would retire, for she was unable to stand any longer’. That night he nevertheless made her go to a ball, and kept her there until eleven.

14

Peter Wentworth, standing and watching from the sidelines as usual, frequently found his heart smarting with concern for Caroline’s heroic fortitude. He described how he was ‘often in great pain for my good Queen, but it is not the fashion to show

any [weakness] at Court’. After another, earlier illness, he overheard her telling another courtier ‘that she had really been very bad and dangerously ill’. It was her own fault, Caroline said, for she’d kept her fever a secret and soldiered on with her social duties. ‘She owned she did wrong,’ Wentworth recalled, and she promised that ‘she would do so no more, upon which I made her a bow, as much as to say, I hoped she would do as she then said. I believe she understood me for she smiled upon me.’

15

The pain that Caroline felt in her new library, though, was too severe for her to deceive anyone: a vicious cramp in her stomach accompanied by ‘violent vomiting’. Her doctors eventually resorted to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Cordial. This powerful sedative made from alcohol and a compound of forty different roots and herbs ‘gave her some ease, and was the only thing stayed with her … She continued all night so ill that the King, the Duke and Princesses sat up with her.’

16

Like Peter Wentworth, Sir Robert Walpole hoped that Caroline’s collapse would force her to begin to take better care of herself. The day after her attack in the library, he spent an anxious hour begging her to be careful, saying, ‘Madam, your life is of such consequence to your husband, to your children, to this country, and indeed to many other countries, that any neglect of your health is really the greatest immorality you can be guilty of.’

Only she could control the king, Walpole said, she alone held the reins ‘by which it is possible to restrain the natural violences of his temper’.

‘Should any accident happen to Your Majesty,’ Sir Robert concluded, ‘who can tell what would become of him, of your children, and of us all?’

17

*

As the queen’s battle against this mysterious stomach ailment commenced, she had the comfort of knowing herself to be a brave, if bloodied, warrior in the field of medicine, and she had previously won some fabulous victories against the ignorance and conservatism of contemporary doctors. She is most renowned,

medically speaking, as a strong supporter of the practice of inoculating children against smallpox.

The mild discomfort of a few days of artificially induced illness was well worth it to avoid the full-blown version of a disease which had such a high risk of death. Smallpox first appeared as a red rash, then liquid-filled pustules gradually covered the sufferer’s entire body. The mouth, eyes and even the sexual organs became so swollen that the patient couldn’t be recognised and fought for breath as his or her throat and nose narrowed. After a week or so, the liquid in the pustules turned to yellow pus, and feverish delirium set in.

When the pustules burst they filled a sickroom with ‘a stink so intolerable, that a thousand old rotten ulcers, with their united stench of Midsummer, could not equal it’. One medic reported that he’d put a vinegar-soaked sponge in his mouth as protection against the putrid smell, but even that was inadequate: ‘as if struck with a thunder-bolt, I was instantly seiz’d with a trembling over my whole body’.

18

If the patient survived the bursting of the pustules, the prognosis was good, for then they formed incredibly itchy but harmless scabs. These slowly flaked away, leaving behind brown and finally white permanent pits in the skin. The scarred survivors known to Caroline included her own daughter Princess Anne and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (who’d lost her eyelashes to the disease).

19

And Caroline herself had suffered in her youth. It was said that she ‘was esteemed handsome before she had the small-pox, and became too corpulent’.

20

Meanwhile, far away in Asia, the secret to surviving smallpox safely had been discovered. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a former drawing-room regular, had travelled to the East as the wife of Britain’s ambassador to the Turks. In Constantinople she’d learnt how to introduce a tiny amount of smallpox pus into a child’s body to bring on a mild form of the disease, with the intention of immunising the adult against more virulent strains. The method to be followed was to

take a child of any age under ten years old, the younger the better … and find out a person that is sick of a favourable sort. When the pustules are ripe … lance some of them, and receive the matter into a nut-shell, and carry it to the place where the child is. Then with a needle, that hath been dipt into this pocky-poison … prick the fleshy part of each arm and each thigh, deep enough to fetch blood. In a little time each of these punctures begins to inflame, and rises up into a great boil, which ripens, breaks, and discharges abundance of matter. About the seventh day the symptoms of the small-pox begin to appear [but] neither the life nor the beauty of the patient is in any danger.

21