Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist (37 page)

Read Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist Online

Authors: Patrick Moore

Shortly before he died, Bob Hunter offered me a prolific apology over a few glasses of wine in my kitchen in Vancouver. This was witnessed by my wife, Eileen, and by my eco-warrior buddy, Rex Weyler. Bob realized that he had made the mistake of attacking the person rather than debating the issue

. My rule-put family and friends above politics

.

None of this daunted me. I was determined to do what I knew was right. I really had no choice. I either caved in to people who I did not agree with or I followed my conscience. I knew it would be a long struggle because so many environmentalists, and so many people who lived in cities, had already made up their minds on the subject. Indeed nearly 10 years would pass before I could claim to be vindicated in my beliefs. During those 10 years, from the early 1990s to the early 2000s, I endured attack after attack, usually in the form of name-calling. The media made a willing conduit for this style of assault, repeating the “eco-Judas” slur time after time. If I thought I had developed a thick skin during my time with Greenpeace, that was nothing compared to the hide I developed during these years. It culminated in 1996 with the launch of the “Patrick Moore is a Big Fat Liar” website by the Forest Action Network, a band of anti-forestry campaigners who thought nothing of using misinformation and distortion to further their cause. They published what they claimed to be my “Ten Top Lies.” Realizing it is possible to get away with saying nearly anything on the Internet, I seriously considered suing for libel but then, instead, published “Patrick Moore is Not a Big Fat Liar” on my own website.

[5]

Over the years people who read the material on both websites get a pretty good idea of my position. So in a way the name-callers did me a favor. It’s always gratifying when you can use your critics words to your own advantage.

In retrospect the anti-forestry campaign was the beginning of a trend in the environmental movement that targets the people who produce the material, food, and energy for all of us. This pits the vast number of people who live in urban environments against the very people who work hard in the country to provide the essentials of civilized life. It is a modern version of Aesop’s Fable “The City Mouse and the Country Mouse,” only today the city mice are in a huge majority and control the major media outlets. They can usually drown out the protestations of loggers, farmers, miners, energy producers, and fisher folk. They bite the hand that feeds them. It is time to change that pattern and to give the people who do the hard work in the hot sun and driving rain their due.

On a dark and rainy morning in December 1992, Eileen and I were awakened by a crashing sound outside our front door. Upon going downstairs to investigate Eileen hollered up that I had better come down and take a look. Someone had dumped eight giant garbage bags of horse manure on our front porch and steps. A note was left with “Tree Killer” scribbled on it. It wasn’t a pretty sight or smell.

Eileen did not want the embarrassment of our neighbors noticing 400 pounds of horse crap on our porch. I quickly dressed and went out into the torrential downpour, grabbed a shovel and the wheelbarrow, and spread all the manure over our front and back flower beds before daylight. The next spring and summer our garden was more beautiful with blooms than it had ever been. Embarrassment was avoided, and talk about making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear!

In 1995, nearly 10 years after I left Greenpeace, an event occurred that made it even clearer I had made the right choice in leaving the group. Shell Oil was granted permission by the British environment ministry to dispose of the North Sea oil storage platform, Brent Spar, in deep water in the North Atlantic Ocean. Greenpeace immediately accused Shell of using the sea as a “dustbin.” Greenpeace campaigners maintained that there were hundreds of tonnes of petroleum wastes on board the Brent Spar and that some of these were radioactive. They organized a consumer boycott of Shell and the company’s service stations were fire-bombed in Germany. The boycott cost the company millions in sales. Then German chancellor Helmut Kohl denounced the British government’s decision to allow the dumping. Caught completely off guard, Shell ordered the tug that was already towing the rig to its burial site to turn back. They then announced they had abandoned the plan for deep-sea disposal. This embarrassed Britain’s prime minister, John Major.

An independent investigation subsequently revealed that the rig had been properly cleaned and did not contain the toxic or radioactive waste Greenpeace claimed it did. Greenpeace wrote to Shell apologizing for the factual error. But the group did not change its position on deep-sea disposal despite the fact that on-land disposal would cause far greater environmental impact.

During all the public outrage directed against Shell for daring to sink a large piece of steel and concrete, it was never noted that Greenpeace had purposely sunk its own ship off the coast of New Zealand in 1986. When the French government bombed and sank the

Rainbow Warrior

in Auckland Harbour in 1985, the vessel was permanently disabled. It was later refloated, patched up, cleaned, and towed to a marine park, where it was sunk in shallow water as a dive site. Greenpeace said the ship would be an artificial reef and would support increased marine life.

The Brent Spar and the

Rainbow Warrior

are in no way fundamentally different from each other. The sinking of the Brent Spar could also be rationalized as providing habitat for marine creatures. It’s just that the public relations people at Shell were not as clever as those at Greenpeace. And in this case Greenpeace got away with using misinformation even though it had to admit its error after the fact. After spending tens of millions of dollars on studies, Shell announced that it had abandoned any plan for deep-sea disposal and supported a proposal to reuse the rig as pylons in a dock extension project in Norway. Tens of millions of dollars and much precious time wasted over an issue that had nothing to do with the environment and everything to do with misinformation, misguided priorities, and fundraising hysteria.

To make matters worse, in 1998 Greenpeace successfully campaigned for a ban on all marine disposal of disused oil installations. This will result in hundreds of millions, even billions of dollars, in unnecessary costs. Many of these rigs and their components cannot be recycled in a cost-effective manner. One obvious solution would be to designate an area in the North Sea, away from shipping lanes, for the creation of a large artificial reef and to sink obsolete oil rigs there after cleaning them. This would provide a breeding area for fish and other marine life, enhancing the biological and economic productivity of the sea. But Greenpeace isn’t looking for solutions, only conflicts and bad guys.

[1]

. Roger Fisher and William Ury,

Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In

(New York: Penguin Books, 1983).

[2]

. Patrick Moore, “From Confrontation to Consensus,” April 1998, http://www.greenspirit.com/key_issues.cfm?msid=32

[3]

. Patrick Moore, “Are All Carbon Atoms Created Equal?” October 19, 1991,

http://www.beattystreetpublishing.com/confessions/references/are-carbon-atoms-equal

[4]

. Nigel Dudley, “Forests in Trouble: A Review of the Status of Temperate Forests Worldwide,” WWF International, September 2002, http://www.equilibriumresearch.com/upload/document/forestsintroubleexsum.pdf

[5]

. Patrick Moore, “Patrick Moore is Not a Big Fat Liar,” 1996, http://www.greenspirit.com/logbook.cfm?msid=44

Chapter 14 -

Trees Are The Answer

You may ask, If trees are the answer, then what is the question? I believe trees are the answer to many questions about the future of human civilization and the preservation of the environment. Questions like, “What is the most environmentally friendly material for home construction?” “How can we pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and how can we offset the greenhouse gas emissions caused by our excessive use of fossil fuels?” “How can we build healthy soils and keep our air and water clean?” “How can we provide more habitat for wildlife and biodiversity?” “How can we increase literacy and provide sanitary tissue products in developing countries?” “How can we make this earth more green and beautiful?” The answer to all these questions and more is “trees.” From the most practical question of what to build a house with to the most aesthetic issue of how to make the world prettier, trees provide an obvious solution. In other words I am a tree-hugging, tree-planting, tree-cutting fanatic. Trees show us there can be more than one answer to a question, and sometimes the answers seem to contradict one another. But I hope to demonstrate that just because we love trees and recognize their environmental value doesn’t mean we shouldn’t use them for our own needs.

Forests, and the trees that define them, are the most complex systems we know of in the universe. To a computer scientist or a molecular biologist, this statement may at first seem exaggerated, but it is a fact. To begin with, we don’t know of any other planet that harbors life. On Earth it is undeniable that forested ecosystems are home to the vast majority of living species. Every needle and leaf on every tree is a factory more complex than the most sophisticated chemical plant or nuclear reactor. We may be capable of genetic modification and producing atomic energy but we can’t imitate photosynthesis, never mind the infinitely more intricate systems that make up the entirety of a forest. There is every reason, despite our considerable talents, to live in wonder of the natural world and, I would argue, of forests in particular. As far as we are concerned, photosynthesis might just as well be magic.

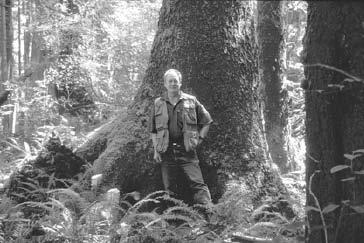

Me posing in front of a 100-year-old second-growth Sitka spruce tree on our land in Winter Harbour. You have to live in the rain forest for half a lifetime to appreciate the cycles of disturbance and growth.

Our species was born of the forest, descended from primates that came down from trees to the savannah, got this two-legged habit of mobility and made history. The males among us excelled at running across the open plains, spears and clubs in hand, replacing even the lion as “king of the beasts.” But in our new posture the forest was no longer our primary home. The forest was more dangerous than the savannah because predators could find cover there and make a surprise attack. We evolved from a forest-dependent species to a species that distrusted and disliked the forest. Then we learned to use fire. The forest provided the firewood and when we used fire to clear the forest we made more productive grazing land for the animals we hunted for food, bone, sinew, and hide. Then we invented the axe.

If you observe the dwellings of people who live in Africa and other tropical regions today, you will see they keep vegetation away from their huts. A couple of million years of experience with snakes, scorpions, and lions has resulted in a scorched earth approach to yard maintenance. As humans spread out across the other continents, they took with them the habit of making large clearings around their homes. In colder climates this has the added benefit of letting the sunshine in. Trees provided the building materials for shelter and the fuel to keep the homes warm. When we began the transformation from hunting and gathering to agriculture, the axes really came in handy. The forest was an obstacle to be overcome. Over the past 10,000 years we have converted nearly one-third of the world’s forests into cities, farms, and pastures, the best one-third in terms of fertility and productivity. Thus our species became a dominant force in shaping landscapes to our own design. No wonder we became too sure of our ability to overcome all natural obstacles as we transformed the earth to serve our growing needs for food, energy, and materials.

As long as the human population was reasonably small compared with the vastness of global forests, deforestation remained a very local issue. But as numbers grew and more land was cleared for crops and grazing animals, we began to take our toll on the natural world. It went reasonably well, other than the frequent wars and short lifespan, until the Industrial Revolution and the exponential increase in the use of wood for fuel, fuel for heating, fuel for smelting iron and copper, fuel for glassworks, and eventually fuel for steam engines to run the factories, ships, and trains. During the 18th and 19th centuries forests of the industrialized European countries were rapidly decimated and wood soon came into short supply.

[1]