Contested Will (3 page)

Authors: James Shapiro

I've not been able to discover who forged the Cowell manuscript; that mystery will have to be solved by others. His or her motives (or perhaps their) cannot fully be known, though it's worth hazarding a guess or two. Greed perhaps figured, for there is a record of payment for the manuscript of the not inconsiderable sum of

£

8 8s â though this document may have been planted and we simply don't as yet know when or how the Cowell manuscript became part of the Durning-Lawrence collection. But, given how much time and care went into the forgery, a far likelier motive was the desire on the part of a Baconian to stave off the

challenge posed by supporters of the Earl of Oxford, who by the 1920s threatened to surpass Bacon as the more likely author of Shakespeare's works, if in fact he had not done so already. A final motive was that it reassigned the discovery of Francis Bacon's authorship from a âmad' American woman to a true-born Englishman, a quiet retiring man of letters, an Oxford-educated rector from the heart of England. Wilmot also stood as a surrogate for the actual author of Shakespeare's plays: a well-educated man believed to have written pseudonymously who refused to claim credit for what he wrote and nearly denied posterity knowledge of the truth.

All of the major elements of the authorship controversy come together in the tangled story of Wilmot, Cowell, Serres and the nameless forger â which serves as both a prologue and a warning. The following pages retrace a path strewn with a great deal more of the same: fabricated documents, embellished lives, concealed identity, calls for trial, pseudonymous authorship, contested evidence, bald-faced deception, and a failure to grasp what could not be imagined.

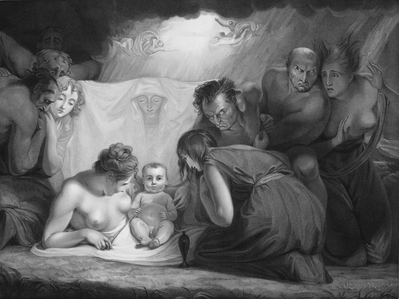

George Romney, âThe Infant Shakespeare Attended by Nature and the Passions', engraved by Benjamin Smith, 1799

Portrait, from Samuel Ireland,

Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments under the

Head and Seal of William Shakspeare

(London, 1796)

For a long time after Shakespeare's death in 1616, anyone curious about his life had to depend on unreliable and often contradictory anecdotes, most of them supplied by people who had never met him. No one thought to interview his family, friends or fellow actors until it was too late to do so, and it wasn't until the late eighteenth century that biographers began combing through documents preserved in Stratford-upon-Avon and London. All this time interest in Shakespeare never abated; it was centred, however, on his plays rather than his personality. Curiosity about his art was, and still is, easily satisfied: from the closing years of the sixteenth century to this day, his plays could be purchased or seen onstage more readily than those of any other dramatist.

Shakespeare did not live, as we do, in an age of memoir. Few at the time kept diaries or wrote personal essays (only thirty or so English diaries survive from Shakespeare's lifetime and only a handful are in any sense personal; and despite the circulation and then translation of Montaigne's

Essays

in England, the genre attracted few followers and fizzled out by the early seventeenth

century, not to be revived in any serious way for another hundred years). Literary biography was still in its infancy; even the word âbiography' hadn't yet entered the language and wouldn't until the 1660s. By the time that popular interest began to shift from the works themselves to the life of the author, it was difficult to learn much about what Shakespeare was like. Now that those who knew him were no longer alive, the only credible sources of information were letters, literary manuscripts or official documents, and these were either lost or remained undiscovered.

The first document with Shakespeare's handwriting or signature on it â his will â wasn't recovered until over a century after his death, in 1737. Sixteen years later a young lawyer named Albany Wallis, rummaging through the title deeds of the Fetherstonhaugh family in Surrey, stumbled upon a second document signed by Shakespeare, a mortgage deed for a London property in Blackfriars that the playwright had purchased in 1613. The rare find was given as a gift to David Garrick â star of the eighteenth-century stage and organiser of the first Shakespeare festival â and was subsequently published by the leading Shakespeare scholar and biographer of the day, Edmond Malone. Malone's own efforts to locate Shakespeare's papers were tireless â and disappointing. His greatest find, made in 1793 (though it remained unpublished until 1821), was the undelivered letter mentioned earlier, addressed

to

Shakespeare by his Stratford neighbour Richard Quiney.

A neighbour's request for a substantial loan, a shrewd real-estate investment and a will in which Shakespeare left his wife a âsecond best bed' were not what admirers in search of clues that explained Shakespeare's genius had hoped to find. What little else turned up didn't help much either, suggesting that the Shakespeares secretly clung to a suspect faith and were, moreover, social climbers. Shakespeare's father's perhaps spurious Catholic âTestament of Faith' was found hidden in the rafters of the family home on Henley Street in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1757, though mysteriously lost soon after a transcript was made. And the Shakespeares' request in 1596 for a grant of a coat of arms â

bestowing on the Stratford glover and his actor son the status of gentlemen â surfaced in 1778, and was published that year by George Steevens in his edition of Shakespeare's plays. Contemporaries still had high hopes that âa rich assemblage of Shakespeare papers would start forth from some ancient repository, to solve all our doubts'. For his part, a frustrated Edmond Malone blamed gentry too lazy to examine their family papers: âMuch information might be procured illustrative of the history of this extraordinary man, if persons possessed of ancient papers would take the trouble to examine them, or permit others to peruse them.'

Some feared that Shakespeare's papers had been, or might yet be, carelessly destroyed. The collector and engraver Samuel Ireland, touring through Stratford-upon-Avon in 1794 while at work on his

Picturesque Views on the Upper, or Warwickshire Avon

, was urged by a Stratford local to search Clopton House, a mile from town, where the Shakespeare family papers might have been moved. Ireland and his teenage son, William-Henry, who had accompanied him, made their way to Clopton House, and in response to their queries were told by the farmer who lived there, a man named Williams,

By God I wish you had arrived a little sooner. Why it isn't a fortnight since I destroyed several baskets-full of letters and papers; ⦠as to Shakespeare, why there were many bundles with his name wrote upon them. Why it was in this very fireplace I made a roaring bonfire of them.

Mrs Williams was called in and confirmed the report, admonishing her husband: âI told you not to burn the papers, as they might be of consequence.' All that Edmond Malone could do when he heard this dispiriting news was complain to the couple's landlord. The unlucky Samuel and William-Henry Ireland went back to London.

They didn't return empty-handed, having purchased an oak chair at Anne Hathaway's cottage. It was said to be the very chair in which Shakespeare had wooed Anne, and it's now in the possession of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Samuel Ireland

added it to his growing collection of English heirlooms that included the cloak of the fourteenth-century theologian John Wyclif, a jacket owned by Oliver Cromwell and the garter that King James II wore at his coronation. But the great prize of Shakespeare's signature continued to elude him. It probably didn't help Ireland's mood that his lawyer and rival collector Albany Wallis, who thirty years earlier had discovered Shakespeare's signature on the Blackfriars mortgage deed, had recently regained access to the Fetherstonhaugh papers and located a third document signed by Shakespeare, the conveyance to that Blackfriars transaction.

As the eighteenth century came to a close, the long-lost cache of Shakespeare's papers â and not just legal transactions, but more revelatory correspondence, literary manuscripts and perhaps even commonplace books (in which Elizabethan writers recorded what they saw, heard and read) â still awaited discovery. And crucial information about the Elizabethan theatrical world, which might have illuminated Shakespeare's professional life, was only fitfully coming to light. A major find in 1766 â a copy of

Palladis Tamia

, Francis Meres's published account of the Elizabethan literary world in 1598 â confirmed that by then a âhoney-tongued Shakespeare' was already prized as the leading English writer of both comedies and tragedies. While the contours of Shakespeare's professional world were slowly becoming visible, his personal life remained obscure. Though unsuccessful in his search for Shakespeare's notebooks, a dogged Edmond Malone did find the record-book of one of the Jacobean Masters of the Revels in a trunk that hadn't been opened for over a century. It was a discovery, Malone wrote, âso much beyond all calculation or expectation, that, I will not despair of finding Shakespeare's pocket-book some time or other'.

Despite the belated efforts of eighteenth-century scholars and collectors, no document in Shakespeare's hand had as yet been found that linked him to the plays published under his name or attributed to him by contemporaries. The evidence for his authorship

remained slight enough for a foolish character in a play staged in London in 1759 â

High Life Below Stairs

â to wonder aloud, âWho Wrote Shakespeare?' (when told that it was Ben Jonson, she replies: âOh no! Shakespeare was written by one Mr Finis, for I saw his name at the end of the book'). And in 1786 an anonymous allegory called

The Learned

Pig

was published, a story that turns on the Pig's various reincarnations, including one in Elizabethan times when the Pig encountered Shakespeare â who then took credit for the animal's work, or so the Pig claims: âHe has been fathered with many spurious dramatic pieces:

Hamlet, Othello, As You Like It, The Tempest

, and

A Midsummer Night's Dream

,' of âwhich I confess myself to be the author'. Both of these fictional works joke about authorship, but do so with a slightly uneasy edge, testifying to the growing divide between Shakespeare's fame and how little was known for sure about the man who wrote the plays.Â

*

Young William-Henry Ireland, eager to please his disappointed father, continued hunting for Shakespeare's papers among the various documents he came across as a law clerk as well as among the wares of âa dealer of old parchments' whose shop he âfrequented for weeks'. In November 1794 he was invited to dinner by a family friend, at which (to quote Malone's account) William-Henry made the acquaintance of âMr H.', a âgentleman of large fortune, who lived chiefly in the country'. Their âconversation turning on old papers and autographs, of which the discoverer said he was a collector, the country-gentleman exclaimed, “If you are for

autographs

, I am your man; come to my chambers any morning, and rummage among my old deeds; you will find enough of them.”' The young man did just that, discovering in a trunk a mortgage deed, written at âthe Globe by Thames' and dated 14 July 1610, with the seal and signature of William Shakespeare.

Mr H., in whose home it was found, preferred to remain anonymous; he made a gift of it to his young visitor and two weeks later, on 16 December, William-Henry gave his father an early

Christmas present. An overjoyed Samuel Ireland took it to the Heralds' Office for authentication, where Francis Webb declared that it bore ânot only the signature of his hand, but the stamp of his soul, and the traits of his genius'. Webb had difficulty deciphering the seals, so Ireland consulted with the economist Frederick Eden. Eden also confirmed the document's authenti city and explained to the Irelands that Shakespeare's seal contained a quintain â a device used to train knights in handling lances â wittily suited to âShakespear'.

Samuel Ireland, along with friends who viewed this deed, hoped that âwherever it was found, there must undoubtedly be all the manuscripts of Shakespeare so long and vainly sought for', and urged William-Henry to return to the gentleman's house and search more thoroughly. William-Henry did so, and further searches produced a treasure-trove of papers, including a receipt from Shakespeare to his fellow player John Heminges, Shakespeare's own Protestant âProfession of Faith', an early letter from Shakespeare to Anne Hathaway, a receipt for a private performance before the Earl of Leicester in 1590, an amateurish drawing depicting an actor (possibly of Shakespeare as Bassanio in

The Merchant of Venice

), articles of agreement with the actor John Lowin, a âDeed of Trust' dating from 1611, and Shakespeare's exchange with the Jacobean printer William Holmes over the financial terms governing the publication of one of his plays (in the end, Shakespeare rejected Holmes's ungenerous offer: âI do esteem much my play, having taken much care writing of it ⦠Therefore I cannot in the least lower my price'). Books with Shakespeare's name and annotations were also discovered, including copies of Thomas Churchyard's

The Worthiness of Wales

, John Carion's Protestant-leaning

Chronicles

and Edmund Spenser's

The Faerie Queene

.