Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist (16 page)

Read Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist Online

Authors: Patrick Moore

We kept it a secret, partly because we didn’t want to let on that the U.S. was giving us the Soviet coordinates, but was not willing to give the Japanese whalers’ positions. We didn’t want to be seen as favoring the American ally and picking on the Cold War opponent because we wanted to be neutral in the political sense. This was not easy because interests in the U.S. administration wanted to use us to promote anti-Soviet agendas. Other interests, also mainly in the U.S., sought to portray the Japanese whalers in a racist light, harkening back to Pearl Harbor. It wasn’t easy to avoid political and nationalistic elements in the whale wars.

In early July we confronted the whaling fleet 1400 miles southwest of San Francisco, off Baja California. With our new ship we could stay with the whalers and we were able to successfully interfere with their hunting, reducing the number of whales they killed. The film footage we obtained was broadcast around the world again. We were definitely gaining momentum.

We were no ordinary cruise ship or freighter, so we could do things our own way. When we weren’t in the thick of battle, one of those things included going for a daily swim in the deep blue waters of the warm Pacific. It was about 6,000 feet deep and populated by flying fish, blue sharks, and sunfish. We would stop the ship at around noon and up to a dozen of us who were not afraid of 6,000 feet of water would leap off the deck while Captain Korotva stood on the flying bridge with a rifle in case he needed to shoot sharks. We were more concerned that he would hit us and wished he would put the gun away.

One day, as we came to a stop for our daily dip, there happened to be a very large sunfish alongside the

James Bay

. It was about six feet long and deep. If you haven’t seen a sunfish before, it is a wondrous thing to behold. They are as deep as they are long and quite thin through the middle; in other words they are shaped like a discus, hence the reference to the sun. They have a mouth with no teeth that opens about two inches wide. Their main food is plankton and jellyfish, which they ingest as they move along. The sunfish has a couple of tiny fins and a small tail and a top speed of about two knots, so it could not outswim a human, never mind a shark or other predator. That is why they are composed of not much more than thick skin and bone, so no predator would ever consider trying to eat them. Because they swim slowly, they become a host to various barnacles and algae that attach themselves to the rear and bottom of the fish. In addition they are accompanied by gleaner fish, which wait for bits of food that get past the sunfish’s mouth. They are very much like a floating reef, supporting many other species in a commensural relationship as they ply the surface waters.

[1]

It was an entire marine ecosystem around a single fish.

There were only six of us on this swim, one of whom was the lovely Caroline Keddy, who had joined us in San Francisco. In snorkel gear, most of us approached the sunfish with some trepidation, as it was much larger than we were. Caroline was not even slightly afraid and moved right in alongside the giant fish. Perhaps it was because she was a hippy from the Bay and had never encountered a wild animal before. Soon she was touching the sunfish on the face and rubbing its back. The sunfish was obviously pleased with her attentions as it sidled up to her, making no effort to escape. Seeing this the rest of us joined in the love fest, taking turns petting the fish and observing the many species attached to it or following along. But it was clear the sunfish favored Caroline, perhaps because she was the first to make contact, or because the rest of us were not so attractive.

We lost track of time but eventually George blew the ship’s whistle for us to come back aboard. By now we had drifted about 300 feet away from the ship, so it was a bit of a swim back home. Caroline held back a minute to say goodbye to her sunfish and then joined us as we headed to the

James Bay

. No sooner had we begun our return than the sunfish turned and with all its two knots of top speed started to follow us. But the fish wasn’t just following us; it was following Caroline. As she emerged from the ocean to climb the rope ladder hanging down the side of the ship, the sunfish looked up at her with its big eyes as if to say “Farewell, I love you.” I am not a sappy romantic by any stretch of the imagination, but this was a very moving event. We marked the chart with the location where a sunfish fell in love with a human being in 6,000 feet of water in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, on July 12, 1977.

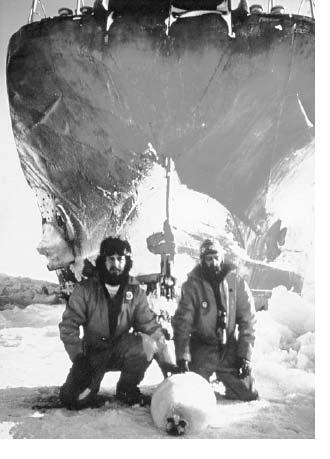

Paul Watson and Bob Hunter pose with a baby harp seal after they stopped the icebreaking sealing ship in its tracks—probably a Guinness Book of Records first. Photo: Patrick Moore

Back on task, we followed the Soviet fleet across the Pacific to Hawaii, dogging them all the way. We decided to pull in to Lahaina on Maui, where there was a good group of whale-saving supporters, as Lahaina is a major center for viewing humpback whales in the winter months. We were determined to try to find the Japanese whaling fleet so that we could provide a balance to our focus on the Russians. Reports indicated it was operating just west of the Hawaiian Islands. The U.S. Coast Guard offered to take us up in one of their surveillance planes on a routine mission to see if we could find the fleet. We decided we would move the

James Bay

to Nawiliwili Harbor on Kauai as we would be closer to the fleet if they found it.

By this time the strain of the voyage was coming to the surface. On our previous expeditions aboard the

Phyllis Cormack

there were only 12 crew members; the

James Bay

‘s crew numbered 32. We were living in cramped quarters and we were a pretty headstrong bunch. The fact that two of the couples on board had broken up coincidentally and that they were now involved in new relationships, which left jealous exes with shattered hearts and nerves, was complicating personal relations. This is bad enough on land where people can get away from one another. On a ship it is positively suicidal. This behavior was, of course, entirely contrary to standing orders. As a member of the crew selection committee, I had made it clear that if you came on board as a single person you went off single and that if you came on with a partner you left with the same one. But it is not always possible to control affairs of the heart, even on a voyage to save the whales.

Working seven days a week, we built bunks and galleys for 32 crew members in what had been an empty shell of a ship. By the time we set sail the M.V.

James Bay

was nicely equipped. Photo: Rex Weyler

The morning of July 30 began well with reports of a school of dolphins in the outer harbor. We launched our three Zodiacs and sped out to see them. We found at least 50 Pacific white-sided dolphins in the pod and they came leaping toward us and then followed us along for miles. You could literally reach out and touch them as they surfaced right next to the Zodiacs, making rainbows in the spray. It was a magical experience.

I guess some of the guys needed to let off steam as George, Bob, and Mel had begun to drink straight vodka from the bottle at ten in the morning. They were hooting and hollering among the dolphins when Bob decided to go for a swim off the Zodiac. He picked a bad spot, as he dived into the ocean amid a large coral head. By the time George pulled him into the boat, he was badly lacerated from been dragged back and forth over the coral by the surf. It appeared he had lost a considerable amount of skin.

This put a damper on the morning’s fun as we rushed Bob back to the boat for medical treatment. Paul Watson’s partner, Marilyn Kaga, was the ship’s nurse, so Bob was delivered into her hands, by this time in considerable pain. Mistaking a bottle of rubbing alcohol for hydrogen peroxide, nurse Marilyn poured it all over Bob’s wounds causing him to go into a catatonic fit of pain. Captain George and Paul got into a shouting match, which ended with George punching Paul in the head: so much for the peace in Greenpeace. As Bob’s eyes rolled back into his sockets, we carried him to his bunk, where he screamed for a very long time and refused to be treated for some hours. Eventually we got some antiseptic cream on his cuts and scrapes and settled him down.

The pride of the Greenpeace Pacific fleet, the

James Bay

, on its first voyage to save the whales, joined by the

Phyllis Cormack

for its second whale campaign against Russian and Japanese whalers. This photo was taken in June 1976 in Sydney, B.C., at the outset of the voyage. photo: Matt Heron

With our illustrious leader Bob down for the count, Paul Watson decided to lead a mutiny of the crew. Marilyn’s mistake and his beating from the captain embarrassed him. As the rebellion unfolded in the crew’s quarters, George and Mel went back out in a Zodiac with their bottle(s) of vodka. By nightfall, they were raging drunk and decided to go to the little discotheque at the end of the pier. Realizing they would never get past the bouncers, they decided to scale the pier up the pilings from the water. We watched as various patrons repelled them with chairs until they retreated to their boat. Later in the evening they managed to ram and hole a small dinghy tied behind a nice sailboat that was at anchor in the harbor. As the dinghy was sinking, Mel leaped into it with a bailing can only to go down with the ship.

Things settled down by midnight, but we knew we had to get out of town before daybreak. We cast off at four in the morning and headed back to Lahaina, where our reputation was not so sullied and waited for word of the Japanese fleet. We made a sincere effort, but after two weeks we gave up on the Japanese, and after reprovisioning in Kahalui we headed back for the Soviet fleet, reported by our shore station in San Francisco to be 1200 miles north of Hawaii. This location is about as far as you can get from land anywhere in the Northern Hemisphere. The weather changed from tropical to temperamental as we entered the Pacific Gyre, where currents circle, keeping flotsam in their grip for hundreds of years. The Russian whaling fleet appeared before us in a misty-grey sea.

As we had done a few dozen times before, we launched two Zodiacs, this time into unusually rough seas. Paul Spong and I were the operators, with Fred Easton on film and Rex Weyler on stills. We no sooner got alongside a harpoon boat than the fog set in, obscuring our mother ship that was now about three miles distant. We decided to stay with the whaler and this was our mistake. Within 15 minutes we had completely lost our bearings, the fog had become thicker, and we were realizing we only had an hour of daylight to get back to the

James Bay

. In addition we had left our ship in the sunshine with light clothing, no survival suits, no radar reflectors, and no food. Some eco-navy.