Complete History of Jack the Ripper (18 page)

Read Complete History of Jack the Ripper Online

Authors: Philip Sudgen

In the week previous to her murder Annie was not at the lodging house. The only glimpses we get of her come from her friend Amelia Palmer. On Monday, 3 September, Amelia met her in Dorset Street and noticed a bruise on her right temple. ‘How did you get that?’ she asked. By way of reply Annie opened her dress. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘look at my chest.’ And she showed Amelia a second bruise. Their talk passed from Annie’s fight to other things. ‘If my sister will send me the boots,’ declared Annie, ‘I shall go hopping [i.e. hop-picking].’

The next day Amelia saw Annie again near Spitalfields Church. Annie said that she felt no better and that she should go into the casual ward for a day or two. Amelia remarked that she looked very pale and asked if she had had anything to eat. ‘No,’ replied Annie, ‘I haven’t had a cup of tea today.’ Amelia gave her 2d. to get some but told her not to spend it on rum.

Amelia last saw Annie alive on Friday, 7 September. At about 5.00 p.m. they met in Dorset Street. ‘Aren’t you going to Stratford today?’ queried Amelia. ‘I feel too ill to do anything,’ said Annie. Some ten minutes later Amelia found her standing in the same spot, it’s no use giving way,’ Annie said, ‘I must pull myself together and get some money or I shall have no lodgings.’

Earlier that same day, the last of Annie’s life, she had turned up again at 35 Dorset Street. Between two and three in the afternoon she arrived at the lodging house and asked to be allowed to sit downstairs in the kitchen. Donovan asked her where she had been all week and she told him that she had been ‘in the infirmary’.

2

Annie seems to have been coming and going for the rest of the day. Soon after midnight she came in saying that she had been to Vauxhall to see her sister. A fellow lodger told a newspaper that she went to ‘get some money’ and that her relatives gave her 5d.

3

If so it was quickly expended on drink. John Evans informed the inquest that upon her return she sent one of the lodgers for a pint of beer and then popped out again herself.

At about 1.30 or 1.45 a.m. on Saturday, 8 September, Annie was sitting in the kitchen, enjoying the warmth, eating potatoes and gossiping with the other lodgers. Donovan sent Evans to ask for her lodging money. Annie came up to the office. ‘I haven’t sufficient money for my bed,’ she told the deputy, ‘but don’t let it. I shall not be long before I am in.’ Donovan was scarcely sympathetic. ‘You can find money for your beer,’ he admonished her, ‘and you can’t find money for your bed.’ But Annie was not dismayed. She would get the money. Leaving the office, she stood two or three minutes in the doorway. ‘Never mind, Tim,’ she repeated, ‘I shall soon be back. Don’t let the bed.’ Evans, who had followed Annie upstairs now saw her off the premises. As she left the house, he told the inquest two days later, he watched her go. Not drunk but slightly the worse for drink, she walked through Little Paternoster Row into Brushfield Street and then turned towards Spitalfields Church. It was about 1.50 a.m.

4

A little after six Annie’s dead and mutilated body was discovered in the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields, just three or four hundred yards away from her lodging.

No. 29 was a three-storeyed house on the north side of the street. Built for Spitalfields weavers, it had been converted into dwellings for the labouring poor after steam had banished the hand loom. By 1888 the toll of time was beginning to show on its facade. It was a dingy property flanked by equally dingy neighbours, on one side a dwelling house and on the other, its yellow paint peeling from its walls like skin disease, a mangling house. Yet a discerning observer might have detected remnants of pride about No. 29. A signboard above the street door proudly proclaimed in straggling white letters: ‘Mrs A. Richardson, rough packing-case maker.’ And the windows of the first floor front room, in which Mrs Richardson slept, were adorned with red curtains and filled with flowers.

At the time of the murder No. 29 was a veritable nest of living beings. Mrs Amelia Richardson, a widow, rented part of it and sublet some of the rooms. She slept with her fourteen-year-old grandson in the first floor front room and used two other rooms. The cellar in the backyard housed her packing case workshops. In the ground

floor back room she did her cooking and held weekly prayer meetings. The front room on the ground floor was a cats’ meat shop. The proprietress, Mrs Harriet Hardiman, slept in the shop with her sixteen-year-old son. Mr Waker, a maker of tennis boots, and his adult but mentally retarded son occupied the first floor back. The second floor front was tenanted by Mr Thompson, a carman, his wife and their adopted daughter. Two unmarried sisters who worked in a cigar factory lived in the back room on the same floor. The front room in the attic housed John Davis, another carman, together with his wife and three sons. While Mrs Sarah Cox, a ‘little old lady’ who Mrs Richardson maintained out of charity, occupied a back room in the attic. No less than seventeen persons thus resided permanently at No. 29. Others had legitimate business there. John Richardson, Amelia’s son, and Francis Tyler, her hired hand, for example, both assisted her in her packing case business and used the cellar workshops.

5

There must have been much coming and going and on market mornings at least the day began early. On Saturday, 8 September, the morning of the murder, Thompson went out for work at about 3.50. Mrs Richardson, dozing fitfully on the first floor, heard him leave and called out ‘good morning’ as he passed her room. Between 4.45 and 4.50 John Richardson visited the house on his way to work in Spitalfields Market. He called in to check on the security of the cellar. John Davis got up at 5.45 and went down to the backyard about a quarter of an hour later. And Francis Tyler, the hired help, should have started work at six. He was, however, frequently late. On the fatal Saturday he had to be sent for and didn’t turn up until eight.

Intruders might also be found on the premises. By the shop door in Hanbury Street was a side door which gave access to the rest of the building from the street. It opened into a twenty or twenty-five foot passage. A staircase led to the upper floors and at the end of the passage was a back door giving access to the backyard. Most of the houses in the area, like No. 29, were let out in rooms and many of the tenants were market folk, leaving home early in the morning, some as early as one. It thus became the general practice to leave street and back doors unlocked for their convenience and the inevitable result was the regular appearance in these houses of trespassers. One morning Thompson challenged a man on the stairs of No. 29. ‘I’m waiting for the market,’ said the man. ‘You’ve no right here, guv’nor,’ replied Thompson. Prostitutes and their clients also used the premises. John Richardson told the inquest that he had found prostitutes and other strangers there at all hours of the night and had often turned them out.

In taking his victim into the backyard of No. 29, therefore, the murderer, perhaps unknowingly, exposed himself to some risk. Yet the regular traffic in and out of the house also facilitated his purpose.

For the permanent residents would scarcely have suspected anything amiss in the stealthy footsteps of the killer and his victim.

The backyard in which the body was found is of special interest to us. Although the house has long been demolished its appearance has been preserved in contemporary descriptions and drawings, in a few subsequent photographs, and in a rare piece of footage in that delightful if neglected James Mason film

The London Nobody Knows.

Three stone steps led from the back door down into the yard. It was perhaps five yards by four, in some places bare earth, in others roughly paved with flat or round stones. Close wooden palings, about five and a half feet high, fenced it off on both sides from the adjoining yards. Standing on the steps, an observer would have seen, three or three and a half feet to his left, the palings that separated the yard from that of No. 27. In the far left-hand corner, opposite the back door, was Mrs Richardson’s woodshed. In the far right-hand corner was a privy. The entrance to the cellar, which contained Mrs Richardson’s workshops, lay immediately to the right of the back door.

It was John Davis the carman who found Annie’s body. He is described in the press as a small, elderly man with a decided stoop. He rented a room in the attic of No. 29, where he lived with his wife and three sons. For much of the night of 7–8 September Davis could not sleep. From three to five he lay awake and then he dozed until the clock at Spitalfields Church struck 5.45. That, and the light stealing through his large weaver’s window, told him that it was time to bestir himself for another day’s toil in Leadenhall Market. Davis and his wife got up. She made him a cup of tea and then he trudged downstairs to the backyard. Downstairs he noticed that the street door was wide open and thrown back against the wall. That was not unusual. The back door was closed. He opened it and stood at the top of the steps leading into the yard. The sight that met his casual glance shook him to his boots.

The body of a woman, sprawled upon its back, lay in the yard to his left, between the steps and the wooden fence adjoining No. 27. Her head was towards the house, her feet towards the woodshed, and Davis noticed that her skirts had been raised to her groin. He did not wait to investigate further. Hurrying through the passage, he stumbled out of the front door and into the street. There two packing case makers, James Green and James Kent, who worked for Joseph and Thomas Bayley of 23A Hanbury Street, were standing outside their workshop waiting for fellow workmen to arrive. And there, passing through Hanbury Street on his way to work, was a boxmaker named Henry John Holland. Their attention was arrested by a wild-eyed old man who suddenly burst from the doorway of No. 29. ‘Men,’ he cried, ‘come here!’

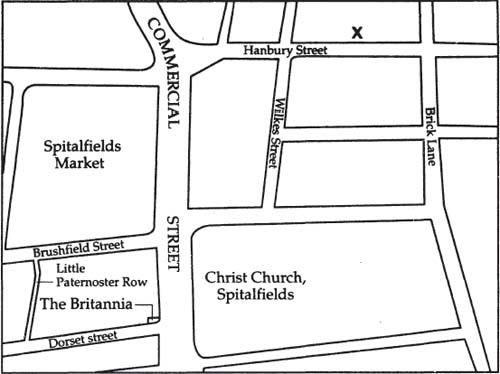

Hanbury Street and vicinity.

×

marks No. 29, where the body of Annie Chapman was discovered, at about 6.00 a.m. on 8 September 1888

The workmen followed Davis back down the passage and gazed at the body from the top of the yard steps. Davis, Kent and Green stood nervously at the back door. Holland, by his own account, ventured down into the yard itself but did not touch the body. Then they dispersed to find a policeman. Kent seems to have been thoroughly shaken by the experience. When he couldn’t see a constable from the front of the house he poured himself a brandy and then pottered about his workshop in search of a piece of canvas to throw over the body. By the time that he returned to No. 29 Inspector Chandler had

taken possession of the yard and a crowd had gathered in the passage and about the back door. ‘Everyone that looked at the body,’ recalled Kent, ‘seemed frightened as if they would run away.’

By the time that Chandler arrived the whole house had been alarmed. Mrs Hardiman, sleeping in the ground floor shop, had been disturbed by the heavy traffic through the passage. She imagined that there must be a fire and sent her son to investigate. ‘Don’t upset yourself, mother,’ he told her when he returned, ‘it’s a woman been killed in the yard!’ Mrs Hardiman stayed in her room but Amelia Richardson, apprised of the news by her grandson, ventured down from the first floor. She found the passage clogged with spectators but none of them seemed inclined to view the body at close quarters for there was no one in the yard except the dead woman. Soon afterwards the inspector arrived and, as far as Amelia knew, he was the first to enter the yard.

6

At 6.10 Inspector Joseph Chandler, H. Division, was on duty in Commercial Street near the corner of Hanbury Street when he saw several men running towards him. ‘Another woman has been murdered,’ one of them gasped. There was no one in the backyard of No. 29 when Chandler arrived and, with the possible exception of Holland, he was the first to inspect the body closely. The woman lay at the bottom and to the left of the steps leading into the yard, parallel with the fencing dividing the yards of Nos. 29 and 27. Her head was nearly two feet from the back wall of the house and six or nine inches from the steps. She was lying on her back, her left arm resting on her left breast, her right arm lying down her right side, her legs drawn up and her clothes thrown up above her knees. The handiwork of the murderer had been literally ghoulish. In terse language Chandler recorded the grisly sight for his superiors later in the day:

I at once proceeded to No. 29 Hanbury Street, and in the back yard found a woman lying on her back, dead, left arm resting on left breast, legs drawn up, abducted, small intestines and flap of the abdomen lying on right side, above right shoulder, attached by a cord with the rest of the intestines inside the body; two flaps of skin from the lower part of the abdomen lying in a large quantity of blood above the left shoulder; throat cut deeply from left and back in a jagged manner right around throat.

7