Copia (3 page)

Authors: Erika Meitner

N

IAGARA

Witness this: peonies and roses on the bedspread. Her red dress. The motel curtains sliding together to cover their view of parking lot oil stains and cigarette butts, the billboard that asks How Will The Falls Transform You? Their bodies give way, unresolved and stumbling. Afterwards, he stands in the rented doorframe listening to her shifting, her breath. In the half-melting drifts. In the creak of the car door before the slam. And how she breathes, like an accordion or a jewel box, and the sky opens. It's not the first time he prays for wonders instead of happiness. Cave of the Winds. Maid of the Mist. Rushing torrents of neon bouncing off the pavement between gaps in the motel curtains: aperture of plastic, chrome, electric light. Love is thrown and it is caught. It lives a long time in the air, floats on the surface of the skin. It can overflow, bounce like a fiddle string. It can be blurred, shaped like an onion peel. The half-moon of her body in this stained place, vertiginous. He hasn't written these words in a long time. He writes them with

the motel pen.

If there was an apartment and I had a decent job and you felt happy and thought there could be a nice history together, would you come home?

P

AST

-F

UTURE

/F

UTURE

-P

AST

I tried to write you tonight

but there was nothing to say

If you already know the highway,

semis bearing down on asphalt

If you already know someone

who moans in their sleep

If you already know about crickets

or the wires of night stretching

like a fitted sheet, like a pencil compass

rounding the lines of the moon

and her consorts and are you in bed

with a counterpart and if so

then I am sure I already wrote you

about the train, its muffled whistle-

call insomnia, or the boxwoods,

twenty feet tall, reeking of decadence

and pilfered tradition

There's a phone booth here still

older than I am and I

was old enough to be used once,

and once, too, my stories

were not repeated, did not

repeat themselves in the phone booth

or to you when most nouns of this place

were unique and strange on my

tongue: farm, gravel, hay,

and scrap and dirt and

something singing

T

ERRA

N

ULLIUS

When we were done, all the buses had stopped running.

When we were done, the moon was painted large and

low-slung on the horizon. We sat like that a long time,

listening to each other exhale blue plumes of smoke

which tucked themselves through checkered screens.

It was near-morning and we were in our underwear.

It was near-dark and we were in our underwear,

my legs draped across his lap. Gentle curvature

of smokeâour bodies were looted, were broke.

Outside, invisible wires held up water towers and

busted street lamps. The sides of semis turned

the highway to gold threads. We had hallelujah

billboards. We had industrial rust. He put his finger

to my lips and I became the wreckage so we could find

our way back. We sat like that a long time.

A

POLOGETICS

A host of angels or a compass of cherubim

or maybe a resolution of sprites has absconded

with me or my common sense or possibly just

my best self and godknowswhatelse.

Which is to say I'm sorry.

I didn't mean to go to IHOP and spend the entire time

trying not to stare at the man in a reclining wheelchair

covered with a coverlet, sucking on oxygen

near the ladies' room.

I didn't mean to write you a letter that falls into

the oversharing category or scare you with Horace

or otherwise compromise what might have been

a perfectly fine correspondence (if not for my mention

of my copious tattoos or other youthful indiscretions).

I didn't mean to get a fever on this vacation, or yell at my son

in the bathroom of the BP station because he was touching

everything including the toilet seat. He always touches

the toilet seat in every bathroom. This is not new.

I did mean to go (which is to say I purposefully went)

to the aquarium and wondered how or why everyone else

seemed perfectly content with battling the crowds to see

otters or anemones. In the tank in The Pacific Reef exhibit

there was someone in an anonymous black scuba suit

standing and waving under the water; he/she was attached

to the window with a suction cup and gesticulated constantly,

mugged for pictures, fed the fish from a squirt bottle.

I learned

Beluga

is a Russian word. The Belugas were mating.

Or at least one named Beethoven was mating with another

whose name I don't remember because it wasn't a composer.

I started playing the violin when I was fourâthe same age

as my son. My teacher, Mrs. Eley, often cut my nails

with clippers she fished out from inside her piano.

My friend H. had the lesson after mine. He was

actually talented and some Fridays Mrs. Eley would ask him

to play whatever piece I struggled through so I could hear

how it was meant to sound, which was like the Long Island Sound

out her window at duskâthe beach being lapped by deep darkness;

the way the horsehair of a rosined bow, when pulled over strings,

smokes with small curls of dust. Years later, H. was killed

by a Metro-North train at the Riverdale station; the train's

engineer saw him jump from the platform.

I can hear the train here, though it doesn't matter where here is.

Everywhere is home for someone. This place has goats

and a rooster. When the bird went cockadoodledoo this afternoon

my son told him he could stop now since everyone was already up.

It is still night. Everyone is not already up.

The family is asleep and I'm typing this in the dark.

I once lived in a cottage with lemons in the front yard.

I once lived in a two-flat with a huge crape myrtle in the front yard.

I lived in many places that had no front yards at all.

The place I live in now has a dwarf cherry tree

that never recovered from one winter's frost.

I am telling you this because I have no common sense.

R

ETAIL

S

PACE

A

VAILABLE

Because the image we make is painted

by flashlight: expired storefront, vacate

space where the elements didn't take

a toll on bits of smooth façade due to

signage: labelscar. Outskirts: because

our darks erase sirens in the distance,

pockmarked asphalt, the unknown

brightness of an indisposed place. Who

wraps us with compassion for the world

to come? The wilderness. Box elders

and couch grass crack through cement

block, return this refuge for cast-off

plastic shoes and discarded Chevys with

the squared-off trunks of three decades

ago to verdant. To once. Because we

rework time and space until both are

abandoned in a concrete grace: blown-

out sky, asperity, rippled bitumen,

monotonal hum. Because everything

beautiful is not far away. Because

one blue shopping cart knocked over,

joyridden, hears us sigh goodbye

twentieth century and the disposable

store glows quietly from within. In

the image of plenty we created them.

Because though this world is changing,

we will remain the same: abundant and

impossible to fill.

II

M

APLE

R

IDGE

It rains and rains here. Steady.

In fits and starts. The rain bounces

off the screens like tentative bees,

like tacks pelted by an unseen hand.

We haven't left the house for forty days,

jokes Pastor Vince from his slick

deck next door. Every lawn

on the block has melded together,

grown to a meadow punctured

with delicate ecosystems of fungus

and calamity. The other neighbor's

boy runs through our yard

with a flower-shaped bruise

where his arm meets his chest.

His stepfather chases him down,

stops to show us a matched one

yellowing near his own shoulderâ

recoil from the AK

, he says proudly.

He was wantin to fire a 12-gauge shorty

at the range, but that woulda been

too much for him.

Logan is

almost nine, so Give-Us-

Help-From-Trouble, O Lord,

Sunday's sermon at Pastor

Vince's congregation on bring-

your-weapon-to-church day:

“God, Guns, Gospel, & Geometry”

says the message board outside

Fieldstone, his parishioners packing

in the pews while we get on our knees

to tear out yellow networks of flowers

which outpace our violent efforts,

white and purple clover

that smell like wind and sugar

when they're beheaded by the mower.

We smooth things over

slowly.

Children! Don't rush.

The month of May has arrived.

Now the rain is harder. The house

tears at its seams, vinyl-siding

stretching to accommodate

air, water, elemental gravities

that seep in while we sleep.

The wind does not howl.

It surgically disassembles

each set of metal chimes

we hang from the porch eaves.

It nods the tall grass

then tramples it like a pack

of roving dogs. Our small son

learned to open doors on his own

some time ago. When the rains stop.

When the rains never stop.

Somewhere a boy has a pistol

blazing a hole in his pocket

the size of the moon. The door

howls like the wind does not.

Somewhere a boy has an automatic

assault rifle. Flecks of rain

freckle his face.

Careful

.

The drops are not neutral.

Y

IZKER

B

UKH

Memory is

flotsam (yes) just

below the surface

an eternal city

a heap of rubble

debris smaller

than your fist

an animal with-

out a leash

organized wreck-

age ghost net

or one hanging

silence on the phoneâ

she's gone

, my sister said,

and we wept and wept

over my grandmother

while my sister sat

with her body and me

in the static and the rabbi

they sent told her to recite psalms

as comfort so we listened to each other

breathe instead and my sister's breath was

a tunnel a handful of pebbles a knotted

Chinese jump-rope        her breath was the coiled

terrycloth turban our grandmother wore when she cooked

or walked the shallow end of her condo pool for exerciseâ

our grandmother still somewhere in her white turban sewing

Cornish game hens together with needle and string or

somewhere in her good wig playing poker or

somewhere in her easy chair watching CNN

while cookies shaped like our initials bake

in her oven O memory how much you

erased how many holes        we punched

in your facts since who knows the stories

she never told about the camps there are

no marked graves just too much food on

holidays diabetes my mother's fear

of ships and the motion of some

suspension bridges O memory

you've left us trauma below

the surface and some above

like the fact that I can't

shake the December

my sister's red hair

caught fire from

leaning too close

to the menorah's

candles, our

grandmother

putting her

out with a

dish towel

with her

strong

arms.

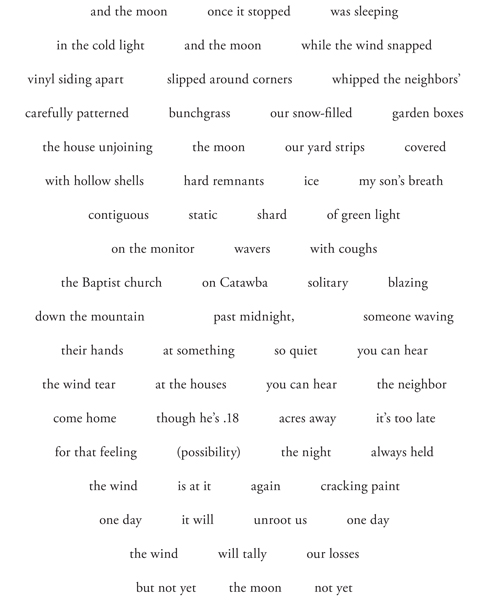

A

ND THE MOON

shut in cold blue light,

in blown snow, my son's

static breath a forgiveness

a roadside x a since a wind-

shield a tunnel a handful

of pebbles.

Y

IDDISHLAND

The people who sang to their children in Yiddish and worked in Yiddish

and made love in Yiddish are nearly all gone. Phantasmic. Heym.

Der may kumt shoyn on

. The month of May has arrived. At the cemetery

my aunt has already draped my grandmother's half of the tombstone

with a white sheet. The fabric is tacked to the polished granite

by gray and brown rocks lifted from my grandfather's side of the plot.

He's been gone over twenty-five years. We are in Beth Israel Cemetery,

Block 50, Woodbridge, New Jersey for the unveiling and the sky is like lead.

We are in my grandmother's shtetl in Poland, but everyone is dead.

The Fraternal Order of Bendin-Sosnowicer Sick & Benevolent Society

has kept these plots faithfully next to their Holocaust memorialâ

gray stone archway topped with a menorah and a curse:

Pour out Thy wrath

upon the Nazis and the wicked Germans for they have destroyed the seed of Jacob.

May the almighty avenge their blood. Great is our sorrow, and no consolation is to be found!

My sister, in her cardboard kippah, opens her prayer bookâa special edition

she borrowed from rabbinical schoolâand begins to read in Aramaic.

Not one of us can bring ourselves to add anything to the fixed liturgy.

My son is squatting at the next grave over, collecting decorative stones

from the Glickstein's double plot. We eat yellow sponge cake and drink

small cups of brandy to celebrate my grandmother's life. We are no longer mourners,

says Jewish law. Can we tell this story in Yiddish? Put the words in the right places?

My son cracks a plastic cup until it's shredded to strips, looks like a clear spider,

sounds like an error. When my sister finally pulls back the sheet, all the things

my grandmother was barely fit on the face of the marker. A year ago at the funeral,

her friend Goldie told me she was strong like steel, soft like butterâ

women like that

they don't make any more.

My mother tries to show my grandmotherânow this gray markerâ

my son, how he's grown, but he squirms from her arms.

Ihr gvure iz nit tzu beshraiben.

Her strength was beyond description. The people who sang to their children in Yiddish

and admonished them in Yiddish are nearly all gone, whole vanished towns that exist now

only in books, their maps drawn entirely by heart: this unknown continent, this language

of nowhere, these stones from a land that never was.

Der may kumt shoyn on.

The month of May has arrived.

Der vind voyet

. The wind howls,

says I'm not a stranger anywhere. On the stones we write all we remember,

but we are poor guardians of memory. Can you say it in Yiddish? Can you bless us?