Complete History of Jack the Ripper (32 page)

Read Complete History of Jack the Ripper Online

Authors: Philip Sudgen

Reminders of the tragedies there surely were. The proprietor of the waxworks, exhibiting outside his premises his ‘horrible pictorial representations’ of the murders, was still turning them to profitable account. And a newsvendor, standing with a bundle of papers under one arm, was exhorting passers-by to read the latest on the atrocities between alternate puffs at the half cigar he shared with a neighbouring shoeblack. But of the menace of the unknown killer there was now little trace.

Even away from the reassuring razzle-dazzle of Whitechapel Road, near the scenes of the very crimes themselves, the journalist found people heedless of the danger. On the spot where Polly Nichols had been done to death in Buck’s Row he found a man grinding out ‘Men of Harlech’ on a piano organ. And in Hanbury Street he stopped an elderly pedestrian. ‘There seems to be little apprehension of further mischief by this assassin at large?’ he asked him. ‘No, very little,’ the old man replied. ‘People, most of ’em, think he’s gone to Gateshead.’

Just a few nights later, on 30 September, the murderer struck again. And this time he claimed two victims in less than an hour.

Double Event

O

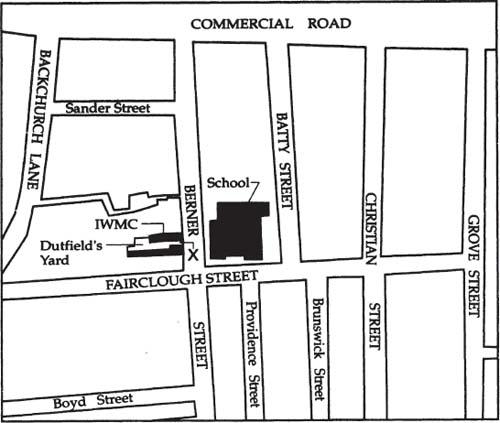

N THE SOUTH SIDE

of Commercial Road was Berner Street. A thoroughfare of small two-storey slums in the parish of St George-in-the-East, its inhabitants – tailors, shoemakers and cigarette makers – were mostly Poles and Germans. On the west side of Berner Street, directly opposite a new London School Board building, was Dutfield’s Yard. The name was no longer appropriate since Arthur Dutfield’s business had moved to Pinchin Street but the two great wooden gates that guarded the entrance to the yard still proclaimed the connection in letters of white paint: ‘W. Hindley, sack manufacturer, and A. Dutfield, van and cart builder.’

Inside the gates Dutfield’s Yard was a narrow court flanked on the right by the International Working Men’s Educational Club at 40 Berner Street and on the left by No. 42 and, behind that, a row of cottages. At the top of the yard were a store or workshop belonging to Hindley’s sack manufactory and a disused stable.

The International Working Men’s Educational Club was a Socialist club. Membership was open to working men of any nationality but it was mainly patronized by Russian and Polish Jews. Access to the premises could be gained by the front door in Berner Street or by a side or kitchen door in Dutfield’s Yard. The most northerly of the big yard gates had a wicket for use when the main gates were closed. But they were frequently left open, even at night. ‘In fact,’ said a club member, ‘it is very seldom that they are closed. It is customary for members of the club to go in by the side door to prevent knocking at the front.’

1

On Saturday nights there were free discussions at the club and although the night of Saturday, 29 September, was wet and dismal some ninety to one hundred people crowded into the first-floor meeting room to debate ‘why Jews should be Socialists.’ Morris Eagle, a Russian Jew, took the chair. When the discussion ended, between 11.30 and 12.00, the bulk of the clientele went home but perhaps a few dozen members stayed. Most of these remained chatting or singing in the meeting room upstairs.

Outside, in the yard, it must have been dark. Mrs Diemschutz, the stewardess of the club, later told reporters that at about one the side door ‘had been, and still was, half open, and from it the light from the gas jets in the kitchen was streaming out into the yard.’ Light also came from the cottage windows, from the first-floor windows of the club and from a printing office at the back of the club where Philip Kranz, the editor of a Yiddish radical weekly

Der Arbeter Fraint

(

The Worker’s Friend

), was still reading in his room. But no lamp shone in the yard itself. And the illumination from the upper storey of the club fell not so much upon the court below as upon the cottages opposite. Furthermore, whatever benefits the club’s side door, the cottages and the printing office conferred farther up the yard, they did little to penetrate the gloom immediately within the gates. Here, for a distance of some eighteen feet from the street, anyone entering the yard had to pass between the dead walls of Nos. 40 and 42. Here, after sunset, the darkness was almost absolute.

Although dark Dutfield’s Yard was by no means unfrequented. We know the names of three members of the club who visited it between midnight and one that night.

2

Others probably came and went unrecorded.

About ten minutes past midnight William West popped out of the club by the side door to take some literature to the printing office where he worked farther up the yard. Returning, he glanced towards the gates and noticed that they were open. But he saw nothing suspicious there. Then he re-entered the club, again using the side door, called his brother and set off home. They left by the Berner Street door at about 12.15 a.m.

Joseph Lave, a printer and photographer visiting London from the United States, had temporary lodgings at the club. ‘I was in the club yard this morning about twenty minutes to one,’ he would tell a reporter later in the day. ‘I came out first at half-past twelve to get a breath of fresh air. I passed out into the street, but did not see

anything unusual. The district appeared to me to be quiet. I remained out until twenty minutes to one, and during that time no one came into the yard. I should have seen anybody moving about there.’

After the Saturday night debate Morris Eagle, the chairman, escorted his lady friend home. At about 12.40 he returned. When he tried the street door he found it closed so he walked round the side into Dutfield’s Yard. The gates were thrown wide open. As soon as he passed through the gateway he could hear, from the open first-floor windows of the club, the strains of a friend singing in Russian. Entering by the side door, he went upstairs and joined in. Just twenty minutes later the huddled body of a woman was discovered lying by the wall of the club between the gates and the side door. Yet Eagle, walking that same ground, had seen nothing. Nor did he remember noticing anyone in the yard. His testimony is good evidence that at 12.40 the crime had not yet been committed. The site of the murder was in the passage between Nos. 40 and 42, where it was too dark to enable Eagle to swear positively at the inquest that the body had

not

been there. But the corpse would be found lying obliquely across the pathway, both face and feet very close to the right-hand wall, and had it been there at 12.40 Eagle, passing up the yard, would very likely have brushed against it, if not have actually stumbled over it. ‘I naturally walked on the right side [of the path],’ he explained, ‘that being the side on which the club door was.’

3

At 1.00 a.m. on Sunday, 30 September, a man driving a two-wheeled barrow harnessed to a pony approached Dutfield’s Yard.

4

The driver was a Russian Jew named Louis Diemschutz. He was the steward of the International Working Men’s Educational Club and he lived on the premises with his wife, who assisted him in the management. In addition to being the club steward Diemschutz was a hawker of cheap jewellery and every Saturday he took wares to sell in the market at Westow Hill, Crystal Palace. Now, after the day’s trading, he had come to deposit his unsold stock at the club before stabling his pony in George Yard, Cable Street.

The steward noticed nothing untoward as he turned into the gateway. He heard no cry, he saw no one about and certainly there was nothing unusual in the fact that both gates were wide open. Yet, as he drove into the yard, his pony shied to the left. Peering down to the right, Diemschutz thought that he could discern a dark object on the ground by the club wall but it was too dark for him to see what it was. He prodded it and tried to lift it with the handle of his whip. Then he jumped down from his barrow and struck a match. It was windy but before his feeble flame was extinguished the steward could make out the shape of a prone figure. And the dim outline of a dress told him that the figure was that of a woman.

Berner Street and its vicinity.

×

marks the place where Elizabeth Stride’s body was discovered, at 1 a.m. on Sunday, 30 September 1888

Diemschutz’s first concern was for his wife. Perhaps he thought it was she lying there. Or perhaps, as he would tell the press, ‘all I did was to run indoors and ask where my missis was because she is of weak constitution, and I did not want to frighten her.’ Whatever the reason, leaving his pony at the side door, he dashed into the club and enquired for his wife. He found her, safe in the company of some of the members in the ground-floor dining room, and then stammered: ‘There’s a woman lying in the yard but I cannot say whether she’s drunk or dead.’

Having procured a candle and reinforcements in the form of Isaac

Kozebrodski, a young tailor machinist, Diemschutz ventured back into the yard. Even before they reached the body they could see blood. Mrs Diemschutz followed them but only as far as the kitchen door. ‘Just by the door,’ she later explained to journalists, ‘I saw a pool of blood, and when my husband struck a light I noticed a dark heap lying under the wall. I at once recognized it as the body of a woman, while, to add to my horror, I saw a stream of blood trickling down [i.e. up] the yard and terminating in the pool I had first noticed. She was lying on her back with her head against the wall, and the face looked ghastly. I screamed out in fright, and the members of the club hearing my cries rushed downstairs in a body out into the yard.’

Diemschutz and Kozebrodski made no attempt to disturb the body. Instead they immediately set off in search of a policeman. Turning right at the gates and then left into Fairclough Street, they raced with pounding hearts, shouting ‘Police!’ at the tops of their voices, as far as Grove Street. But no constable did they descry and there they turned back. On the way to Grove Street they had passed a horse-keeper by the name of Edward Spooner.

Spooner was standing with a woman outside the Beehive Tavern, at the corner of Christian and Fairclough Streets, when he saw the two Jews running and ‘hallooing out “Murder” and “Police”’. They passed him but stopped at Grove Street and came back. Intrigued to discover what all the fuss was about, Spooner accosted them. And when they told him that another woman had been murdered he returned with them to Dutfield’s Yard. Upon reaching the yard they found a small crowd already clustered around the body. Someone struck a match and Spooner bent down and lifted up the dead woman’s chin. It was just warm and he noticed blood still flowing from her throat and running up the yard towards the side door of the club. When the horse-keeper lifted the woman’s chin Louis Diemschutz, looking on, saw for the first time the terrible wound in her throat. ‘I could see that her throat was fearfully cut,’ he told the press some hours later. ‘There was a great gash in it over two inches wide.’

At the time of Diemschutz’s discovery of the body most of the members remaining on the club premises were still upstairs singing. But when someone came up to tell them that there was a dead woman in the yard Morris Eagle for one tumbled pell-mell down the stairs and out at the side door. ‘I went down in a second and struck a match,’ he would tell the inquest. Notwithstanding his alacrity, Eagle took very

little cognizance of the appearance of the body. As he explained it later to a representative of the press, ‘I did not notice the appearance of the woman because the sight of the blood upset me and I could not look at it.’ He it was, however, who informed the police. For whereas Diemschutz had turned southwards from the gateway towards Fairclough Street Eagle sped in the opposite direction. And in Commercial Road he encountered PC Henry Lamb 252H and a brother constable.

Lamb’s beat in Commercial Road took him past the end of Berner Street. He had last passed it only six or seven minutes earlier. And it was between Christian and Batty Streets on his way back that he first saw two men shouting and running towards him from the direction of Berner Street. They were Morris Eagle and a companion. He advanced to meet them. ‘Come on,’ they cried, ‘there has been another murder.’ Followed by another constable fresh from a fixed point duty in Commercial Road, Lamb ran to the scene of the crime.

There was a crowd there and when he turned his lantern on the body the bystanders eagerly pressed forward to see. ‘I begged them to keep back,’ Lamb told the inquest, ‘otherwise they might have their clothes soiled with blood and thus get into trouble.’

Kneeling down, he placed his hand against the woman’s face. It was slightly warm. Then he felt her wrist but could detect no movement of the pulse. Lamb was uncertain as to whether blood was still flowing from the wound in the throat but he did note that the blood which had run towards the club door was still in a liquid state. That on the ground near to the woman’s neck was slightly congealed. There were no signs of a struggle and the woman’s clothes did not appear to have been disturbed. Only the soles of her boots were visible from beneath her voluminous skirts. ‘She looked,’ said Lamb, ‘as if she had been laid quietly down.’