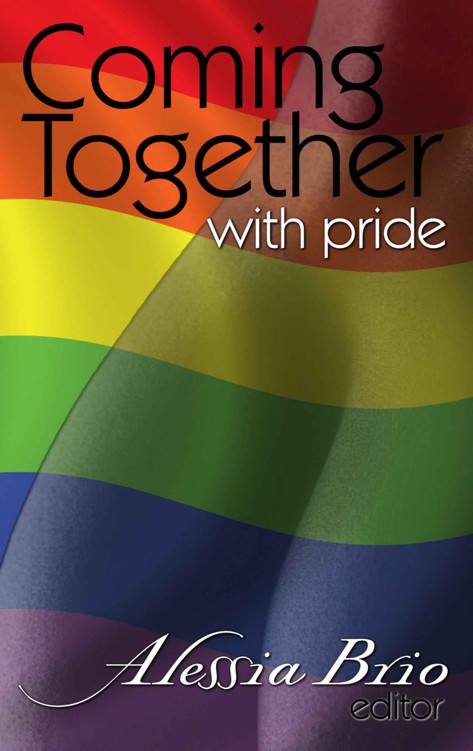

Coming Together: With Pride

Read Coming Together: With Pride Online

Authors: Alessia Brio

Coming Together

With Pride

Alessia Brio

editor

Coming Together: With Pride

© 2010 by

Alessia Brio

,

editor

This is a work of fiction. Names, places, characters and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to any actual persons, living or dead, organizations, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover art © 2010 by

Alessia Brio

All digital rights reserved under the International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Coming Together is intended for adult readers only.

Please keep this ebook away from children.

Coming Together: With Pride

is dedicated to the memory of

Lawrence Forbes King

an eighth grader,

who was killed by a classmate

because he was gay

Table of Contents

Almost thirty years ago, rumors started circulating about something worse than herpes. Yeah, herpes never went away—and we all thought that was about as horrible as it could get. Then, AIDS came along. We didn't call it that yet, though. We didn't know what to call it, but we knew it was deadly.

Only gay people got it, though. I didn't need to worry. It wouldn't affect me. Right?

Then one of my best friends came out, and he started dating a guy who grew up on my street. High school is a cruel environment under any circumstances, and I attended an all boy Catholic high school. The kind of environment where a rumor about somebody getting a hard-on in the locker room shower was all over the school in ten minutes. No place is as homophobic as an all boy high school.

So, I had a decision to make: I could distance myself from my friend—or I could become a social outcast.

Let's just say I've never been one to follow the crowd. Not only did I continue to hang out with Robert, I went to Gay Youth Alliance with him. I learned about the community. I made friends. And guess what happened?

AIDS affected me.

This was long before Tom Hanks got the Oscar for

Philadelphia

. This was before anybody famous had died from "pneumonia." But I got to know a guy at GYA. He was cool, a good guy—and he got sick.

And then the priest who taught French at my oh-so-Catholic high school got sick.

The disease that wasn't going to affect me was killing people I knew. People I liked. So, I started educating myself about it.

By the time my favorite basketball player announced he was HIV-positive, I had long since shed my ignorance. I knew the hype about it being "just" a homosexual disease, as if that somehow mitigated its severity, was fallacious. I knew about Haiti, Europe, and Africa. I knew about the growing diversity of the afflicted in the United States.

In the eighties and early nineties, AIDS awareness was everywhere. You didn't just call it HIV, because everyone who got HIV at that time eventually got AIDS. It was a sexually transmitted death sentence. The moral indignation of the Reagan years kept it isolated in the minds of middle America for awhile. Made it something that misguided and hateful individuals marginalized by blaming it on a single demographic.

But when a cousin or a favorite uncle or a sister dies, things tend to come out of the margins. The fight was a popular one.

And The Band Played On

—and later,

Rent

—made headlines and money. David Ho was honored as

Time Magazine

's 1996 Man of the Year for his pioneering work with protease inhibitors.

By the end of the nineties, however, AIDS wasn't in the headlines anymore. As safe sex campaigns began to stem the spread of the disease and education decreased the mystery, the anxiety and fear also lessened. As people learned that it was possible to live with HIV, it looked less like a science-fiction disease that would end the world. As the diagnosed population became broader than the gay community, it became less controversial. People were no longer glued to their television sets for each celebrity announcement or research breakthrough. So, the evening news bumped stories about the disease deeper into the broadcast—and eventually off the air altogether. Newspapers buried stories in the back pages.

AIDS and HIV just kind of faded away, right? Wrong! The United Nations agency UNAIDS estimated that at the end of 1999, 33 million people were living with HIV, and an estimated 2.6 million died that year, the highest numbers since the beginning of the epidemic.

Yet, studies of U.S. media coverage of the AIDS epidemic showed that the number of news stories related to the disease had peaked a dozen years earlier in 1987, with slight bumps following Magic Johnson's 1991 announcement and the introduction of combination therapies in 1996 and 1997.

Today, we hear less about AIDS and HIV in the news than perhaps ever before. This is despite HIV having become one of the United States' top three disease-related killers of young adults. Despite there still being more than 40,000 new cases annually in the U.S. alone. According for the Centers for Disease Control, HIV/AIDS is the leading cause of death for young African-American women in the United States.

The leading cause of death.

That certainly puts the final nail in the coffin of the old "gay plague" argument, doesn't it? By the end of this year, more than a million Americans will be living with HIV.

More than 22 million people worldwide have died from AIDS. That's over two and a half times the number killed in World War I. AIDS is a preventable disease that's been deadlier than three hundred seventy-eight Vietnam wars.

The need is great. But with the lack of reinforcement by the media, much of the public doesn’t see HIV as a problem anymore.

Those who have contributed to this volume of Coming Together have not been lulled into complacency. Here you will find a diverse and talented group. Just as HIV is not exclusive to any single demographic, the work in this book embraces all areas of our lives. Naturally, it contains stories about same-sex relationships. But there are also stories about hope. About loss. About love. About the effects of disease in general, not just AIDS. But no matter how diverse the contents, they all share one thing.

The writers, the editor, and the publisher have each made a commitment—not only to donate all their proceeds to AVERT, but to pursue the goal of keeping this horrible epidemic where it belongs: in the forefront of our minds and hearts until there is a cure.

Will Belegon

April 2008

©

www.willbelegon.com