Conceived in Liberty (172 page)

Read Conceived in Liberty Online

Authors: Murray N. Rothbard

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

Samuel Adams

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

John Adams

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

1774 Caricature of the Bostonians Paying the Excise Man or Tarring and Feathering

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

Patrick Henry

(Known as the Aylett portrait)

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

John Hancock

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

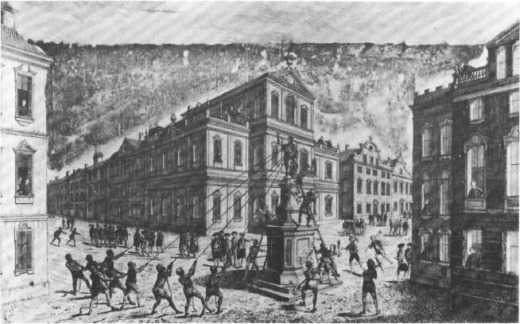

Peep-show Print of the Destruction of the Statue of George III in New York

ROCKINGHAM.

2

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

Woodcut of the Marquis of Rockingham

Courtesy of The New-York Historical Society, New York City

.

The Boston Massacre

(Drawn, engraved, printed, and sold by Paul Revere)

The Townshend Crisis, 1766—1770

35

The Mutiny Act

Though the Stamp Act crisis was over, an important irritant in Anglo-American relations remained. During 1765, Grenville had passed the Mutiny Act, which gave the British army the right to quarter its troops in private American dwellings. Originally the troops were to be quartered in private homes, but the final bill, which Benjamin Franklin helped to draw up, limited houses open to seizure to inns, unoccupied buildings, and barns. The act also forced the colonial governments to furnish the soldiers with specified supplies.

*

The object of the Mutiny Act was to conscript the houses of the colonists so as to allow large bodies of British troops to be stationed in the seaports. Since any possible enemies of the colonists were on the frontiers, the purpose of quartering troops in the seaports could only be to intimidate and coerce the colonists. For this “service” the colonists would be forced to yield their dwellings to the redcoats!

During the Stamp Act crisis the Mutiny Act was forgotten and went unenforced, but after repeal of the stamp tax problems under the act came to the fore. Aside from the threat inherent in quartering the British troops, many colonists realized that the coercing of supplies was a tax in kind every bit as bad in principle as any tax levied in money. Was this new tax in kind to perform the work of the hated stamp tax—to compel the Americans to pay for British troops amongst them?

The earliest and most important resistance took place in New York, the

headquarters for the British army and its commander in chief, General Thomas Gage. New York refused to obey Gage’s request for supplies under the Mutiny Act, and insisted on complying only partially with royal requisitions while demanding that England recompense the colony. Other colonies hedged on following suit. Most did not comply fully but did not challenge the law as openly, and voted some supplies. Understandably, there was, so soon after the vigorous resistance to the Stamp Act, a general desire for respite. Notwithstanding, when the Massachusetts Council voted supplies and quarters to a British artillery troop, its action was met by a storm of denunciation from James Otis and the Assembly, and Sam Adams asked whether the Mutiny Act “is not taxing the colonies as effectually as the Stamp Act.” Otis called for a purge of the Council, and the Assembly refused to vote supplies, but in the end it voted for partial compliance.

Partial noncompliance also occurred in New Jersey. There the Assembly denounced the Mutiny Act as being “as Much an Act for laying taxes on the inhabitants as the Stamp Act,” but then voted funds. However, it officially evaded full compliance by vaguely instructing a new set of commissioners to act according to the custom of the province. South Carolina partially complied, but refused to include such specified supplies as salt and beer in its requisition. Apart from New York, the most principled resistance occurred in an unlikely—because generally the least revolutionary—colony, Georgia. Georgia demurred on even partial compliance until its 1767–68 session, when it followed the course of its neighboring sister colony, South Carolina.

To the new Tory administration in England, this partial defiance of the Mutiny Act was a red flag to the English bull. Now English troops as well as Parliament were being defied! The new prime minister, a supposed friend of American Liberty, William Pitt—now the Earl of Chatham—lost no time in displaying his true feelings toward the colonies. Bolstering Pitt’s anger toward Americans was a petition of 240 New York merchants, in late 1766, asking for free trade and for the virtual removal of the restrictive trade and navigation laws. Arch-mercantilist and imperialist that he was, Pitt responded by inducing Parliament, in the Restraining Act of June 1767, to suspend the New York Assembly completely until it was brought to heel, and complied with the Mutiny Act.

Other British Tories ranted and raved even more aggressively than Pitt. Grenville was hailed in Parliament as a prophet of the dangers of appeasement. The Duke of Bedford and his clique shouted for more regiments to be sent to teach the New Yorkers a lesson.

William Pitt had scarcely assumed the ministry, however, when his chronically intermittent insanity took hold, and he lost

de facto

control over the course of the English government. Stepping into virtual power was a flashy playboy-opportunist and unstable epileptic, the renegade Whig Charles (“Champagne Charlie”) Townshend, chancellor of the Exchequer in the Pitt

cabinet. This embodiment of opportunism, who had opposed repeal of the Stamp Act, soon decided upon a tough imperialist line toward the colonies. Part of this line was the crackdown on the New York Assembly. Here Townshend pursued a far shrewder course, for example, than Bedford, who wanted to send a military force to crush the resistant colonies. Townshend saw that this could only unite the colonies once again into another and perhaps successful rebellion; if, on the other hand, one colony alone were singled out for suppression, then would not the other colonies be too shortsighted to rally round? New York, as the most important and most defiant colony on the mutiny issue, was the obvious focal point.

In making his move, Townshend decided on suspension of the Assembly rather than outright military action. He was backed by Pitt, Grafton, Camden, and Shelburne. In the cabinet only the redoubtable liberal General Conway opposed the measure as coercion of the Americans.

The potential crisis over New York was eased when, at the same time that Britain was cracking down, the Assembly itself was deciding to surrender. Over the opposition of the radicals and by only a single vote, the Assembly decided to comply fully with the Mutiny Act. Parliament’s order for suspension never had to be enforced. New York capitulated easily, and with it the bulk of American resistance to the Mutiny Act.

One reason for New York’s flagging courage was the failure of two of its neighboring colonies, Connecticut and Pennsylvania, to give it any support. Connecticut, indeed, quartered the troops that New York had refused to supply.