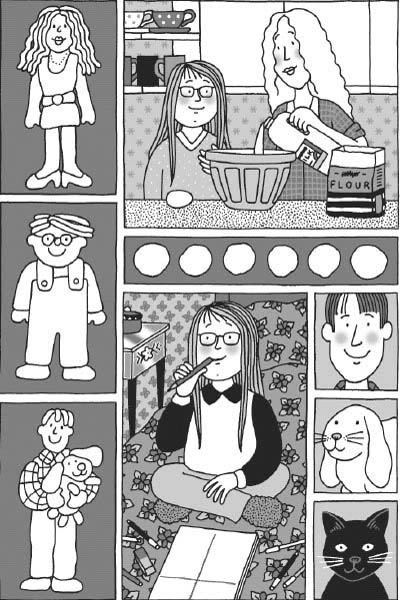

Cookie (9 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

‘I think you’ll have to invent a

nice

nickname for yourself,’ said Mum. ‘Let me think.’

She drove slowly, humming along to the music on the car radio.

‘They used to call me Dilly Daydream at school. And your dad used to be called Cookie because of his surname.

Your

surname. Can’t your new nickname be Cookie?’

I thought about it. I quite liked the name Cookie. It sounded funny and bouncy and happy. Not really like me.

‘I can’t just get them to start calling me Cookie,’ I said. ‘It doesn’t really work like that, Mum.

They

decide what they’re going to call me.’

‘Mm,’ said Mum again. ‘Well, we’ll find a way of

encouraging

them along the Cookie route.’

She took one hand off the steering wheel and patted my shoulder sympathetically. She very gently tugged a lock of my damp hair. ‘That was a bit of a waste of fifty quid,’ she said.

‘Will Dad be mad, do you think?’ I asked.

‘Maybe,’ said Mum, sighing.

Dad

was

mad. He usually came home jolly after a day’s golf but we knew as soon as we heard the door slam and the

thump thump

as he threw his shoes in the rack that he was furious. He stamped into the living room in his socks and poured himself a large whisky, barely looking at us.

‘Oh dear,’ said Mum, in her sweetest trying-to-please voice. ‘Didn’t you have a good game, darling?’ She made a little shooing motion to me so I started sidling out of the room.

‘I won both games, as a matter of fact,’ said Dad, glaring at her. ‘My golf swing is pretty lethal at the moment – and I was playing with a bunch of blithering idiots. I just don’t

get

it. I’ve given them every incentive. It would be so

simple

for them to fix things for me, but they all witter on about their hands being tied. It’s so frustrating sucking up to the lot of them all day long and getting nowhere, absolutely blooming nowhere.’

I dithered in the doorway.

‘Is this the Water Meadows deal?’ said Mum. ‘I thought you said it was all sewn up.’

‘Some cowardly nincompoop unstitched it all. He says there’s no way they’ll ever grant planning permission.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Mum.

‘Oh dear! That’s a bit of a limp reaction. Is that all you’ll say when the guys I owe start clamouring for their money and I haven’t got the wherewithal to pay them? Will you just say “Oh dear” when the entire business goes down the pan and we’re out of this lovely house, sitting in the gutter looking stupid?’

I crept into the hall, biting my nails.

‘Gerry, don’t. You know you’ll sort things out, you always do. Come on, put your feet up, relax a little. Shall I run you a hot bath?’

‘You can get me a hot

meal

; I’m starving. Shove any old muck in the microwave, as if I care. I didn’t pick you for your culinary skills, I picked you for your looks.’

I hated the way Dad talked to Mum as if she was some silly doll.

‘Hot meal coming right up, darling,’ said Mum.

She

sounded

like a doll too, as if someone had pulled a tab in her back to make her parrot a few silly phrases. I knew she was simply trying to sweet-talk him out of his mood but it still made me squirm.

It seemed to be working though.

‘You’re certainly looking good tonight, babe,’ Dad said. ‘Like the hair! It’s perked up a treat. So what about Beauty? Let’s see

her

new hairdo.’

‘Oh, Beauty’s upstairs,’ Mum said loudly. ‘She got tired out at her party.’

I scooted up the stairs two at a time but I was still wearing Mum’s high heels. I tripped over, bumping my knees.

‘Beauty?’ said Dad, going to the door. ‘Oi, Beauty, I’m talking to you. Come downstairs into the light. Let’s have a proper squint at you.’

I walked down the stairs, holding my breath.

‘Good God, you’re a right sight!’ said Dad. ‘You look uglier than ever!’

I felt the tears pricking my eyes. I pressed my lips together, trying hard not to cry.

‘Gerry, shut up,’ said Mum.

‘Don’t you dare tell me to shut up in my own house!’ Dad said. ‘What in God’s name have they done to the kid? She’s all over rat’s tails.’

He took hold of me and tugged my hair in disgust.

‘Stop it! Don’t you dare hurt her!’ said Mum.

‘I’m barely touching her. So did you actually pay good money –

my

good money – for this terrible hairdo, Dilly?’

‘It was a silly idea to start with. Beauty’s just a little girl, she doesn’t need fancy hairdos. It didn’t really suit her, all those curls. Then it was a swimming party, so of course she got wet.’

‘I thought you were just going to paddle, Beauty?

What

’s the matter with you? Whatever made you dunk yourself head-first in the pool and ruin your hair? Don’t you

want

to look pretty? Don’t pull that silly face, nibble nibble at your lip like a blessed rabbit. Stand up

straight

, don’t hunch like that, sticking out your stomach!’

‘Don’t say another word to our lovely daughter! Beauty, go upstairs, darling,’ said Mum.

I ran upstairs to my bedroom. I put my hands over my ears so I couldn’t hear them arguing about me. I saw myself in my Venetian glass mirror. I tried brushing my hair. It stuck limply to my head. I looked at my big face and my fat tummy and my ridiculous clothes. Dad was right. I did look a sight.

No wonder Skye and Arabella and Emily and all the other girls called me Ugly. It wasn’t just a play on words because of my silly name. I really was ugly ugly ugly. It was like staring into one of those distorting mirrors at the fairground. My hair drooped, my face twisted like a gargoyle, and my body blew up like a balloon. My clothes shrank smaller so that my blouse barely buttoned and my skirt showed my knickers.

I seized my hairbrush and threw it at my image in the mirror. There was a terrible bang and I saw myself crack in two. I gaped in horror.

I

’d smashed the mirror, the ornate Venetian glass mirror Dad had bought specially for my bedroom. A long crack zig-zagged from the top to the bottom of the glass.

I shut my eyes tight, praying that it was all a mistake, an optical illusion because I was so upset. I opened my eyes a fraction, peering through my lashes. Everything was blurry – but I could still see the ugly crack right across the mirror.

I kicked the hairbrush across the room. Then I sagged onto the carpet, down on my knees. I clenched my fists. I was still holding Reginald Redted in my left hand. Why hadn’t I hurled

him

? He’d have bounced off the glass and somersaulted to the floor, no harm done. I held onto him. He looked back at me quizzically.

‘I am in

such

trouble,’ I whispered. ‘Dad always goes totally mad if I break anything, even if it’s a total accident. When he sees the mirror he’ll realize I threw the brush on purpose.’

I rocked backwards and forwards. I could hear the angry buzz of his voice downstairs. He was obviously still ranting about his ugly, freaky daughter.

‘I hate him,’ I whispered. ‘I can’t

help

being ugly. He’s my

dad

, he’s meant to

like

the way I look. He’s meant to be kind and funny and gentle, just like

Rhona

’s dad. Oh, I wish wish wish I could swap places with Rhona.’

Reginald Redted tilted his head at me. He seemed to be nodding. It looked like he longed to be back with Rhona instead of stuck with me.

DAD WENT OFF

to golf again early the next morning. The minute he slammed the front door Mum jumped out of bed and pattered along the landing.

‘Beauty? Are you awake, sweetheart? Hey, can I come and have a cuddle with you this time?’

‘No, Mum! Don’t come in!’ I said.

‘What? Why not? What is it?’ said Mum, opening my bedroom door. ‘Are you still sleepy? Do you want to snuggle down by yourself?’

‘Yes. No. Oh, Mum!’ I wailed.

Mum came right into my room and switched on the light. I looked desperately at the mirror, wondering if it could have magically mended itself during the night. The crack looked uglier than ever.

Mum’s head jerked when she saw it, her hand going over her mouth.

‘Oh, lordy! A broken mirror, seven years’ bad luck! However did it happen?’

‘Don’t be cross, Mum!’ I begged.

‘Don’t be nuts, when am I ever cross with you?’ said Mum, coming over to my bed. She put her

arms

round me and hugged me tight. ‘What did you do? Did you knock against it somehow? Don’t worry, I know it was an accident.’

‘No it wasn’t, Mum. I did it deliberately,’ I said, in a very small voice.

‘Deliberately?’ Mum echoed, astonished.

‘I threw my hairbrush at it – at

me

, my reflection,’ I said.

‘Oh dear,’ said Mum, and she started crying.

‘I’m so sorry, Mum. I’ll pay for it out of my pocket money,’ I said. ‘Please don’t cry.’

‘I’m crying because your dad was such a pig to you, making you so unhappy. He was talking stupid rubbish, sweetheart. You look

lovely

. When your hair’s natural it’s all soft and shiny, you’ve got beautiful eyes, rosy cheeks, gorgeous smooth skin. Don’t you dare let him put you down, baby.’

‘He puts

you

down.’

‘Yes, I know. Well, I’m going to try and stand up to him more. I know he’s dead worried about his work but that doesn’t mean he can just be hateful and take it out on us,’ said Mum. She looked at the mirror, running her finger down the long crack.

‘Could we mend it somehow?’ I asked.

‘Don’t be daft,’ said Mum.

‘So what are we going to

do

?’

‘Simple. We’ll buy another one and we’ll sneak this broken one out to the dump.’

‘But they cost hundreds of pounds, Mum, you know they do. I’ve got seven pounds left out of my pocket money after buying Rhona’s birthday present.’

‘

I’ll

buy the new mirror, silly.’

‘But you haven’t got any money, Mum.’

Dad didn’t want Mum to go out to work now, not even at Happy Homes. He said her job was to make

our

home a happy one. He didn’t give her an allowance out of his money. She had to ask for everything. Dad didn’t even let her have her own credit card.

Mum was nibbling at one of her nails, thinking about it.

‘I’ll sell some stuff,’ she said. ‘Some of my rings, or maybe a necklace.’

‘But that’s not fair on you, Mum. It was me that broke the mirror. Shall I sell some of

my

jewellery?’

I had a gold chain with a tiny real diamond and a silver bangle and some turquoise beads and a small gold signet ring with my initial on.

‘I don’t think your jewellery would fetch much, Beauty. I’ve got masses of stuff. I’ve sold one or two bits to that jeweller’s near the market before when I’ve needed to.’

‘Oh, Mum.’ I knew she spent the money on me. Every so often Mum took me up to London on Saturdays to go to art galleries. We never told Dad. He

hated

art: he said all Old Master paintings were boring religious stuff and all modern art utter rubbish and a con. I’m not sure Mum really liked going round all the galleries either. She often yawned and rubbed her back, but she still tottered around gamely in her high heels. She bought me postcards of all my favourite paintings and I pasted them into scrapbooks so that I had my own mini-gallery to look at whenever I liked.

‘If I get to be an artist when I’m grown up I’m going to treat you to so many different lovely things, Mum,’ I said.

‘I think artists are supposed to starve in garrets,’ said Mum. ‘Maybe we’ll both be living on dry biscuits and water. Ah, that reminds me! Do you fancy doing some baking this morning?’

‘Baking?’ I stared at Mum.

‘Yeah, why not?’ she said. ‘I thought I’d have a go at making cookies. Then you could maybe take them to school, to share them round?’

I suddenly saw where she was coming from. ‘So they’ll start calling me Cookie?’

‘We could try it, eh?’

‘Oh, Mum, you are sweet. But …’ I hesitated. ‘Do you know how to bake cookies?’

‘Of course I do,’ said Mum. ‘Well. It can’t be that difficult. Remember that time we made cakes together?’

I remembered. They weren’t proper cakes, they were just made from a cake-mix packet, and even so we got them wrong, adding too many eggs because we thought it would make them taste nicer. We put them right at the top of the oven, hoping that would make them go golden. They didn’t do this at all, they burned themselves black, though the insides were all sloppy and scrambled. We still iced them and I ate them all up, insisting they were delicious. Maybe this had been a mistake.

‘Have you got a cookie packet mix, Mum?’

‘I’m not sure they do them. We’ll just have to make it all up from scratch,’ said Mum.

We had breakfast first, spooning down our cornflakes. Then we rolled up our sleeves and got cracking on the cookies. Mum found an old bag of flour at the back of the cupboard. It had been there since I used flour-and-water paste when I was at nursery school. Mum cracked in an egg and stirred in some milk. Then she kneaded and I kneaded. We both got our great lumps of cookie dough and thumped them around on the table until they were lovely smooth balls.