Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) (65 page)

Read Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) Online

Authors: JOSEPH CONRAD

“What! That doubled-up crone?”

“Ah!” said Almayer. “They age quickly here. And long foggy nights spent in the bush will soon break the strongest backs — as you will find out yourself soon.”

“Dis . . . disgusting,” growled the traveller.

He dozed off. Almayer stood by the balustrade looking out at the bluish sheen of the moonlit night. The forests, unchanged and sombre, seemed to hang over the water, listening to the unceasing whisper of the great river; and above their dark wall the hill on which Lingard had buried the body of his late prisoner rose in a black, rounded mass, upon the silver paleness of the sky. Almayer looked for a long time at the clean-cut outline of the summit, as if trying to make out through darkness and distance the shape of that expensive tombstone. When he turned round at last he saw his guest sleeping, his arms on the table, his head on his arms.

“Now, look here!” he shouted, slapping the table with the palm of his hand.

The naturalist woke up, and sat all in a heap, staring owlishly.

“Here!” went on Almayer, speaking very loud and thumping the table, “I want to know. You, who say you have read all the books, just tell me . . . why such infernal things are ever allowed. Here I am! Done harm to nobody, lived an honest life . . . and a scoundrel like that is born in Rotterdam or some such place at the other end of the world somewhere, travels out here, robs his employer, runs away from his wife, and ruins me and my Nina — he ruined me, I tell you — and gets himself shot at last by a poor miserable savage, that knows nothing at all about him really. Where’s the sense of all this? Where’s your Providence? Where’s the good for anybody in all this? The world’s a swindle! A swindle! Why should I suffer? What have I done to be treated so?”

He howled out his string of questions, and suddenly became silent. The man who ought to have been a professor made a tremendous effort to articulate distinctly —

“My dear fellow, don’t — don’t you see that the ba-bare fac — the fact of your existence is off — offensive. . . . I — I like you — like . . .”

He fell forward on the table, and ended his remarks by an unexpected and prolonged snore.

Almayer shrugged his shoulders and walked back to the balustrade.

He drank his own trade gin very seldom, but when he did, a ridiculously small quantity of the stuff could induce him to assume a rebellious attitude towards the scheme of the universe. And now, throwing his body over the rail, he shouted impudently into the night, turning his face towards that far-off and invisible slab of imported granite upon which Lingard had thought fit to record God’s mercy and Willems’ escape.

“Father was wrong — wrong!” he yelled. “I want you to smart for it. You must smart for it! Where are you, Willems? Hey? . . . Hey? . . . Where there is no mercy for you — I hope!”

“Hope,” repeated in a whispering echo the startled forests, the river and the hills; and Almayer, who stood waiting, with a smile of tipsy attention on his lips, heard no other answer.

THE NIGGER OF THE NARCISSUS

A TALE OF THE FORECASTLE

This early novella is well-known for its quality compared to other works, and many critics believe it marks the start of Conrad’s major period.

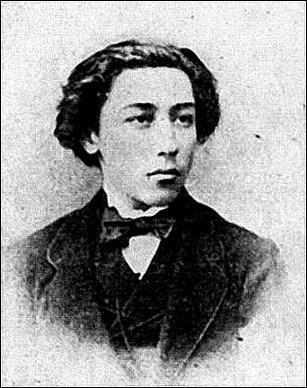

Conrad prior to his first voyage

CONTENTS

TO

EDWARD GARNETT

THIS TALE

ABOUT MY FRIENDS

OF THE SEA

TO MY READERS IN AMERICA

From that evening when James Wait joined the ship — late for the muster of the crew — to the moment when he left us in the open sea, shrouded in sailcloth, through the open port, I had much to do with him. He was in my watch. A negro in a British forecastle is a lonely being. He has no chums. Yet James Wait, afraid of death and making her his accomplice was an impostor of some character — mastering our compassion, scornful of our sentimentalism, triumphing over our suspicions.

But in the book he is nothing; he is merely the centre of the ship’s collective psychology and the pivot of the action. Yet he, who in the family circle and amongst my friends is familiarly referred to as the Nigger, remains very precious to me. For the book written round him is not the sort of thing that can be attempted more than once in a life-time. It is the book by which, not as a novelist perhaps, but as an artist striving for the utmost sincerity of expression, I am willing to stand or fall. Its pages are the tribute of my unalterable and profound affection for the ships, the seamen, the winds and the great sea — the moulders of my youth, the companions of the best years of my life.

After writing the last words of that book, in the revulsion of feeling before the accomplished task, I understood that I had done with the sea, and that henceforth I had to be a writer. And almost without laying down the pen I wrote a preface, trying to express the spirit in which I was entering on the task of my new life. That preface on advice (which I now think was wrong) was never published with the book. But the late W. E. Henley, who had the courage at that time (1897) to serialize my “Nigger” in the New Review judged it worthy to be printed as an afterword at the end of the last instalment of the tale.

I am glad that this book which means so much to me is coming out again, under its proper title of “The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’“ and under the auspices of my good, friends and publishers Messrs. Doubleday, Page & Co. into the light of publicity.

Half the span of a generation has passed since W. E. Henley, after reading two chapters, sent me a verbal message: “Tell Conrad that if the rest is up to the sample it shall certainly come out in the New Review.” The most gratifying recollection of my writer’s life!

And here is the Suppressed Preface.

1914.

JOSEPH CONRAD.

PREFACE

A work that aspires, however humbly, to the condition of art should carry its justification in every line. And art itself may be defined as a single-minded attempt to render the highest kind of justice to the visible universe, by bringing to light the truth, manifold and one, underlying its every aspect. It is an attempt to find in its forms, in its colours, in its light, in its shadows, in the aspects of matter and in the facts of life what of each is fundamental, what is enduring and essential — their one illuminating and convincing quality — the very truth of their existence. The artist, then, like the thinker or the scientist, seeks the truth and makes his appeal. Impressed by the aspect of the world the thinker plunges into ideas, the scientist into facts — whence, presently, emerging they make their appeal to those qualities of our being that fit us best for the hazardous enterprise of living. They speak authoritatively to our common-sense, to our intelligence, to our desire of peace or to our desire of unrest; not seldom to our prejudices, sometimes to our fears, often to our egoism — but always to our credulity. And their words are heard with reverence, for their concern is with weighty matters: with the cultivation of our minds and the proper care of our bodies, with the attainment of our ambitions, with the perfection of the means and the glorification of our precious aims.

It is otherwise with the artist.

Confronted by the same enigmatical spectacle the artist descends within himself, and in that lonely region of stress and strife, if he be deserving and fortunate, he finds the terms of his appeal. His appeal is made to our less obvious capacities: to that part of our nature which, because of the warlike conditions of existence, is necessarily kept out of sight within the more resisting and hard qualities — like the vulnerable body within a steel armour. His appeal is less loud, more profound, less distinct, more stirring — and sooner forgotten. Yet its effect endures forever. The changing wisdom of successive generations discards ideas, questions facts, demolishes theories. But the artist appeals to that part of our being which is not dependent on wisdom; to that in us which is a gift and not an acquisition — and, therefore, more permanently enduring. He speaks to our capacity for delight and wonder, to the sense of mystery surrounding our lives; to our sense of pity, and beauty, and pain; to the latent feeling of fellowship with all creation — and to the subtle but invincible conviction of solidarity that knits together the loneliness of innumerable hearts, to the solidarity in dreams, in joy, in sorrow, in aspirations, in illusions, in hope, in fear, which binds men to each other, which binds together all humanity — the dead to the living and the living to the unborn.

It is only some such train of thought, or rather of feeling, that can in a measure explain the aim of the attempt, made in the tale which follows, to present an unrestful episode in the obscure lives of a few individuals out of all the disregarded multitude of the bewildered, the simple and the voiceless. For, if any part of truth dwells in the belief confessed above, it becomes evident that there is not a place of splendour or a dark corner of the earth that does not deserve, if only a passing glance of wonder and pity. The motive then, may be held to justify the matter of the work; but this preface, which is simply an avowal of endeavour, cannot end here — for the avowal is not yet complete. Fiction — if it at all aspires to be art — appeals to temperament. And in truth it must be, like painting, like music, like all art, the appeal of one temperament to all the other innumerable temperaments whose subtle and resistless power endows passing events with their true meaning, and creates the moral, the emotional atmosphere of the place and time. Such an appeal to be effective must be an impression conveyed through the senses; and, in fact, it cannot be made in any other way, because temperament, whether individual or collective, is not amenable to persuasion. All art, therefore, appeals primarily to the senses, and the artistic aim when expressing itself in written words must also make its appeal through the senses, if its highest desire is to reach the secret spring of responsive emotions. It must strenuously aspire to the plasticity of sculpture, to the colour of painting, and to the magic suggestiveness of music — which is the art of arts. And it is only through complete, unswerving devotion to the perfect blending of form and substance; it is only through an unremitting never-discouraged care for the shape and ring of sentences that an approach can be made to plasticity, to colour, and that the light of magic suggestiveness may be brought to play for an evanescent instant over the commonplace surface of words: of the old, old words, worn thin, defaced by ages of careless usage.

The sincere endeavour to accomplish that creative task, to go as far on that road as his strength will carry him, to go undeterred by faltering, weariness or reproach, is the only valid justification for the worker in prose. And if his conscience is clear, his answer to those who in the fulness of a wisdom which looks for immediate profit, demand specifically to be edified, consoled, amused; who demand to be promptly improved, or encouraged, or frightened, or shocked, or charmed, must run thus: — My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel — it is, before all, to make you see. That — and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm — all you demand — and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask. To snatch in a moment of courage, from the remorseless rush of time, a passing phase of life, is only the beginning of the task. The task approached in tenderness and faith is to hold up unquestioningly, without choice and without fear, the rescued fragment before all eyes in the light of a sincere mood. It is to show its vibration, its colour, its form; and through its movement, its form, and its colour, reveal the substance of its truth — disclose its inspiring secret: the stress and passion within the core of each convincing moment. In a single-minded attempt of that kind, if one be deserving and fortunate, one may perchance attain to such clearness of sincerity that at last the presented vision of regret or pity, of terror or mirth, shall awaken in the hearts of the beholders that feeling of unavoidable solidarity; of the solidarity in mysterious origin, in toil, in joy, in hope, in uncertain fate, which binds men to each other and all mankind to the visible world. It is evident that he who, rightly or wrongly, holds by the convictions expressed above cannot be faithful to any one of the temporary formulas of his craft. The enduring part of them — the truth which each only imperfectly veils — should abide with him as the most precious of his possessions, but they all: Realism, Romanticism, Naturalism, even the unofficial sentimentalism (which like the poor, is exceedingly difficult to get rid of,) all these gods must, after a short period of fellowship, abandon him — even on the very threshold of the temple — to the stammerings of his conscience and to the outspoken consciousness of the difficulties of his work. In that uneasy solitude the supreme cry of Art for Art itself, loses the exciting ring of its apparent immorality. It sounds far off. It has ceased to be a cry, and is heard only as a whisper, often incomprehensible, but at times and faintly encouraging.