Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere

Read Conquering the Chaos: Win in India, Win Everywhere Online

Authors: Ravi Venkatesan

Conquering the Chaos

“India tests the capabilities of any global company to the hilt. This book tells you

what it takes to crack the India code. Great reading.”

—Jean-Pascal Tricoire, President and CEO, Schneider Electric

“A fascinating read on how to succeed in India and why it is relevant for winning

in other emerging markets. This is a must-read for all executives interested in global

growth.”

—Mukesh D. Ambani, Chairman and Managing Director, Reliance Industries

“Succeeding in emerging markets is of tremendous strategic significance for every

multinational company. If you are looking for practical advice on how to win—not just

in India, but in all emerging markets—Ravi Venkatesan’s book tells you how.”

—Nandan Nilekani, Chairman, UID Authority, Government of India; former CEO, Infosys

“

Conquering the Chaos

is a practical playbook for business success in India. Ravi Venkatesan’s hands-on

experience and extensive research will make this your go-to book for India. Even those

who are currently succeeding in India will find helpful insights here.”

—Tom Linebarger, Chairman and CEO, Cummins Inc.

“A brilliant, contrarian, and very readable manual on how to succeed in India and

other emerging markets.”

—Anand Mahindra, Chairman and Managing Director, Mahindra and Mahindra

“Ravi Venkatesan has given us the guidebook to successful growth in India we so desperately

need. He provides us with down-to-earth managerial insights that will most certainly

determine the success or failure of ventures in this critical economy. A must-read

for anyone interested in globalization, India, and the successful enterprise.”

—Leonard Schlesinger, President, Babson College; former professor, Harvard Business

School

“A brilliant book that I finished in a single sitting.”

—K. V. Kamath, Chairman, Infosys Limited; Chairman, ICICI Bank

“India is an important market for global companies and will become even more important

in the future.

Conquering the Chaos

tells you the basic do’s and don’ts of entering and managing a successful business

in India, in simple and compelling terms.”

—Tim Solso, former Chairman and CEO, Cummins; Member of the Board, General Motors

“Amazingly strong on concepts and rich in experience, Ravi Venkatesan combines deep

insights with powerful practical tools for how companies can succeed in India. Anyone

interested in understanding India and emerging markets must read this book.”

—Srikant M. Datar, Arthur Lowes Dickinson Professor of Accounting, Harvard Business

School

“A unique combination of timeliness and clarity regarding the great opportunities

and eye-watering challenges of sensibly investing and honestly doing business in India.

It can be hugely rewarding, but the challenges are indeed incredible! Ravi Venkatesan

describes them, and more, with clarity and rare honesty.”

—Ashok Ganguly, Member of Parliament, India; former Chairman, Hindustan Unilever

“

Conquering the Chaos

is a provocative and candid take on doing business in India. It should be on the

reading list of anyone interested in globalization and emerging markets.”

—Samuel R. Allen, Chairman and CEO, Deere & Company

“Ravi Venkatesan’s book is the most tough, honest, unique, solutions-based, and strategic

book on doing business in India. A must-read for all CEOs engaged with the economies

of tomorrow.”

—Tarun Das, former Director General, Confederation of Indian Industry

“Ravi Venkatesan has written an important book. It mixes real-life, insightful experience

of doing business across different industries in India with a more general explanatory

model. I believe it is a must-read for business leaders of global companies.”

—Leif Johansson, Chairman, Ericsson and Astra-Zeneca

“This is an important and insightful book for any global company wanting to build

a business in India. It has breadth, depth, and perspective, and highlights the importance

of culture and values.”

—Carl Henric Svanberg, Chairman, BP and Volvo

“While this book provides powerful insights into a complex country and culture, the

more fundamental lessons center on transformational leadership in our twenty-first-century

world.”

—Ann Fudge, former Chairman and CEO, Young & Rubicam

“Having had the pleasure of working with Ravi Venkatesan during his Microsoft years,

it’s inspiring to see the challenges he faced, his successes, and the lessons he learned

codified into knowledge that is helpful to all.

Conquering the Chaos

is both a way of getting started in India and other emerging markets and a poignant

reminder of what we must all continue to pursue as global leaders.”

—Stephen Elop, Chairman and CEO, Nokia

Copyright 2013 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Requests

for permission should be directed to

[email protected]

, or mailed to Permissions, Harvard Business School Publishing, 60 Harvard Way, Boston,

Massachusetts 02163.

The web addresses referenced in this book were live and correct at the time of the

book’s publication but may be subject to change.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Venkatesan, Ravi.

Conquering the chaos : win in India, win everywhere / Ravi Venkatesan.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4221-8430-1

1. International business enterprises—India. 2. Business enterprises, Foreign—India.

3. Corporate culture—India. 4. Joint ventures—India. I. Title.

HD2899.V38 2013

658’.0490954—dc23

2012051720

ISBN13: 978-1-4221-8430-1

eISBN: 978-1-4221-8431-8

Dedicated to honest and upright

government officials in all emerging markets

for the courage they show every day

India should be viewed less as a difficult market where strange things are happening,

and more as a market that is simply ahead of many other markets in its evolution …

If we don’t figure out how to win in India, we could end up losing in a lot of other

geographies around the world. Conversely, if we can win in India, we can win everywhere.

—STEPHEN ELOP, CEO, NOKIA

Why have only a handful of multinational companies succeeded in India, while so many

simply muddle along? What does success in India look like and what does it take to

win in India? With India recently losing much of her shine, is that even important?

Why should multinational companies bother with India’s chaos?

My interest in trying to understand whether India actually matters to most multinational

corporations stems from my experience over the past fifteen years in helping to build

two billion-dollar businesses for American companies in India, first for engine maker

Cummins Inc. and later for software giant Microsoft Inc. Both have been successful

in India. Cummins India has built a dominant 60-plus percent market share in both

the diesel engines and the diesel generating sets businesses (estimated at over 50

percent market share). It is a highly respected company. Similarly, Microsoft India

is far and away the leader in the software business in India and consistently ranks

among the best employers and most admired brands in India.

There’s one difference, though.

India contributes roughly 10 percent of Cummins’s global revenues and even more of

its profits and growth, but Microsoft derives just 1.5 percent of its global revenues

from India. More importantly, if you extrapolate their growth rates for the next ten

years, the situation won’t change much. If Microsoft grows its global revenues by

a conservative 7 percent to 10 percent over the decade, and its India business expands

at, say, 20 percent or 25 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR), by 2022, India

would still account for only about 5 percent of the company’s revenues. Its contribution

to Microsoft’s global growth would also remain modest. Thus, India matters deeply

to Cummins, but not as much to Microsoft.

Microsoft is hardly unique. Many other well-run companies such as Caterpillar, Toyota,

and Daimler face the same situation. In fact, most multinational companies see India

primarily as a talent pool for offshoring knowledge and a market that will be important

someday down the road. As a result, India typically accounts for a trivial 1 percent

or less of their global revenues and profits, and an anemic 5 percent or so of their

global growth. The Indian market’s numbers for these companies are akin to a rounding-off

error, and given their trajectories, they will still be irrelevantly small a decade

from now. Would that not have strategic consequences?

These numbers and their potential consequences bothered me.

This prompted me to spend a year interviewing the CEOs and senior leaders of around

thirty companies in different industries. I also convened meetings of some of the

most accomplished country managers in India, including the leaders of Nokia, GE, Dell,

Honeywell, Volvo, Schneider Electric, JCB, Bosch, Unilever, and Nestlé. I tested our

hypotheses with some of the global leaders to whom they report such as Honeywell’s

Shane Tedjarati, Walmart Asia’s Scott Price, Ericsson CEO Hans Vestberg, and Standard

Chartered Bank’s executive director, Jaspal Bindra.

My research and interviews led me to uncover some fundamental issues that I will tackle

in this book.

1

I will be addressing questions such as, How should senior leaders of multinational

companies think about India and other emerging markets? Why is “winning in India”

so hard? Why have some companies succeeded spectacularly in the same challenging environment?

What are the likely consequences of failing to build a strong market position in India?

My focus throughout will be on providing practical perspectives, real-world anecdotes,

and actionable takeaways for operating managers.

India appears to be at a tipping point. Global success in information technology,

a decade of growth, and some excellent public relations enabled the country to change

people’s perception of it. After decades of being equated with Pakistan, India has

increasingly come to be associated with China in terms of potential. However, the

past couple of years have been devastating. Massive corruption scandals, weak kleptocratic

political leadership, divisive politics, stalled reforms, and a decelerating economy

are making Indians and foreigners alike question the future. Gone is the hubris that

dared India to think it could do better than China or even some developed countries.

THE PLUSES.

That said, India does have many things going for it. One is the large pool of talent.

It may be getting harder and costlier to find and keep good talent, but India remains

one of the most important places in the world to do knowledge work, ranging from managing

business processes to running information technology systems, and for engineering

work ranging from drafting and testing to sophisticated design and analysis. Shifting

those processes to India has the ability to change companies’ cost structures and

add several hundred basis points to their profitability. Some, such as IBM (142,000

employees in India as of 2012), Honeywell (20,000), and Dell (28,000), have leveraged

this effectively, but others, particularly European and Japanese companies, have yet

to harness the IQ and energy of young Indians. (Offshoring and outsourcing are well

covered elsewhere, and I will not spend much time on them; my focus in this book is

the Indian market.)

The second plus is the intrinsic strength of the economy. It is difficult to ignore

the progress that India has made over the past three decades, albeit in fits and starts.

In his book,

India Grows at Night

, Gurucharan Das says that “India grows at night … when the government sleeps,” suggesting

that the country has done well despite, not because of, the state. India is a story

of private success trumping public failure.

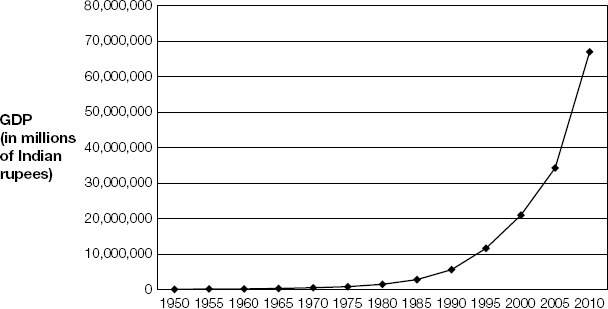

Figure 1-1

, a graph of India’s GDP growth from 1980 to 2010, illustrates this quite dramatically;

what’s impressive is the country’s sustained economic growth despite many different

governments in power, some more effective than others (see

figure 1-1

).

Several reasons account for these economic gains, such as the ambitions and drive

of India’s youthful population—the so-called demographic dividend. A healthy savings

rate as well as rising rural incomes driven by pricing support for crops, significant

improvements in literacy and education, a culture of entrepreneurship and improvisation

(although not quite innovation as it is commonly understood), a competent managerial

class, a reasonably sound banking system and capital market, and a fair and activist

Supreme Court have contributed as well.

Moreover, India has become more federal, with power shifting to the state governments

from the central government. Growth is increasingly powered by the states rather than

by policy decisions in Delhi, and the states’ economic performance, even that of perennially

backward Bihar, has been encouraging. Above all, there has been an irreversible awakening

of the aspirations of a billion people. The growth genie is out of the bottle, and

India is on an irreversible course of development.

FIGURE 1-1

Growth of India’s GDP

Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest businessman, puts it well: “India is a bottom-up not

a top-down story.” No country except China has the same medium- and long-term economic

potential as India. Even in a scenario of modest 6 percent to 7 percent GDP growth,

by 2030, the country will have the largest middle-class population and share of middle-class

consumption in the world. India’s progress has prompted frequent comparison with the

aerodynamically challenged bumblebee, which theoretically should be incapable of flight.

Yet, both continue to defy the odds.

2

THE MINUSES.

Nearly fifty years ago, John Kenneth Galbraith, the US ambassador to India and an

ardent Indophile, called India “a functioning anarchy.” In that one respect, not much

has changed. Negating the considerable intrinsic strengths of India is corrupt and

incompetent governance at all levels of the nation: central, state, city, and village.

Nearly 25 percent of the members of India’s lower house of Parliament have had criminal

cases filed against them, ranging from kidnapping and murder to extortion and robbery.

Unbounded greed and corruption have resulted in politicians, bureaucrats, and businesspeople

becoming predatory to an extent seen only in some African dictatorships and the post–Soviet

Union era in Russia. Well-connected industrialists, politicians, and public officials

have conspired to carve up India’s natural resources, ranging from mineral resources

to land and the telecom spectrum.

However, the system of patronage and crony capitalism has been paralyzed, as its workings

stand exposed by a mixture of fearless activists, Supreme Court interventions, government

audits, a feisty media, and the public itself, angry over graft and drift. Scarcely

a month goes by without the exposure of yet another scandal, such as the 2G telecom

scandal in 2010, which

Time

dubbed the second-biggest scandal after Watergate.

3

Other scandals have since come to light in the power and mining sectors, as well

as several land deals.

4

Corruption in India isn’t limited to crony capitalism. Graft has permeated the fabric

of Indian society, and at every step, officials harass individuals and companies,

whether it is to register a land transaction, renew a multitude of licenses, clear

a shipment through customs, or win a public tender. Companies find themselves continuously

extorted by inspectors who handle pollution control, labor laws, and indirect taxes,

and they must comply with arcane regulations dating back a century or more. Their

choice is between spending countless hours defending themselves or paying one more

tax to individuals so they can focus on business.

The ineptness of the government in driving essential policy reforms has also become

legendary. Maimed by arrogance and corruption scandals, a coalition government, led

by the Congress Party, has struggled in recent times to pass unpopular measures because

of opposition from coalition partners and political rivals. For example, the government

tried to open up the retail sector to foreign investment in 2011, only to reverse

itself because of the opposition of its political allies. In December 2012, a frustrated

but determined prime minister finally used all his political capital to push the measure

through Parliament, but left the final decision to each state. Global retailers must

negotiate licenses with each state they wish to enter.

Acquiring land remains tricky, and obtaining environmental clearances can take years.

According to G. V. K. Reddy, whose company was responsible for the recent overhaul

of Mumbai’s airport, the developer had to deal with over 220 cases over property,

environmental, and labor disputes in the process. Creating a one-stop shop for project

approvals and unifying regulations across state borders would smooth the road for

developers. However, India’s land acquisition law has not been modified since 1894,

and Parliament has held up a new law for months, as lawmakers struggle to find the

middle ground between industrial development and defending the rights of small landowners.

For these and other reasons, critical infrastructure projects have been delayed. Despite

the government’s ambitious aims of attracting $1 trillion in infrastructure investments,

India is littered with stalled projects while Indians endure pothole-filled and garbage-laden

roads, congested ports and airports, creaky railways, overflowing drains, and the

absence of clean drinking water. Power plants stand idle, crippled by shortages of

fuel, while 600 million Indians were stranded without power for two days in July 2012

and the citizens of the southern state of Tamil Nadu endure daily power outages lasting

twelve hours or more. The list of woes when it comes to infrastructure is endless.

A final issue, one that has become a Frankenstein monster, is taxation. Not only is

the tax regime complex and deliberately ambiguous, but to fund the massive fiscal

deficit caused by unsustainable welfare programs, the revenue authorities have collection

targets. They have unprecedented discretionary powers, which they wield like a blunt

weapon. All companies face harassment, but multinational companies make particularly

easy targets, as companies like Vodafone, HP, Shell, Nokia, Microsoft, and Nestlé

will attest. The most dramatic example is the bruising dispute between the finance

ministry and Vodafone, India’s largest foreign investor, over a disputed $2 billion

capital gains tax bill. To get around a Supreme Court ruling in Vodafone’s favor,

the finance ministry wanted to amend the law retroactively to April 1962! Whatever

the final outcome, the incident has dented India’s image in the eyes of investors

everywhere, while raising serious concerns among business leaders and governments.

A key economic adviser to the prime minister comments: “A government that changes

the law retrospectively at will to fit its interpretation introduces tremendous uncertainty

into business decisions, and it sets itself outside the law. India has missed an excellent

opportunity to show its respect for the rule of law even if it believes the law is

poorly written. That is far more damaging than any tax revenues it could obtain by

being capricious.”

5

The Vodafone case, the harassment of respected companies and professionals, and the

proposed General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR), an ambiguous attempt to prevent tax

evasion, are creating uncertainty, anger, and anxiety at a time when the government

desperately needs to attract more foreign investment. One CEO of a multinational,

who asked not to be named, says the unpredictability of the tax regime puts India

at par with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, adding that it is contradictory

when the Indian government says it needs foreign investments but creates investor-unfriendly

policies at the same time.

All these factors have together made India one of the most challenging countries in

which to operate. Ratan Tata, the chairperson of the Tata Group, cautioned that if

the government didn’t step in and uphold the rule of law, “there was every possibility

that India could become a banana republic.”

6

Sunil Mittal, the highly influential and cautious chairperson of telecom operator

Bharti Airtel, didn’t mince his words either: “This has been the most destructive

period of regulatory environment I have seen in 16 years,” he publicly stated in May

2012.

7

The numbers bear him out. According to the World Bank, India ranks 133 of 183 countries

in terms of ease of doing business (falling from 120 in 2007), 169 in terms of taxation,

and, despite the public outrage against corruption, matters may be getting worse as

India sank 11 places to number 95 in 2011. The Indian economy has slowed to a new

Hindu rate of growth of 5 percent compared with the earlier 3 percent.

8

Given the realities of dynastic rule and coalition politics, confidence in the government’s

abilities to tackle the enormous challenges is low. Ramachandra Guha, a historian

and writer on Indian affairs, argues that instability may be India’s destiny. He says

that bad politics, corrupt leaders, and weak and politicized institutions mean that

instability and policy incoherence may be a long-term feature.

9

Indian companies may have no choice but to operate in the country, but multinational

companies do. Dave Cote, chairperson and CEO of Honeywell, a company with twenty thousand

employees in India and an ardent advocate of the country, recently told the

Wall Street Journal

: “Foreign companies are starting to become scared here [in India]. I worry that the

Indian bureaucracy is becoming stultifying. I will hire people here, but I will be

a lot more reticent about investing in India.”

10

Cote’s dismay reflects the growing sentiment among global business leaders, who are

increasingly disillusioned and pessimistic about India’s prospects and rapidly prioritizing

investments elsewhere.

It would therefore be logical to conclude that global businesses shouldn’t bother

with India, at least not in the short run. Or is there something that multinational

corporations are missing by jumping to that conclusion?