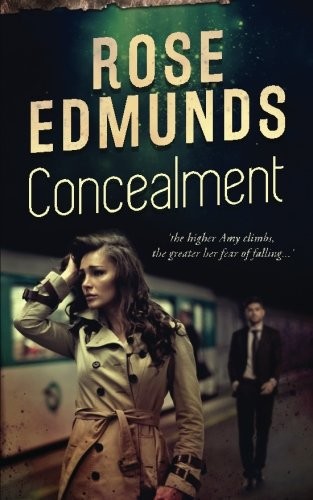

Concealment

By

Rose Edmunds

© Rose Edmunds 2015

The right of Rose Edmunds to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the author. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real people, alive or dead, is purely coincidental.

Paperback formatting by Clare Davidson

www.claredavidson.com

e-book formatting by

www.ebookpartnership.com

cover design by Ana Grigoriu

www.books-design.com

In memory of my sister Bryony, who deserved better

1

There were too many brown-noses on the Blue Skies Brainstorming Group for any good to come of it.

New boss Ed Smithies chaired the meeting. He was a pudgy, oily man with sinister white teeth, and a grating nasal whine of a voice. Few participants spoke, let alone challenged him. Instead, the gutless toadies dutifully transcribed his bombastic droning with their Pearson Malone plastic pens.

I’d been flattered when they asked me to join—it meant I was passing as normal. But an hour into the opening session, the urge to pass as normal was waning fast.

Smithies wittered on about diversity, though we already employed opportunistic robots of every imaginable colour, religion or sexual orientation.

‘

And you’re one of them.

’

I jumped at the eerily familiar female voice, which came from by the window. Everyone else carried on, oblivious.

‘

Go on—prove you’re not—tell them what idiots they are.’

Not a wise idea

, I thought,

whoever the heck you are

. And yet the suggestion was strangely appealing.

‘

You do realise playing safe might be a high-risk option.’

Yes—I’d felt that lately—not high risk for my career, you understand, but somehow high risk for me, as an individual.

‘Look, you guys,’ I said, succumbing to temptation. ‘Diversity doesn’t mean filling every job vacancy with a black lesbian in a wheelchair. It’s not some box-ticking formulaic exercise—it’s about people.’

A torpid wasp buzzed round the curled-up remnants of the sandwiches, breaking the silence as everyone waited on Smithies for their cue.

‘Does anyone else find that comment offensive?’ he asked, wrinkling his nose in disdain.

The puppets bobbed their heads in unison.

‘

That’s bonkers—how can you hire disabled black lesbians if you’re not allowed to mention them?’

An excellent point.

‘I think Amy meant to say diversity isn’t necessarily visible. You can’t always see why someone is different.’

This trite observation came from Isabelle Edwards, the most junior committee member. She was a doll-like blonde who’d captained the women’s hockey team at Oxford and still emerged with a double first. Who asked this little upstart with her flawless French manicure and prissy pearl drop earrings to act as my unofficial interpreter? If I’d meant that, I’d have said it. I was, after all, the world’s leading expert on appearing the same and being different.

‘Egg-zackly,’ said Smithies. He gave Isabelle an appreciative little glance. ‘Although why Amy couldn’t have expressed herself less provocatively…’

He broke off, as his bleak lizard eyes fixed on me, penetrating through the bravado to the quaking mess within. The invisible speaker cast her shadow onto the board table and then retreated.

And that was the moment, before Isabelle was even dead, when I peered down into the abyss and realised I was running on thin air.

No way would I let Smithies spook me again—he might be the boss, but I was no underdog. More than a hundred people reported to me as head of the Entrepreneurs Tax Advisory Group, and you don’t end up in a job like that by being a pushover.

Mind you, Smithies was no patsy either. Since moving from the Manchester office two years before, he’d systematically clawed his way into the role of Head of London Tax. Already, his “decisive management style” stood out in sharp relief against the non-interventionist approach of his predecessor, John Venner. And I knew, as you always do, that my intense and visceral loathing of him was reciprocated.

A week later we sat in Rules, ostensibly to discuss the staff pay review over lunch. The place was full of paunchy, grey-suited men guzzling hearty meat pies and rotting game birds. As I’d specifically asked my secretary to tell him I didn’t eat red meat, I could only interpret Smithies’ choice of venue as a hostile act. But perhaps I was being oversensitive.

Plaice fillet.

‘You can’t come here and eat fish,’ he said, appalled, before ordering roast rack of lamb for himself.

‘If it’s on the menu, I can have it.’

‘Any starter?’

‘Not for me.’

‘Me neither. But I think I might stretch to a glass of wine—how about you?’

I waved aside this miserly token of his esteem—Venner would have ordered a bottle.

‘Water for me, thanks.’

‘Very wise,’ he said, ‘to keep the booze under control.’

Smithies made a ridiculous show of asking for tap water. On the face of it, his reluctance to part with three pounds fifty for a bottle jarred with the Savile Row suit and Rolex watch, particularly as he would charge lunch to the firm. But this was an exercise in domination rather than frugality.

‘Certainly, sir,’ said the waiter. His gaze met mine for an instant—the knowing contemplation of a man who was likely writing a PhD thesis on Wittgenstein when he wasn’t waiting tables.

Now Smithies directed his attention towards me.

‘So tell me, Amy,’ he said, flashing his flawless teeth in a reptilian grin, ‘are you destabilised by the management changes?’

They say never smile at a crocodile. But it’s hard not to when it smiles at you.

‘Why, of course not,’ I assured him. ‘Should I be?’

Smithies’ predecessor had left in a hurry to join the board of a client, amid rumours he’d been caught downloading child porn on his computer. You work closely with someone for years and think you know him well, but sometimes you’re mistaken—so his departure was surprising, but hardly destabilising.

‘You seemed on edge in the meeting last week.’

‘No, not at all.’

‘Well, you know what they say—perception is reality.’

‘But everyone’s perception is different isn’t it?’ I countered, perhaps unwisely.

‘Egg-zackly. And so when several independent people have the same impression, it’s liable to be correct.’

Therein lay the power of this stale leadership maxim. Someone important formed a negative view, others “independently” followed, and it quickly became established as the truth.

‘And while we’re on the subject of perception,’ he added, ‘I’m afraid we’ll have to let you go from the Blue Skies committee. A number of people complained to me afterwards about your inappropriate comment.’

The number was almost certainly zero, but I didn’t care anyway.

‘Fine with me.’

So far, I’d handled him with ease.

‘Now, I

am

a bit tight on time,’ I told him, consulting my watch. It was an Omega not Rolex, but then my profit share was less than half Smithies’. ‘So shall we get down to the main business?’

But Smithies was reluctant to abandon his attempts to unnerve me.

‘Yes, but naturally, it goes without saying that if you ever feel unduly stressed by things, just say the word...’

His fake avuncular concern grated as much as the tenor of his voice—after all, at forty he was only two years older than me.

‘I’m perfectly OK, thanks.’

He held my gaze for a moment, probing the turmoil inside. But that only stiffened my determination—he couldn’t see, he couldn’t know the insecurity that plagued me. Sure, pretending to be normal was tough sometimes, especially when you had no clue what normal meant, but I’d done a pretty effective job of it so far. I would not allow this pompous, tubby little man to freak me out.

‘Now before we talk about the promotions, I have some excellent news—a marvellous opportunity for you.’

‘Oh yes,’ I said, with a jaded cynicism I hoped he hadn’t detected.

‘You’ve heard of JJ Resources?’

I had. It was a large private company in the construction business and an established Pearson Malone client.

‘Now Venner’s gone we need a new tax partner. If you can pass muster with Jim Jupp himself, you’re in.’

JJ would have been a plum client, but FTSE-listed Megabuilders Plc had recently bid to take them over. After the deal, Megabuilders’ in-house department would take care of their tax work. And in the meantime, I would be stuck overseeing the responses to the purchaser’s due diligence questions and reviewing dreary tax warranties and indemnities. It wasn’t even as though the Jupp family shareholders needed any sexy tax planning done—that had long since been organised.

‘The company’s being sold,’ I said. ‘So it won’t be a client for much longer, will it?’

‘Such defeatist talk,’ said Smithies. ‘It’s up to you to use this opportunity to develop a relationship with Megabuilders so they’ll use us going forward.’

Unlikely.

‘Can’t Lisa Carter run with it?’

Lisa, the lynchpin of the JJ client team, was a director in my group. She was also my protégée and the closest approximation to a friend I had in Pearson Malone, or indeed anywhere.

‘Not appropriate, in the circumstances.’

‘I see,’ I said, although I didn’t see at all.

‘Eric Bailey thought you’d be ideal,’ he added, by way of encouragement.

I drew no comfort from this. Bailey, UK CEO of our firm, operated on a feudal system, handing out favours to his henchmen in exchange for their undying loyalty. It was dangerous to be the recipient of his largesse because of what might be demanded in return—particularly in this case. Everyone knew that Bailey and Jim Jupp, JJ Resources’ CEO, were best buddies. And while this personal connection strictly precluded any involvement with the client account, Bailey had no time for such tedious technicalities. He would interfere when it suited him and there’d be hell to pay if something went wrong.

If that wasn’t bad enough, Greg, my ex-husband, led the Corporate Finance team advising JJ on the Megabuilders transaction. I was bound to have a degree of contact with him during the process. Was Smithies trying to manufacture complications in my life? And if he truly believed I was ‘on edge’, why burden me with more work?

I quelled the internal sniping. What had got into me? This was a simple request to take on a client.

‘I’m pleased to have the opportunity,’ I said with Oscar-winning sincerity.

Yet still the queasy intuition gnawed at my guts.

‘Fish alright?’ he asked, his chubby fingers working to prise his meat from the bones and sinew. My stomach heaved—lamb was the worst for me.

‘Lovely, thanks.’

‘Tricky staying slim once you reach a certain age, isn’t it? No surprise that so many women end up with eating disorders.’

‘Not me,’ I said, prickling instinctively. Could I have an eating disorder without realising it, which Smithies had identified? He had this knack of making me doubt myself.

‘

Well, he’s not suffering from an eating disorder, that’s for sure,’

piped up the little voice from last week’s meeting.

‘Look at the size of that belly.’