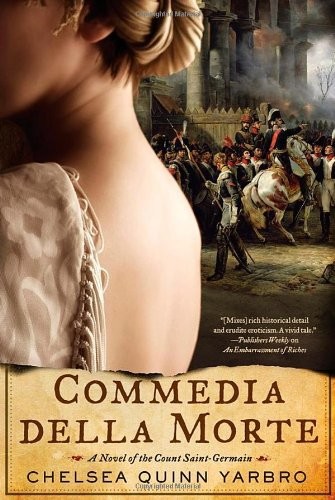

Commedia della Morte

Read Commedia della Morte Online

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

This one is for

Marsha Quick

with thanks times two.

Contents

Part I. Photine Therese d’Auville

Text of a Notice of Detention for Madelaine de Montalia

Part II. Ragoczy Ferenz, Conte da San-Germain

Text of a Letter from Oddysio Lisso to Ragoczy Ferenz

Part III. Madelaine Roxanne Bertrande de Montalia

Text of a Letter to the Department of Public Safety in Lyon

By Chelsea Quinn Yarbro from Tom Doherty Associates

Author’s Note

The latter part of the French Revolution is known as the Terror—roughly 1793–1795—and with good reason: carnage was at an all-time high during those hectic years, impacting almost everyone in the country. Denouncements with the flimsiest backup were often sufficient to doom an individual or a family to hasty death; shortly after the end of this story, a law was enacted which declared that accusation was the same as conviction, and the havoc was racheted up across the country. Many of the records of that period still remain, and they reveal a state of civic policy that was as capricious as it was lethal. Although the upper classes were the most consistently accused, they were also those who gained the most interest outside of France, so that much of what we know from that time is colored by showing more attention to those of high social standing than those of more modest rank, many of whom suffered as much as their social superiors did. Nonetheless it is certainly true that even before the infamous law was enacted, those with high social rank were often targeted for no greater crime than being well-born. Intellectuals were another group who frequently found themselves before the Revolutionary Courts for what they said or thought; merchants could be accused of gouging in their pricing, and end up in prison for their failure to support the work of the Revolution. But the Terror did not pop out of nowhere; it was the product of increasing social hysteria as well as vicious political infighting.

Not all the damage was done by revolutionaries themselves: many gangs and factions took advantage of the social upheaval to gouge out what advantage they could from it, and through the opportunities presented by the legal chaos, to gain wealth and influence for themselves. Then the efforts to hold on to that power became paramount, leading to political skullduggery and corruption of staggering proportions that spread well beyond Paris—which, as the capital of the country and center of Old Regime activities, garnered the most international attention—to the country in general. This was especially true in such cities as Marseilles, Lyon, Toulon, Bordeaux, Arras, and Nantes, where various Revolutionary Tribunals and Revolutionary Assemblies vied with one another, the National Assembly in Paris, and other groups in an attempt to wield as much power as possible, and to be rid of any and all rivals. The desire for revenge against the aristocrats was of long standing, and readily inflamed through rhetoric and bribes, as well as the promise of advancement. Political deals as much as patriotism marked the Terror, and contributed to the rampant depredations of the various mobs. As the number of available aristocrats lessened, these cities, like Paris, targeted intellectuals, clergy, foreigners, and rich men with revolutionary zeal, because they were most often the objects of resentment by the lower classes who were the most tenacious of the revolutionaries in these regionally important cities. Although many of these excesses are not as well documented as the events that took place in Paris, there are remaining records of the extremes embraced by many cities and towns at the height of the lunacy, as well as a vast number of scholarly studies on the reasons for and the results of those bloody years.

To handle all the various new regulations and laws, a massive new bureaucracy began to form, none more significant than the various Departments for Public Safety that sprang up in many cities, replacing what were viewed as hopelessly corrupt police forces. In time, these Departments became so powerful that by the time the Paris Committee for Public Safety was formed the power it had amassed was such that detention by its officers was sufficient to send those arrested to the guillotine without the nuisance of a trial, or the presentation of any evidence to support the arrest.

Calendar reform was under discussion but had not yet taken place, so dates at this time were generally consistent with the standard European calendar, although a few cities had developed reformed calendars of their own, and strove to put them into common use, but without any widespread success. For the sake of clarity, I’ve used the standard calendar even in cities where new municipal calendars were endorsed by Assemblies and Tribunals.

Dangerous as France was to many of its people, there were a few who managed to thrive in the turmoil without being part of the political systems: radical artists of all sorts were often welcomed by the Revolutionary Assemblies, not only to promote enthusiasm for the Revolution as a glorious event, but to provide some appearance of culture in the midst of pandemonium. Poets, novelists, painters, lyricists, singers, actors, and to a lesser extent journalists often enjoyed a hectic celebrity for as long as the public and the Revolutionary Assemblies and Tribunals endorsed the various principles the artists expressed, and so long as they were approved, they were the darlings of the public, lionized and revered by the men newly in power. Fame could then be a double-edged sword for the artist who fell from favor, for their very notoriety made escape and evasion unusually difficult. Those who managed to survive the Terror often became the leaders of the artistic movements of the early nineteenth century.

Travel at the time was precarious, and not simply for the usual reasons of poor roads and highway robbers—French border guards often imposed heavy customs payments on those entering France, and were known to seize the goods and livestock of those attempting to leave. Merchants from Italy, Spain, Holland, and Germany were regularly subjected to the threat of imprisonment if they refused to pay the outrageous sums demanded by the border guards. Peasants displaced from their lands often found themselves forced to give up their few possessions for the chance to leave the country alive. This kind of extortion was most prevalent in areas where the border guards were paid low wages or not paid at all, a circumstance tolerated by the Revolutionary Assemblies throughout the country as a means of demonstrating the advantage of cutting taxes; during the two years of the Terror these abuses increased until some of the guards themselves were condemned for betraying the Revolution and met with the same fate as the hapless aristocrats, clergy, and intellectuals did.

Neither Italy nor Germany at that time was united, which made response to the French Revolution a complicated matter, for each of the various duchies, kingdoms, bishoprics, states, palatinates, and other territories had their own dealings with France, or with regions of France, some of which were semi-autonomous. Most of the nobility of Europe were worried about the French Revolution, which they were justifiably afraid might spread beyond France. For that reason not all of the hodgepodge of countries were willing to receive refugees from the Terror, and most were wary about endorsing the Revolutionary Assemblies as legitimate governments, which lessened the number of escapees who sought out Italian and German havens. Great Britain took in a sizeable number of French refugees, as it had taken in French Protestants after the Saint-Bartholomew’s Day Massacre; so did Holland and Sweden, and a fair number of French fled to North and South America, with the greatest number in North America going to Quebec rather than to French centers in the United States; New Orleans, which had been used as a destination for deported French criminals, was not viewed as a desirable destination by many of those leaving France. Various political and intellectual groups in Britain and Scandinavia supported the French Revolution, among them the Lunar Society in Birmingham, England, who occasionally sent observers to cover the events, whose reports show growing concerns for the increasing excesses they observed. South American countries were divided on policies regarding Revolutionary refugees, although some found safety on Caribbean islands. Being adamantly Catholic, Spain became a refuge for many of the priests, monks, and nuns who were not willing to be martyrs to the New Order in France.

Well into the nineteenth century, French had a great many regional dialects and naming traditions, both for people and places, as well as dialects related to class. Some of the usages in this novel reflect those regionalisms, and are of the places and periods of the story and its characters; at the time of this book, French had been regularized for the educated, but a great percentage of the country kept to old forms of speech and nomenclature, which are reflected in these pages. One linguistic development of the Revolution was the incentive for towns with names associated with religion to change them to something more in tune with the times. Many of the new names were changed back after the rise of Napoleon and the subsequent return of the monarchy, but a few caught on and remain fixed to this day.

Since many, but not all, of the most active revolutionaries came from the working class, once most of the nobility and intelligentsia were dead or gone from the country, there were increasing flare-ups with the bourgeois; at the height of the Terror there was a sharp upturn in accusations against shopkeepers, artisans, manufacturers, and lawyers, a sign of the depths of what would later be called class warfare. Even servants could be condemned for no greater crime than earning a living. Few of the accused middle class had the means to flee, or the inclination to abandon their homes and businesses. The small number who could afford to leave almost everything behind and start over often chose not to, unwilling to admit defeat or to give the appearance of consenting to the claims of their accusers. Any supporters of these bourgeois rarely came forward on their behalf, wanting to avoid the scrutiny of the Revolutionary Tribunals, or the city mobs.

Fashions reflected the social change, shifting with unusual abruptness from Old Regime to Revolutionary modes. The mid-eighteenth century had been a period of opulence in dress, with upper-class men and women in costly fabrics and elaborate garments, wigs, and accessories that were copied on a less grand scale by as many of the middle class as could afford such display. By the time of the Revolution, fashions had become far less flamboyant; the “natural” look was in, often with a nod to the styles of ancient Greece in women’s clothes, when corsets were minimized and the waists of dresses moved up to just under the breasts, although that new line had not caught on in most circles at the time of this story. Wigs were rarely worn except on certain formal occasions, and knee-britches gave way to trousers. Simplicity in style was suddenly acceptable, and elaborate accessories and jewelry were replaced by far less conspicuous ornaments to dress, and restraint in jewelry. Cotton lawn and fine muslin replaced satin and silk; panniers and petticoats disappeared from formal women’s wear, at least for a quarter century. Another shift in fashion came in the form of household decor: from 1750 onward, improvements in the technology made the making of mirrors considerably less costly than it had been, and brought mirrors out of the realm of luxury items available to the wealthy few, into affordability for middle-class and bourgeois households. Having mirrors in businesses and houses became a sign of having arrived, and they were to be found almost everywhere.