Coming of Age in the Milky Way (11 page)

Read Coming of Age in the Milky Way Online

Authors: Timothy Ferris

Tags: #Science, #Philosophy, #Space and time, #Cosmology, #Science - History, #Astronomy, #Metaphysics, #History

Now everything worked. Kepler had arrived at a fully realized Copernican system, focused on the sun and unencumbered by epicycles or crystalline spheres. (In retrospect one could see that Ptolemy’s eccentrics had been but attempts to make circles behave like ellipses.)

Fabricius replied that he found Kepler’s theory “absurd,” in that it abandoned the circles whose symmetry alone seemed worthy of the heavens. Kepler was unperturbed; he had found a still deeper and subtler symmetry, in the

motions

of the planets. “I discovered among the celestial movements the full nature of harmony,” he exclaimed, in his book

The Harmonies of the World

, published eighteen years after Tycho’s death.

I am free to give myself up to the sacred madness, I am free to taunt mortals with the frank confession that I am stealing the golden vessels of the Egyptians, in order to build of them a temple for my God, far from the territory of Egypt. If you pardon me, I shall rejoice; if you are enraged, I shall bear up. The die is cast.

35

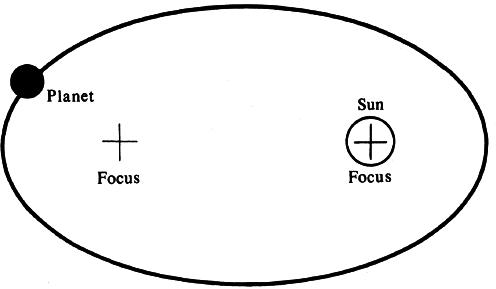

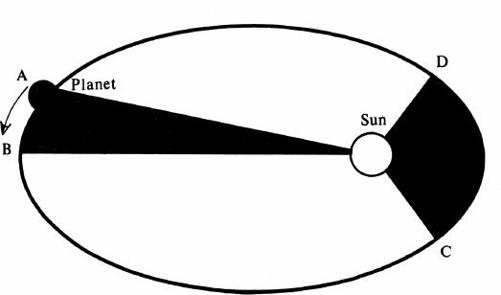

And so on. The cause of his celebration was his discovery of what are known today as Kepler’s laws. The first contained the news he had communicated to Fabricius—that each planet orbits the sun in an ellipse with the sun at one of its two foci. The second law revealed something even more astonishing, a Bach fugue in the sky. Kepler found that while a planet’s velocity changes during its year, so that it moves more rapidly when close to the sun and more

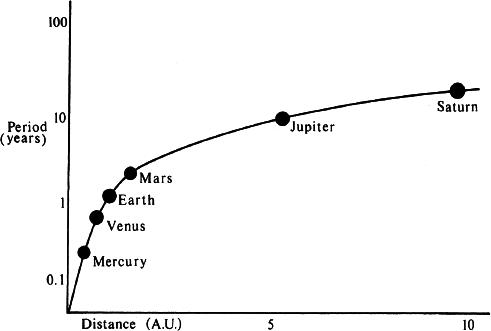

slowly when distant from the sun, its motion obeys a simple mathematical rule: Each planet sweeps out equal areas in equal times. The third law came ten years later. It stated that the cube of the mean distance of each planet from the sun is proportional to the square of the time it takes to complete one orbit. Archimedes would have liked that one. Newton was to employ it in formulating his law of universal gravitation.

Kepler’s first law: The orbit of each planet describes an ellipse, with the sun at one of its foci.

Kepler’s second law: If time

AB

= time

CD

, area

ABSun

= area

CDSun.

Kepler’s third law: The cube of the distance of each planet from the sun is proportional to the square of its orbital period.

Here at last was “the principal thing” of which Copernicus had dreamed, the naked kinematics of the sun and its planets. “I contemplate its beauty with incredible and ravishing delight,” Kepler wrote.

36

Scientists have been contemplating it ever since, and Kepler’s laws today are utilized in studying everything from binary star systems to the orbits of galaxies across clusters of galaxies. The intricate etchings of Saturn’s rings, photographed by the Twin Voyager spacecraft in 1980 and 1981, offer a gaudy display of Keplerian harmonies, and the Voyager phonograph record, carried aboard the spacecraft as an artifact of human civilization, includes a set of computer-generated tones representing the relative velocities of the planets—the music of the spheres made audible at last.

But the sun of learning is paired with a dark star, and Kepler’s

life remained as vexed with tumult as his thoughts were suffused with harmony. His friend David Fabricius was murdered. Smallpox carried by soldiers fighting the Thirty Years’ War killed his favorite son, Friedrich, at age six. Kepler’s wife grew despondent —“numbed,” he said, “by the horrors committed by the soldiers”—and died soon thereafter, of typhus.

37

His mother was threatened with torture and was barely acquitted of witchcraft (due, the court records noted, to the “unfortunate” intervention of her son the imperial mathematician as attorney for the defense) and died six months after her release from prison. “Let us despise the barbaric neighings which echo through these noble lands,” Kepler wrote, “and awaken our understanding and longing for the harmonies.”

38

He moved his dwindling family to Sagan, an outback. “I am a guest and a stranger here. … I feel confined by loneliness,” he wrote.

39

There he annotated his

Somnium

, a dream of a trip to the moon. In it he describes looking back from the moon to discern the continent of Africa, which, he thought, resembled a severed head, and Europe, which looked like a girl bending down to kiss that head. The moon itself was divided between bright days and cold dark nights, like Earth a world half darkness and half light.

Dismissed from his last official post, as astrologer to Duke Albrecht von Wallenstein, Kepler left Sagan, alone, on horseback, searching for funds to feed his children. The roads were full of wandering prophets declaring that the end of the world was at hand. Kepler arrived in Ratisbon, hoping to collect some fraction of the twelve thousand florins owed him by the emperor. There he fell ill with a fever and died, on November IS, 1630, at the age of forty-eight. On his deathbed, it was reported, he “did not talk, but pointed his index finger now at his head, now at the sky above him.”

40

His epitaph was of his own composition:

Mensus eram coelos, nunc terrae metior umbras

Mens coelestis erat, corporis umbra iacet.I measured the skies, now I measure the shadows

Skybound was the mind, the body rests in the earth.

The grave has vanished, trampled under in the war.

*

One could write a plausible intellectual history in which the decline of sun worship, the religion abandoned by the Roman emperor Constantine when he converted to Christianity, was said to have produced the Dark Ages, while its subsequent resurrection gave rise to the Renaissance.

*

Modern myth to the contrary, little of the ecclesiastical opposition to Copernicanism appears to have derived from fear that the theory would “dethrone” humanity from a privileged position at the center of the universe. The center of the universe in Christian cosmology was hell, and few mortals would have felt dis-accommodated at being informed that they did not live there. Heaven was the place of distinction, for Christian and pagan thinkers alike. As Aristotle put it, “The superior glory of … nature is proportional to its distance from this world of ours.” When Leonardo da Vinci suggested that the earth “is not in the center of the universe,” he intended no slander of Earth, but was suggesting that our planet is due the same dignity—

noblesse

—as are the stars.

*

Comets are chunks of ice and dirt that fall in from the outer solar system, sprouting long, glowing “tails” of vapor and dust blown off by the sun’s heat and by solar wind. The appearance of new comets cannot be predicted even today; they appear to originate in a cloud that lies near the outer reaches of the solar system, about which little is understood. Their orbits, altered by encounters with the planets and by the kick of their own vapor jets, remain difficult to predict as well.

*

The cometary stigma persisted into the early twentieth century, when millions bought patent medicines to protect themselves from the evil effects of comet Halley during its 1910 visitation. Several fatalities were reported, among them a man who died of pneumonia after jumping into a frozen creek to escape the ethereal vapors. A deputation of sheriffs intervened to prevent the sacrifice of a virgin, in Oklahoma, by a sect called the Sacred Followers who were out to appease the comet god.

*

Twentieth-century radio astronomers using Renaissance star charts have located the wreckage of both Tycho’s supernova, now designated 3C 10 in the Cambridge catalog of radio sources, and of Kepler’s, known as 3C 358. Also located is the remnant of the Vela supernova, which blazed forth in the southern skies some six to eight

thousand

years ago, casting long shadows across the plains of Eden. (The word

Eden

is Sumerian for “flatland,” and is thought to refer to the fertile, rock-free plains of the Tigris-Euphrates.) The Sumerians identified that supernova with the god Ea (in Egypt, Seshat), whom they credited with the invention of writing and agriculture. The Ea myth thus suggests that the creation of agriculture and the written word were attributed by the ancients to the incentive provided by the sight of an exploding star.

T

HE

W

ORLD IN

R

ETROGRADE

Pure logical thinking cannot yield us any knowledge of the empirical world; all knowledge of reality starts from experience and ends in it…. Because Galileo saw this, and particularly because he drummed it into the scientific world, he is the father of modern physics—indeed, of modern science altogether.

—Einstein

What if the Sun

Be Center to the World, and …

The Planet Earth, so stedfast though she seem,

Insensibly three different Motions move?—Milton,

Paradise Lost

H

istory plays on the great the trick of calcifying them into symbols; their legend becomes like the big house on the hill, whose owner is much talked about but seldom seen. For no scientist has this been more true than for Galileo Galilei. Galileo dropping a cannonball and a musket ball from atop the Leaning

Tower of Pisa, thus demonstrating that objects of unequal weight fall at the same rate of acceleration, has come to symbolize the growing importance of observation and experiment in the Renaissance. Galileo fashioning the first telescope symbolizes the importance of technology in opening human eyes to nature on the large scale. Galileo on his knees before the Inquisition symbolizes the conflict between science and religion.

Such mental snapshots, though useful as cultural mnemonic devices, extract their price in accuracy. The story of Galileo at the Leaning Tower is almost certainly apocryphal. It appears in a romantic biography written by his student Vincenzio Viciani, but Galileo himself makes no mention of it, and in any event the experiment would not have worked: Owing to air resistance, the heavier object would have hit the ground first. Nor did Galileo invent the telescope, though he improved it, and applied it to astronomy. And, while Galileo was indeed persecuted by the Roman Catholic Church, and on trumped-up charges at that, he did as much as anyone outside of a few hard-core Vatican extremists to lay his body across the tracks of martyrdom.

Still, these distortions in the popular conception of Galileo work to his favor, and that would have pleased him. A devoted careerist with a genius for public relations, he was ahead of his time in more ways than one. His mission, as he put it, was “to win some fame.”

1