Complete Works of Emile Zola (1033 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

Advertising of the time for the publication of the novel in serial format

CONTENTS

CHAPTER XII

Poster of the film version of 1938

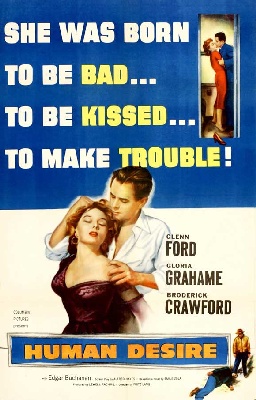

Poster for an American film adaptation, 1954

PREFACE

THIS striking work, now published for the first time in England, but a hundred thousand copies whereof have been sold in France, is one of the most powerful novels that M. Émile Zola has written. It will be doubly interesting to English readers, because for them it forms a missing link in the famous Rougon-Macquart series.

The student of Zola literature will remember in the

Assommoir

that “handsome Lantier whose heartlessness was to cost Gervaise so many tears.” Jacques Lantier, the chief character in this

Bite Humaine

, this

Human Animal

which I have ventured to call the

Monomaniac

, is one of their children. It is he who is the monomaniac. His monomania consists in an irresistible prurience for murder, and his victims must be women, just like that baneful criminal who was performing his hideous exploits in the streets of the city of London in utter defiance of the police, about the time M. Zola sat down to pen this remarkable novel, and from whom, maybe, he partly took the idea.

Every woman this Jacques Lantier falls in love with, nay, every girl from whom he culls a kiss, or whose bare shoulders or throat he happens to catch a glimpse of, he feels an indomitable craving to slaughter! And this abominable thirst is, it appears, nothing less than an irresistible desire to avenge certain wrongs of which he has lost the exact account, that have been handed down to him, through the males of his line, since that distant age when prehistoric man found shelter in the depths of caverns.

Around this peculiar being, who in other respects is like any ordinary mortal, M. Emile Zola has grouped some very carefully studied characters. All are drawn with a firm, masterly hand; all live and breathe. Madame Lebleu, caught with her ear to the keyhole, is worthy of Dickens. So is Aunt Phasie, who has engaged in a desperate underhand struggle with her wretch of a husband about a miserable hoard of £40 which he wants to lay hands on. The idea of the jeering smile on her lips, which seem to be repeating to him, “Search! search!” as she lies a corpse on her bed in the dim light of a tallow candle, is inimitable.

The unconscious Séverine is but one of thousands of pretty Frenchwomen tripping along the asphalt at this hour, utterly unable to distinguish between right and wrong, who are ready to do anything, to sell themselves body and soul for a little ease, a few smart frocks, and some dainty linen. The warrior girl Flore, who thrashes the males, is a grand conception.

But the gem of the whole bunch is that obstinate, narrow minded, self-sufficient examining-magistrate, M. Denizet; and in dealing with this character, the author lays bare all the abominable system of French criminal procedure. | Recently this was modified to the extent of allowing the accused party to have the assistance of counsel while undergoing the torture of repeated searching cross-examinations at the hands of his tormentor. But in the days of which M. Émile Zola is writing, the prisoner enjoyed no such protection. He stood alone in the room with the examining magistrate and his registrar, and while the former craftily laid traps for him to fall into, the latter carefully took down his replies to the incriminating questions addressed to him. It positively makes one shudder to think how many innocent men must have been sent to the guillotine, or to penal servitude for life, like poor Cabuche, during the length of years this atrocious practice remained in full vigour!

The English reader, accustomed to open, even-handed justice for one and all alike, and unfamiliar with the ways that prevail in France, will start with amazement and incredulity at the idea of shelving criminal cases to avoid scandal involving persons in high position. But such is by no means an uncommon proceeding on the other side of the straits. Georges Ohnet introduces a similar incident into his novel

Le Droit de L’Enfant —

M. Émile Zola has made most of his books a study of some particular sphere of life in France. In this instance he introduces his readers to the railway and railway servants. They are all there, from the station-master to the porter, and all are depicted with so skilful a hand that anyone who has travelled among our neighbours must recognise them.

By frequent runs on an express engine between Paris and Havre, and vice versa, the author has mastered all the complicated mechanism of the locomotive; and we see his trains vividly as in reality, starting from the termini, gliding along the lofty embankments, through the deep cuttings, plunging into and bursting from the tunnels amidst the deafening riot of their hundred wheels, while the dumpy habitation of the gatekeeper, Misard, totters on its frail foundations as they fly by in a hurricane blast.

The story teems with incident from start to finish. Each chapter is a drama in itself. To name but a few of the exciting events that are dealt with: there is a murder in a railway carriage; an appalling railway accident; a desperate fight between driver and fireman on the foot-plate of a locomotive, which ends in both going over the side to be cut to pieces, while the long train of cattle-trucks, under no control, crammed full of inebriated soldiers on their way to the war, who are yelling patriotic songs, dashes along, full steam, straight ahead, with a big fire just made up, onward; to stop, no one knows where.

This is certainly one of the best and most dramatic novels that M. Émile Zola has ever penned; and I feel lively pleasure at having the good fortune to be able, with the assistance of my enterprising publishers, to present it to the English reading public.

EDWARD VIZETELLY.

SURBITON,

August 20, 1901. —

CHAPTER I

ROUBAUD, on entering the room, placed the loaf, the pâté, and the bottle of white wine on the table. But Mother Victoire, before going down to her post in the morning, had crammed the stove with such a quantity of cinders that the heat was stifling, and the assistant station-master, having opened a window, leant out on the rail in front of it.

This occurred in the Impasse d’Amsterdam, in the last house on the right, a lofty dwelling, where the Western Railway Company lodged some of their staff. The window on the fifth floor, at the angle of the mansarded roof, looked on to the station, that broad trench cutting into the Quartier de l’Europe, to abruptly open up the view, and which the grey mid-February sky, of a grey that was damp and warm, penetrated by the sun, seemed to make still wider on that particular afternoon.

Opposite, in the sunny haze, the houses in the Rue de Rome became confused, fading lightly into distance. On the left gaped the gigantic porches of the iron marquees, with their smoky glass. That of the main lines on which the eye looked down, appeared immense. It was separated from those of Argenteuil, Versailles, and the Ceinture railway, which were smaller, by the buildings set apart for the post-office, and for heating water to fill the foot-warmers. To the right the trench was severed by the diamond pattern ironwork of the Pont de l’Europe, but it came into sight again, and could be followed as far as the Batignolles tunnel.

And below the window itself, occupying all the vast space, the three double lines that issued from the bridge deviated, spreading out like a fan, whose innumerable metal branches ran on to disappear beneath the span roofs of the marquees. In front of the arches stood the three boxes of the pointsmen, with their small, bare gardens. Amidst the confused background of carriages and engines encumbering the rails, a great red signal formed a spot in the pale daylight. —

Roubaud was interested for a few minutes, comparing what he saw with his own station at Havre. Each time he came like this, to pass a day at Paris, and found accommodation in the room of Mother Victoire, love of his trade got the better of him. The arrival of the train from Mantes had animated the platforms under the marquee of the main lines; and his eyes followed the shunting engine, a small tender engine with three low wheels coupled together, which began briskly bustling to and fro, branching off the train, dragging | away the carriages to drive them on to the shunting lines. Another engine, a powerful one this, an express engine, with two great devouring wheels, stood still alone, sending from its chimney a quantity of black smoke, which ascended straight, and very slowly, through the calm air.

But all the attention of Roubaud was centred on the 3.25 train for Caen, already full of passengers and awaiting its locomotive, which he could not see, for it had stopped on the other side of the Pont de l’Europe. He could only hear it asking for permission to advance, with slight, hurried whistles, like a person becoming impatient. An order resounded. The locomotive responded by one short whistle to indicate that it had understood. Then, before moving, came a brief silence. The exhaust pipes were opened, and the steam went hissing on a level with the ground in a deafening jet He then noticed this white cloud bursting from the bridge in volume, whirling about like snowy fleece flying through the ironwork. A whole corner of the expanse became whitened, while the smoke from the other engine expanded its black veil. From behind the bridge could be heard the prolonged, muffled sounds of the horn, mingled with the shouting of orders and the shocks of turning-tables. All at once the air was rent, and he distinguished in the background a train from Versailles, and a train from Auteuil, one up and one down, crossing each other.

As Roubaud was about to quit the window, a voice calling him by name made him lean out. Below, on the fourth floor balcony, he recognised a young man about thirty years of age, named Henri Dauvergne, a headguard, who resided there with his father, deputy station-master for the main lines, and his two sisters, Claire and Sophie, a couple of charming blondes, one eighteen and the other twenty, who looked after the housekeeping with the 6,000 frcs. of the two men, amidst a constant stream of gaiety. The elder one would be heard laughing, while the younger sang, and a cage full of exotic birds rivalled one another in roulades.

“By Jove, Monsieur Roubaud! so you are in Paris, then? Ah! yes, about your affair with the sub-prefect!

”

The assistant station-master, leaning on the rail again, explained that he had to leave Havre that morning by the 6.40 express. He had been summoned to Paris by the traffic manager, who had been giving him a serious lecture. He considered himself lucky in not having lost his post.

“And madam?” Henri inquired.

Madame had wished to come also, to make some purchases. Her husband was waiting for her there, in that room which Mother Victoire placed at their service whenever they came to Paris. It was there that they loved to lunch, tranquil and alone, while the worthy woman was detained downstairs at her post. On that particular day they had eaten a roll at Mantes, wishing to get their errands over first of all. But three o’clock had struck, and he was dying with hunger. Henri, to be amiable, put one more question:

“And are you going to pass the night in Paris?”

No, no! Both were returning to Havre in the evening by the 6.30 express. Ah! holidays, indeed! They brought you up to give you your dose, and off, back again at once!

The two looked at one another for a moment, tossing their heads, but they could no longer hear themselves speak; a devil-possessed piano had just broken into sonorous notes. The two sisters must have been thumping on it together, laughing louder than ever, and exciting the exotic birds. Then the young man gained by the merriment, said goodbye to withdraw into the apartment; and the assistant station-master, left alone, remained a moment with his eyes on the balcony whence ascended all this youthful gaiety. Then, looking up, he perceived the locomotive, whose driver had shut off the exhaust pipes and which the pointsman switched on to the train for Caen. The last flakes of white steam were lost amid the heavy whirling cloud of smoke soiling the sky. And Roubaud also returned into his room.